The study, published January 8 in the peer-reviewed scientific journal PLOS ONE, presents "sobering results" of a survey that took six years and covered 11 countries.

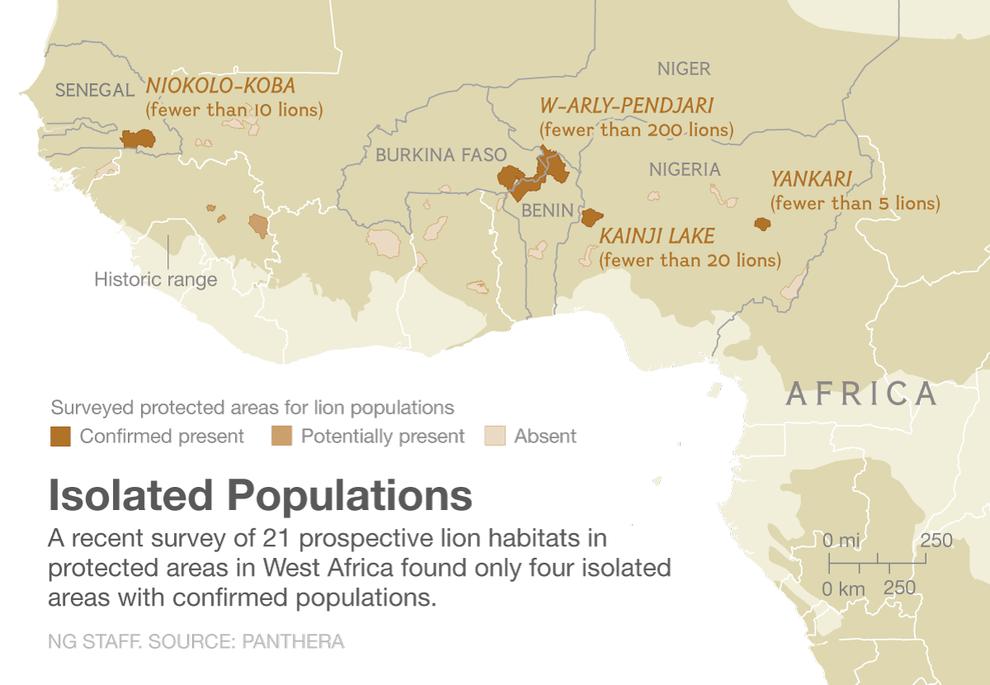

Lions once ranged from Senegal to Nigeria, a distance of more than 1,500 miles. The new survey found an estimated total of only 250 adult lions occupying less than one percent of that historic range. The lions form four isolated populations: one in Senegal; two in Nigeria; and a fourth on the borders of Benin, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Only that last population has more than 50 lions.

"It was really not known that the status of the lion was so dire in West Africa," study co-author Philipp Henschel, the Gabon-based survey coordinator for the big cat conservation group Panthera, told National Geographic. "In many countries it was not known that there were no more lions in those areas because there had been no funding to conduct surveys."

Henschel and his colleagues built on previous work by Duke University researchers, which like the new survey received funding from National Geographic's Big Cats Initiative. The new survey covered 21 protected areas in 11 countries in West Africa.

"All of these still contain suitable, intact lion habitat, and we thought all would contain lions," said Henschel. "But instead we found only four isolated and severely imperiled populations."

A Separate Subspecies?

The taxonomy of the West African lion is currently being reviewed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), based on recent genetic studies that suggest it may be a distinct subspecies from the more familiar lions of southern and eastern Africa, which are thought to number less than 35,000. Henschel said he supports the naming of a new subspecies. It would most likely be designated as "critically endangered," which would encourage more international support for conservation efforts, he said.

West African lions are lighter in build than the ones in East and South Africa. They appear to have longer legs, and the males have thinner manes.

"Lions in West Africa are genetically more different from lions in East and Southern Africa than Siberian tigers are from Indian tigers," said Hans de Iongh, a lion researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands who did not participate in the new study. West African lions appear to be more similar to the extinct "Barbary lions" that once roamed North Africa, and to the last Asiatic lions surviving in India, said Henschel.

West African lions also tend to form much smaller prides. "In East and South Africa, you can have prides of up to 40 individuals, but in West Africa prides are usually one male, one to two females, and their dependent offspring," said Henschel.

West Africa is more heavily forested than other parts of the continent. Historically, lions did penetrate into the dense woods, but in recent years they have been largely confined to more open woodlands and savannah-like lands in protected areas. Overall, the soils are poorer and prey is less abundant in the west, "which probably explains the lower pride sizes," Henschel said.

Threats to the West African Lion

The lion's historic range in West Africa was drastically reduced by large-scale land use changes, Henschel said. As people planted farms, cut down trees, and hunted wildlife, the big cats had few places to go. The small islands of protected parks became their only hope.

But in the past few years, lions in those parks have been killed by local people in retaliation for killing some of their livestock. An even bigger problem, Henschel said, is poaching of the lions' prey to supply local bushmeat markets. With the economy in the region depressed and fish stocks off the coast depleted, hungry people have increasingly turned to hunting animals in protected areas.

"Bushmeat has become so valuable that it is becoming international," Henschel said. "In Burkina Faso we saw poachers coming from Nigeria, 100 miles [160 kilometers] away, to shoot big animals and carry them across the border in pickup trucks."

Parks in West Africa have simply not had the resources to prevent retaliatory killings or poaching, said Henschel. "When we looked at the 21 management areas, we realized that six of them had no operating budget at all, and compared to the big game parks in South and East Africa, they are all understaffed. These 'paper parks' are systematically being stripped by poachers."

De Iongh, who has studied West African lions for more than 20 years but has not yet reviewed the new paper, said, "I can confirm that the situation is very bleak. This region has been neglected by the conservation world for many years and only in recent years have some conservation funds become available."

Can West African Lions Be Saved?

The fate of the lion in West Africa will be decided "in the next five years, or maybe even less," said Henschel. "If we can find sufficient funding, in cooperation with national authorities and the international community, then I think there is hope. There are committed individuals on the ground, but they lack funding."

Henschel said the secret to long-term success will be supplementing conservation dollars with an alternative revenue stream, such as the nature-based tourism that pumps billions of dollars into South and East Africa every year. West Africa has not gotten much tourism in the past, Henschel said, and "West African governments have been reluctant to invest in their protected areas because they cannot be sure of short-term returns."

De Iongh added, "I think the way forward is to enhance education programs and to train local guards."

"West African lions have unique genetic sequences not found in any other lions, including in zoos or captivity," Christine Breitenmoser, co-chair of the IUCN/SCC Cat Specialist Group, said in a statement. "If we lose the lion in West Africa, we will lose a unique, locally adapted population found nowhere else. It makes their conservation even more urgent."

Henschel said he is cautiously optimistic. Perhaps the World Bank, foreign governments, or other international agencies will be inspired to help the region develop an infrastructure for responsible tourism, he suggested.

"In the Russian Far East, Siberian tigers are now doing better with all the money invested, because everyone knows about the status of the tiger," Henschel said. "We hope to create similar projects in West Africa."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter