The transition from hunting and gathering to farming was one of the most momentous upheavals in human prehistory. That transition marks the beginning of the Neolithic period, which started nearly 11,000 years ago, when people of the Near East domesticated plants and animals and settled down in sedentary communities with permanent houses. In Europe, meanwhile, roving foragers of so-called Mesolithic cultures continued to hunt, fish, and gather wild plants. The Neolithic apparently first spread from Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) to Greece and the Balkan region sometime after 8500 years ago. Researchers have long debated what happened when foragers and farmers came face to face. Did they make war, make peace, or simply ignore each other?

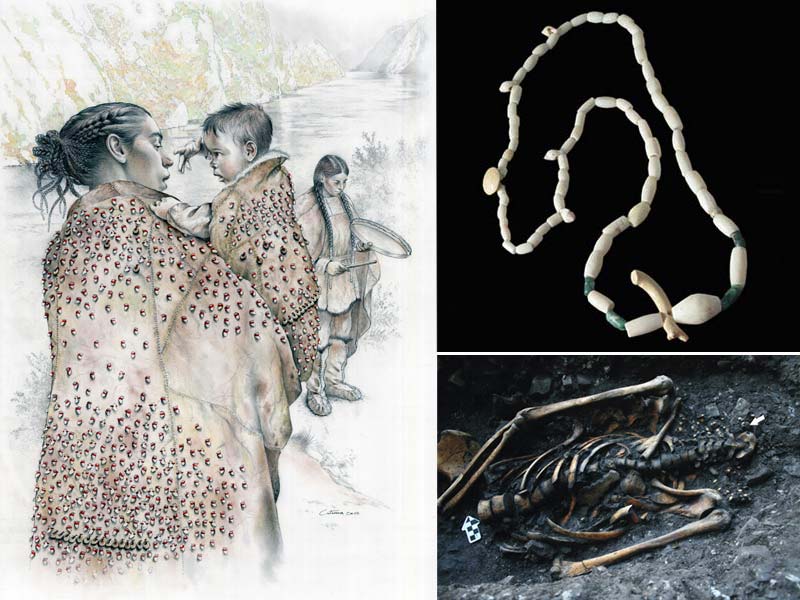

Sites in the Balkans offer a rare glimpse of the tumultuous time when farmers began to arrive with their new way of life. Since the 1960s, archaeologists have excavated more than 500 skeletons spanning the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods from dozens of sites along the Danube River gorges on the border between Romania and Serbia. Mesolithic peoples were still fishing abundant sturgeon and other river fish and maintaining long-distance relations with other hunter-gatherers, as evidenced by necklaces made from marine shells from the distant Black Sea. But distinct Neolithic-style personal ornaments and architecture also turn up in late Mesolithic sites such as Lepenski Vir in Serbia, a large settlement rich in burials and art such as boulders sculpted with half-human, half-fish images.

To zero in on the possible cultural interaction, archaeologists Dušan Borić of Cardiff University in the United Kingdom and T. Douglas Price of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, analyzed ratios of isotopes of strontium in the teeth of 153 skeletons from nine sites at the Danube gorges. The skeletons were dated from 13,500 to 7500 years ago, or from just before the Mesolithic to the early Neolithic. The ratio of the isotopes of strontium-87 and strontium-86 varies widely in different soils and rocks, and ingested strontium collects in the teeth of children, providing a lifelong signature of where a person grew up. By comparing strontium ratios in teeth with those of the local environment, researchers can distinguish between people who grew up in a particular area and immigrants who grew up somewhere else.

Borić and Price analyzed skeletons whose age had been directly determined by radiocarbon dating and spotted a significant change in the strontium profile right around the time that the first signs of Neolithic culture show up, as they report online this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The strontium ratios of Mesolithic peoples along the Danube reflected the river sediments on which they lived. But at 8200 years ago, skeletons with ratios both significantly higher and lower than this appear. These skeletons show up even at sites that still appear to be primarily Mesolithic in their culture. The "nonlocal" individuals appear to come from regions far from the river, and the number of immigrants jumps over time. Before 8200 years ago, for example, almost all of the burials at Lepenski Vir were of locals. But five of 19 people buried there between 8200 and 7950 years ago were nonlocals - and all were women.

Borić and Price conclude that the nonlocals represent Neolithic migrants. The ratio of nitrogen isotopes in their teeth and bones, which reflects a person's diet, bolsters that idea. Nonlocals tended to have a nitrogen ratio typical of a terrestrial rather than aquatic diet, as would be expected in farmers who were not eating fish. The mixing of Mesolithic and Neolithic burials suggests that the two groups lived side by side for at least 200 years until the Neolithic completely supplanted the Mesolithic culture, Borić and Price conclude. "The forager communities were being integrated into the Neolithic social networks rather than resisting them," Borić says. "The picture is largely one of peaceful coexistence."

Archaeologist Alex Bentley of the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom calls the study a "great paper." He adds that the evidence that Neolithic women were migrating into Mesolithic communities is "fascinating," because previous genetic studies had suggested that the opposite happened as farming spread further west into Europe - that is, that hunter-gatherer gals entered Neolithic communities and mated with farmer guys.

Indeed, Ron Pinhasi, an archaeologist at University College Dublin, cautions that the scenario in the Danube gorges might not represent a model for all of Europe during the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition. "I see these populations as an isolated case," Pinhasi says, rather than a typical example of forager-farmer interactions.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter