- The Red Lady of Paviland is actually the skeleton of a man and got its name as it was dyed in red ochre, giving its bones the unusual colour

- It is the oldest ceremonial burial of a human discovered in Western Europe

- Byron Davies, the Assembly Member for South Wales, has asked Oxford University to return the remains of the man who was buried in Gower

The university is currently the custodian of a 33,000-year-old skeleton that received the oldest ceremonial burial in Western Europe.

But Byron Davies, the Assembly Member for South Wales, has asked the university to return the remains of the person known as the Red Lady of Paviland, who was buried in Gower, Wales.

It was discovered in a limestone cave in Gower in 1823 by a geology professor at the university, which is why the skeleton has been under lock and key in Oxford ever since.

It is still the oldest ceremonial burial of a human discovered in Western Europe.

Oxford University said the skeleton is one of the iconic relics of the British Palaeolithic, and a cast of the skeleton is on permanent display, along with related artefacts, at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

WHO WAS THE RED LADY OF PAVILAND?

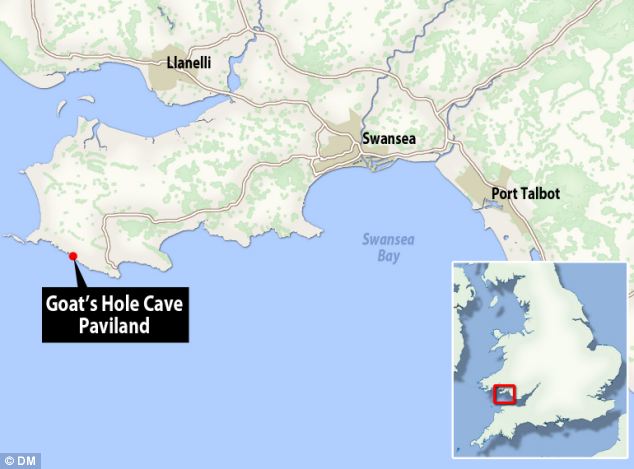

- The skeleton was found during at Goat's Hole Cave; one of the limestone caves between Port Eynon and Rhossili, on the Gower Peninsula, south Wales.

- When Reverend William Buckland first discovered the skeleton in 1823, he misjudged both its age and its sex.

- As a creationist, he believed no human remains could have been older than the Biblical Great Flood and wildly underestimated the skeleton's true age, believing the remains to date back to the Roman era.

- Reverend Buckland believed the skeleton was female in large part because it was discovered with decorative items, including perforated seashell necklaces and jewellery thought to be of elephant ivory but now known to be carved from the tusk of a mammoth.

- These decorative items combined with the skeleton's red dye caused Buckland to mistakenly speculate that the remains belonged to a Roman prostitute or witch.

- These decorative items combined with the skeleton's red dye caused Buckland to mistakenly speculate that the remains belonged to a Roman prostitute or witch.

- Bone protein analysis indicates that the 'lady' lived on a diet that consisted of between 15 per cent and 20 per cent fish, which, together with the distance from the sea (as the cave was located 70 miles inland some 33,000 years ago,) suggests that the people may have been semi-nomadic, or that the tribe transported the body from a coastal region for burial.

Mr Davies believes the skeleton 'belongs to Gower' and said: 'It would be good to have it back where it belongs. It adds to the bigger picture of bringing people to the city and to the Gower.'

'I understand the University of Oxford is not in favour of releasing it, so there would have to be some negotiation.'

'But the university has it at the moment and it is not on display with them, which I think is wrong,' he said.

He is 'serious' about raising funds to ensure the remains could be kept safe in Swansea, close to where they found and the Red Lady of Peviland was laid to rest.

Mr Davies said: 'I have yet to take the next step which would be to make some sort of contact with the university, to talk to them nicely about it and try to be reasonable.

'They did lend the original bones to the Museum of Wales in, I think, 2009,' he added.

The politician said Swansea Museum if keen to look after the Red Lady, but noted that the outcome is 'up to the university'.

'I have a fairly persuasive tongue in me. I hope I've a chance,' he said.

This week, UK Culture Secretary Maria Miller, who was brought up in Bridgend, spoke with Mr Davies about getting the bones back.

'When she came down she was quite fascinated by the story and agreed it should be on display in Swansea,' Mr Davies said.

However, a spokesman from Oxford University said the skeleton is 'held securely in a collections room inside the museum and is available for researchers and guided tours'.'

'The question of whether the "Red Lady" should be repatriated to a permanent home in Wales is not currently under consideration," he said.

A cast is on display in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and in 2014 the bones will go on display at London's Natural History Museum.

HOW OLD IS THE RED LADY OF PAVILAND?

- In the mid 19th Century, researchers discovered the skeleton dated from a Palaeolithic age.

- Several attempts have been made at radiocarbon dating the 'Red Lady' and associated artefacts.

- Most recent suggests that it is, by a significant margin, the oldest of a group of 'rich', Mid-Upper Palaeolithic burials in Western Europe, dating to between 34,050 and 33,260 years old.

- Most recent suggests that it is, by a significant margin, the oldest of a group of 'rich', Mid-Upper Palaeolithic burials in Western Europe, dating to between 34,050 and 33,260 years old.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter