Carol Patterson was waiting for a call from her doctor. When the phone rang on that afternoon in August 2011 at her home in Cortland, Ohio, it wasn't a physician on the other end. A woman named Robin said she was representing the American Diabetes Association.

Robin didn't ask for money. She asked Patterson to stamp and mail pre-printed fundraising letters to 15 neighbors. Both of Patterson's parents and one grandmother had been diabetic, so she agreed to do it, Bloomberg Markets magazine reports in its October issue.

"I thought since it does run in the family, it wouldn't hurt for me to help," says Patterson, 64, a retired elementary school teacher. She guessed, based on what she knew about charity fundraising, that about 70 to 80 percent of the money she brought in would be used for diabetes research.

The truth was almost the exact opposite. The vast majority of funds Patterson, her neighbors and people like them throughout the country would raise -- almost 80 percent -- would never be made available to the Diabetes Association. Instead, that money collected from letters sent to neighbors would go to the company that employed Robin and an army of other paid telephone solicitors: InfoCision Management Corp.

Just 22 percent of the funds the association raised in 2011 from the nationwide neighbor-to-neighbor program went to the charity, according to a report on its national fundraising that InfoCision filed with North Carolina regulators.

'Terribly Wrong'

And it gets worse. Many of the biggest-name charities in the U.S. have signed similarly one-sided contracts with telemarketers during the past decade. The American Cancer Society, the largest health charity in the U.S., enlisted InfoCision from 1999 to 2011 to raise money.

In fiscal 2010, InfoCision gathered $5.3 million for the society. Hundreds of thousands of volunteers took part, but none of that money -- not one penny -- went to fund cancer research or help patients, according to the society's filing with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service and the state of Maine.

Fees Added

Every bit of it went to InfoCision, the filings say. The society actually lost money on the program that year, according to its filings. InfoCision got to keep 100 percent of the funds it raised, plus $113,006 in fees from the society, government filings show.

Major charities compound the deception by encouraging telephone solicitors to lie. InfoCision scripts approved by both the Diabetes Association and the Cancer Society for what the telemarketer calls neighbor-to-neighbor campaigns in 2010 instruct solicitors to say, when asked, that at least 70 percent of the money raised will be used for charitable purposes.

Yet in contracts with InfoCision in that very same year, the association and society said they expected that the telemarketing firm would keep more than 50 percent of all the funds it collected.

Altogether, more than 5 million Americans volunteered to raise money for these two groups -- and other charities that hired InfoCision -- from their neighbors since 2005 after being pitched by solicitors using charity-approved scripts, according to state regulatory filings.

'False Pretenses'

"If that's what they do systematically, then they're obtaining money under false pretenses," he says. "I don't just think it's incredible. I'd be surprised if it isn't criminal."

Naomi Levine, chair and executive director of the George H. Heyman Jr. Center for Philanthropy and Fundraising at New York University, says charities are knowingly being dishonest.

"I'm amazed at that," she says. "I didn't know about it. It's deceitful." Levine, 89, was a nonprofit fundraiser for three decades, bringing in more than $2 billion for NYU.

"Even for them to engage in a program like that is shocking to me," she says. "And I'm in the field. So how can you expect donors to know that?"

Richard Erb, vice president of membership and direct marketing at the Alexandria, Virginia-based Diabetes Association, defends his group's practices.

'A Dime'

"If we came into it and said, 'Geez, I'm not going to make a dime on this,' do you think we would have anyone who would give us money?"

Greg Donaldson, a senior vice president at the Atlanta- based Cancer Society likens telemarketing campaigns that net the charity low percentages of donations to retailers pricing a product below cost to lure shoppers.

"It's certainly not inconsistent for organizations like ours to invest in some loss-leader strategies, to engage people in long-term meaningful relationships," he says.

In the past decade, many of the nation's biggest health charities have hired InfoCision, including the American Heart Association, American Lung Association, American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, March of Dimes Foundation and National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Overall, InfoCision brought in a total of $424.5 million for more than 30 nonprofits from 2007 to 2010, keeping $220.6 million, or 52 percent, according to state-filed records.

Evangelical Preachers

InfoCision, which is based in Bath Township, Ohio, near Akron, says on its website that it raises more money for nonprofits than any other telemarketer in the world. The privately held company was founded by Gary Taylor, who got his start raising money for evangelical preachers.

InfoCision, which isn't required to and doesn't disclose revenue or profit, also does marketing for corporate clients such as Time Warner Cable Inc. (TWC) and Verizon Communications Inc. (VZ) The company has a political operation as well.

It did fundraising for Citizens United, the conservative group best known as the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case that allowed unlimited independent spending by corporations and unions on behalf of political candidates. From 2009 to 2011, InfoCision raised $14.7 million for Citizens United.

The telemarketer was as stingy with Citizens United as it was with some of the charities: It kept $12.4 million, or 84 percent, of the money it raised for Citizens United, according to InfoCision filings with North Carolina. InfoCision has also worked for the National Republican Congressional Committee.

$115 Million

The group paid InfoCision more than $115 million to raise money from 2003 to 2012, according to company filings with the Federal Election Commission. The filings don't say how much InfoCision raised for the committee.

The company's website tells prospective solicitors, "As part of our political call center, you'll help raise funds for political leaders and spread the word about conservative causes."

InfoCision has barely been touched by legal trouble over its fundraising for charities. The Ohio Attorney General's Office, after listening to recordings of phone calls by InfoCision solicitors, negotiated a settlement with the company, filed in civil court in April.

Ohio said InfoCision's employees had misled people by giving them false information about how much of their contributions would actually go to charities. While denying that it had done anything wrong, InfoCision promised not to mislead potential future donors.

Case Settled

The company agreed to pay $75,000 to settle the case -- an amount equal to less than one-10th of 1 percent of its revenue from charity fundraising from 2007 to 2010.

Big charities don't need telemarketers to raise money, yet they continue to use them -- even when it appears to make little economic sense.

Organizations generally get most of their contributions through their own mailings, phone calls, Internet sites and foundation grants. In those appeals, charities can honestly say that about 70 to 80 percent of the money directly serves the cause donors are supporting. The rest covers overhead.

The Diabetes Association says on its website that it invested more than $33.5 million last year in medical research. The group says it offers help to the 24 million people in the U.S. with diabetes.

Tax Deductable

"An impressive 73 percent of every dollar spent supports research, advocacy and services for people affected by diabetes," the website says. "Please make a tax-deductible donation today."

The Cancer Society's website is headlined "The Official Sponsor of Birthdays." The society says it offers support to the 13.7 million Americans with cancer and pays for research and public education about the disease. "Because of supporters like you, people who rely on the American Cancer Society will get the help they need," its website says. "Please donate."

Americans trust charities -- and like giving them money. The U.S. is the most generous country, according to the World Giving Index compiled by Charities Aid Foundation based on Gallup data of 153 nations.

Americans donated $298 billion to charities in 2011, according to the Center on Philanthropy at Indiana University in Indianapolis. And they gave with confidence.

Trusting Charities

When the center and Bank of America Corp. polled households with annual incomes exceeding $200,000 in 2010, 94.5 percent said they trust charities compared with 68.4 percent for corporations and just 31.9 percent for Congress.

Telemarketing companies representing charities know that people more often give with their hearts than with their heads. On its website, InfoCision says:

"Telephone purchases and donations are made on impulse. These are dictated not by reason or logic but by feelings of emotion. We are very familiar with the emotions of fundraising: sympathy, fear, anger, guilt, etc."There's one tactic the InfoCision website doesn't cover: deception. The ruse begins with the name that flashes on your caller ID when a telemarketer is phoning on behalf of a charity. It's the charity's name that often shows up, not that of the telemarketing firm.

The misrepresentation can continue on the call itself. Solicitors in recordings obtained by the Ohio Attorney General's Office sometimes identify themselves to potential donors as "volunteers." They're not; they're paid employees of InfoCision.

Telemarketer Lie

The bigger lie telemarketers tell is what they say about how much money will go to the charities they're working for.

According to documents obtained through an open records request with the Ohio attorney general, the Diabetes Association approved a script for InfoCision telemarketers in 2010 that includes the following line:

"Overall, about 75 percent of every dollar received goes directly to serving people with diabetes and their families, through programs and research."Yet that same year, InfoCision's contract with the association estimated that the charity would keep just 15 percent of the funds the company raised; the rest would go to InfoCision.

Association Vice President Erb offers no apologies for the script, saying the association runs many fundraising campaigns and, overall, about 75 percent of the money goes to its programs. He acknowledges that the contract with InfoCision estimated that the telemarketer would get to keep 85 percent of the funds it raised.

'We're a Business'

Erb also says he isn't happy that volunteers are upset upon learning the truth.

"Obviously, if people feel betrayed or that we're not being honest with them, it doesn't make me feel well," he says. "But the thing is, we're a business. There has never been a time or a place where we said, 'Most of this money is coming to us."'

The Cancer Society, in a Sept. 1, 2009, contract with InfoCision, estimated that the charity would get 44 percent of the amount the company collected in the following fiscal year.

The telemarketer script for the same year approved by the society for InfoCision asks solicitors to say something different:

"Overall, about 70 cents of every dollar received goes to the programs and services that we provide."Donaldson, the society's senior vice president, declined to comment on the contradiction between the contract and the script, saying the society doesn't provide "proprietary competitive information regarding individual programs."

New Donors

Once the charity has the names of new donors, he says, it goes back to those people in the future to request more contributions, without paying a telemarketer, he says.

NYU's Levine scoffs at that explanation. Even if the society increases its future list of donors, it purposely misled and disrespected millions of people who wanted to contribute to medical research, she says. Few would donate again if they were aware the charity had knowingly pushed them to contribute money that would end up in the coffers of a telemarketer.

"I think it's a bunch of baloney," she says. "It's not an honest way to get volunteers involved. Their donors don't really know this is a loss leader. Volunteers are critical to a campaign. But you don't have to use that technique."

A clearer picture of how charities work with telemarketers emerges in the recordings of calls made by InfoCision for the society's Notes to Neighbors program in 2009. Copies of the recordings, gathered by the Ohio Attorney General's Office, were obtained by Bloomberg Markets magazine through an open records request.

Call Recorded

The phone rang at the home of Paul Kolb in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, on Aug. 9, 2009. Kolb's adult son, also named Paul, picked it up.

"Hi, Mr. Kolb?" the caller said. "My name is Stephanie. I'm calling from InfoCision for Ohio division of American Cancer Society."

The rest of the conversation went like this:

Stephanie: "Because of supporting and caring people like you, we've made great strides in our mission to fight cancer and create a world with more birthdays. We're calling today to ask for your help just by mailing 15 letters to your neighbors. All you have to do is address and stamp and mail the letters. OK, Mr. Kolb?"'You Guys'

Kolb: "Yeah. Now, how much of the donation goes to the American Cancer Society?"

Stephanie: "Seventy-eight cents of every dollar."

Kolb: "Does the money go to you guys and then to the American Cancer Society?"As it turned out, the society got less than half of the money raised in that campaign, according to its filings with the IRS and North Carolina. In addition to giving false information about how the donations would be used, the solicitor unknowingly made another mistake.

Stephanie: "No, we only get, like, 22 cents of the dollar. We don't get that much."

Kolb: "I'll look over the material, and if I feel comfortable with it, I can pass it out."

Stephanie: "We need a definite yes or no. We don't want to waste material. We're a very legit company and American Cancer Society is a legit company."

Kolb: "I can't really give you a yes or no over the phone."

Stephanie: "I'm very sorry because the money is going to a good cause."

An Investigator

Paul Kolb Jr. is an investigator for the Ohio Attorney General's Office. That was one reason the state decided to request recordings of calls from InfoCision, including that one.

The society halted its Notes to Neighbors campaign on July 31, 2011, Donaldson says. That came after 360,000 volunteers participated in the program last year.

"The costs have been difficult to defray," says Catherine Mickle, the society's chief financial officer.

Many charities say they see little downside to contracts that allow InfoCision to keep most, or even all, of the money raised.

"We have break-even contracts with these telemarketers so we don't 'lose' money and sometimes we even make a little," says Mike Townsend, spokesman for the American Lung Association.

March of Dimes spokeswoman Michele Kling says, "This cost of fundraising is in line with other large nonprofit health organizations."

'Fairly Effectively'

Kelly Browning, chief executive officer of the American Institute for Cancer Research, says he's happy that his organization has used InfoCision for more than a decade. "They have the kind of scale required to do it and do it fairly efficiently," he says.

InfoCision presents itself to the world in grand fashion. A green sign outside its three-story corporate headquarters in a Bath Township office park proclaims the firm to be "The highest-quality call-center company in the world!"

InfoCision boasts of its high ethical standards.

"The quality and integrity of the people we hire, the way they operate and the services we provide will be second to none in all the industries we serve," the company says on its website.

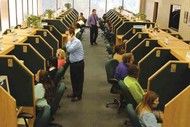

A visit to InfoCision's headquarters shows row after row of mostly middle-aged, headset-wearing telephone solicitors separated by partitions. Many of them earn the minimum wage of $7.40 an hour, according to InfoCision filings with Ohio. InfoCision has more than 4,400 employees in three states and Ontario, Canada, it says.

Gold Trophies

Some telemarketer desks display gold trophies awarded by the company for telemarketing prowess. The solicitors receive on-the-job training in reading scripts, keeping people from hanging up and coaxing time and money out of those who are reluctant.

Job turnover in the industry runs high -- as much as 70 percent a year, says Sally Emch, who founded telemarketing company FutureMarket Telecenter Inc. and ran it for 19 years. Her company raised money for both the Cancer Society and the Diabetes Association.

Solicitors are on the phone almost nonstop for hours, under pressure from their bosses and themselves as they cold-call hundreds of people who routinely resent them from the start, says Emch, who's now retired.

In that kind of stressful environment, telephone solicitors sometimes make mistakes. One InfoCision caller for the Diabetes Association forgot which charity she was representing in the middle of a conversation, according to a recording of the call.

Wrong Charity

During a May 2010 call to Beth Short in Columbus, Ohio, a woman named Carol started by saying she was a "volunteer" for InfoCision calling on behalf of the Diabetes Association.

"Volunteers like you and your husband, John, are the backbone of the American Diabetes Association's effort to save lives," Carol said. She requested that Short send 15 letters to neighbors to raise money. Short asked what the donations would be used for. The ensuing conversation went like this:

Carol: "The money goes toward research to prevent birth defects."Another Mistake

Short: "What group is this for?"

Carol: "The March of Dimes."

Short: "I thought you said it was diabetes."

(Pause) Carol: "I'm so sorry. I am calling for the American Diabetes Association today. I also help the Cancer Society. Gosh, I think I should have gotten a cup of coffee before I sat back down to make this call."

Even though Carol called herself a "volunteer," she wasn't. She was a paid employee of InfoCision. And she unwittingly made another mistake, the same one Stephanie made when she called Paul Kolb. Beth Short happened to be a charities unit supervisor in the Ohio Attorney General's Office.

InfoCision uses a hidden tactic for some charities that could lead to invasions of donors' privacy. An obscure contract provision allows InfoCision to force clients such as the Diabetes Association to rent out the names of their donors to other charities -- if InfoCision doesn't receive full payment on a contract.

Asked about this provision, Erb, the Diabetes Association vice president, says he has to go back and read it. As he does, he expresses concern.

"It's not a great clause," he says.

InfoCision founder Taylor, whose company has received so much money from charities, is himself a benefactor. In 2004, he donated $3.5 million to start the Taylor Institute for Direct Marketing at the University of Akron, his alma mater.

InfoCision Stadium

The university's InfoCision Call Center is a 12-seat room where students learn to make telemarketing calls. In 2007, Taylor paid $10 million for naming rights to the university's InfoCision Stadium.

Taylor began his fundraising career in the 1970s, working for the late televangelist Rex Humbard. Taylor started InfoCision in his house in 1982 to raise money for religious groups. The company's website says that solicitors at its religion division sometimes pray with callers as the firm seeks donations.

InfoCision is a family affair. Taylor, 59, who suffered a heart attack in 2009 a day after the InfoCision Stadium dedication ceremony, stepped down as CEO in 2004. His wife, Karen, 57, is chairman; his son, Craig, 27, is executive vice president; and his daughter, Lindsay, 30, is assistant secretary.

Golf Courses

Taylor and Karen live on a 28-acre (11-hectare) wooded estate in Akron. In addition to InfoCision, he owns three golf courses and a marketing company.

Taylor was an outspoken opponent of efforts by the Federal Trade Commission in 2003 to begin the National Do Not Call Registry, allowing people to block calls from for-profit solicitors. In an interview with Customer Interaction Solutions, a trade journal, he said:

"The most pressing issue, without a doubt, is excessive governmental regulation. It seems that the politicians and regulators are ignoring the significant benefits we provide through job creation, economic growth and the goods and services we cost-effectively market for our clients."

InfoCision Chief of Staff Steve Brubaker says his company is vital to the success of charity fundraising. Many nonprofits have stayed with InfoCision for more than 20 years, proving the firm offers value and integrity, he says.

'High Level'

"We've developed that high level of trust by being good stewards of their money and mission," he says. Campaigns to develop new donors are more expensive than those seeking money from previous supporters, he says. He declined to answer specific questions, saying such information is proprietary to the company or its clients.

He turned down a request for interviews with Taylor and InfoCision executives.

Charities should never agree to one-sided contracts with telemarketers, says Ken Berger, who runs Glen Rock, New Jersey- based Charity Navigator, the nation's largest nonprofit watchdog group.

Berger, who was an executive for 30 years at Volunteers of America, Homeless Solutions and other nonprofits before starting his group, says that charities use telemarketing arrangements as just one more way to gain some money, however small the percentage of donations they receive.

"These organizations were created to provide public benefit," he says. "The fact that the vast majority of money is instead lining the pockets of telemarketers defies the whole reason behind the very creation of these charities."

Hiding Expenses

The nonprofits have become adept at hiding the money they spend on telemarketing firms. An examination of hundreds of annual filings that nonprofits are required to submit to the IRS shows how charities can bury, and sometimes omit, their expenditures on telemarketing.

In state filings, by contrast, charities and telemarketers are required to explicitly say how much is raised by the contractors and who gets the money. Those numbers can be more telling than the IRS filings.

It's an InfoCision filing with North Carolina that reveals that the Diabetes Association got just 22 percent of the money raised nationally by volunteers recruited by the telemarketer in 2011. That figure isn't found in any public filing with the IRS.

Charity reports to governments can be contradictory and confusing. In fiscal 2010, the entire $5.3 million raised in the name of the Cancer Society by InfoCision, along with additional fees, went to the telemarketer, according to filings by the charity with both the IRS and the state of Maine.

Different Numbers

Those dollar amounts and percentages conflict with an InfoCision filing with Ohio for the same period. That report says InfoCision kept 73 percent, or $5.65 million, of $7.77 million in fiscal 2010.

The society's Donaldson says his group didn't pay more to InfoCision than that firm raised, as it reports to the IRS and Maine.

"I can state definitively that the American Cancer Society's Notes to Neighbors program was indeed profitable for the society and never revenue negative," he says.

The IRS reporting requirements skewed the society's reports to the IRS and the Maine filing didn't include all of the charity's Notes to Neighbors revenue, he says. He declined to provide any additional dollar amounts.

"We consider that to be competitively proprietary," Donaldson says.

'You'd Be Pissed'

It's no surprise that telemarketers are wrong when they tell people where donation money would go, says Emch, the founder of FutureMarket. She says the industry standard is that donors are kept in the dark about contracts with charities.

"Would it work for you to know that only 25 or 30 cents of your dollar was going to the organization?" she asks. "No. You'd be pissed. They wouldn't contribute anymore if they knew the truth." Emch closed Corpus Christi, Texas-based FutureMarket in 2010.

Regulators haven't done much to curb telemarketer practices. InfoCision's $75,000 settlement with Ohio was its largest penalty. The company has settled civil complaints of violating fundraising laws in six other states since 2009, paying fines and costs totaling $14,250 -- sanctions that are meaningless in monetary terms for a company of its size.

No less an authority than the U.S. Supreme Court has weighed in on what telemarketers working for charities can say to potential donors. While telephone solicitors have no obligation to volunteer what the firm's cut is of each donation, they don't have a constitutional right to lie, the court ruled in a 2003 Illinois case.

'Misleading Representations'

"States may maintain fraud actions when fundraisers make false or misleading representations designed to deceive donors about how their donations will be used," the court said.

Sometimes charities using telemarketers end up hurting the very people they say they're trying to help.

Beth Rutledge's phone rang in her Clayton, California, home in February 2009. The voice at the other end, an InfoCision solicitor, was filled with urgency on behalf of the American Institute for Cancer Research, according to the recorded call.

The Washington-based Institute provides people with information about how to prevent cancer, it says on its website. Rutledge, 50, was suffering with breast cancer at the time. This is how the call went:

Solicitor: "Since there will be over 1 million new cases of cancer this year alone, we desperately need your help to mail out the 15 pre-printed letters."

'So Overextended'

Rutledge: "I'm just so overextended with volunteer work right now. I can't take this on. It's too overwhelming for me."

Solicitor: "I certainly do realize that your time is valuable and you're very busy. By volunteering a half-hour of your time, you could have an impact on someone's life in your community. Is there any way you'd reconsider, Mrs. Rutledge?"

Rutledge, a retired bookkeeper, says she gave in to the pressure from the solicitor and finally agreed to do it. She handed envelopes to her neighbors. In 2011, Rutledge quit her job on the advice of her physician, as cancer had spread through her body.

She becomes silent upon being informed that 70 percent of the money the institute raised in the 2009 campaign for which she and 500,000 other Americans volunteered went to a telemarketing company.

"That's very disturbing," she says. "I'm very disappointed. I'm feeling sick right now. I'm just totally not expecting this."

It helps flesh out just how many of the big health issue charities aren't what they claim to be.

The tactics described in this article seem consistent with what appears to be the real unspoken mission of these charities - to divert funding, energy, and focus from the very real and very effective therapies available in alternative medicine. In other words, it's a way of keeping people locked into big pharma and big health-care "solutions" which are so profitable to the psychopaths in charge, yet so detrimental to the public health.