Despite a moratorium on nuclear testing, the nuclear arms race continues unabated at very high costs. In addition to the startling cases of LLNL's mismanagement of dangerous materials and 'accidental' releases, the facilities are still testing every radioactive component of a nuclear bomb in open air, according to sources.

Malignant melanoma (skin cancer) rates are six times higher among children born in Livermore; melanoma has been linked to radiation exposure. And the amount of radiation which has been expelled from the lab since its inception is equivalent to that released from the bombing of Hiroshima. Most disturbingly, the Livermore community is largely unaware of what the lab is actually doing and what its potential impacts are on its health and the environment.

Abby Martin: "The United States has the biggest weapons arsenal in the world and is the only country who has ever used nuclear bombs during war. All of the nuclear weapons stockpile management and nuclear weapon technology come from two locations in the United States: Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, which is surrounded by a giant plot of desert, and Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, a square-mile facility located right next to a city of 90,000 people. If a large-scale disaster or nuclear accident happened here, it would affect the entire Bay Area - comprised of San Francisco/Oakland - with seven million people living in it. This blue well behind me is used to measure radioactive runoff from the Lawrence Livermore Lab."

Abby Martin Narration (c. 0:36): "The United States used to blow up full-scale nuclear weapons in open air until the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which permitted the continuation of nuclear testing underground. In 1992, Congress passed the Nuclear Testing Moratorium Act, which banned all nuclear testing. However, the treaty is not yet ratified. And the U.S. still has over 5,000 nuclear weapons, 2,000 of which are on readiness alert at all times. To compensate for the loss of full-scale underground nuclear testing, the Department of Energy created the Stockpile Stewardship Program, which built new facilities that test different components of a nuclear weapons explosion, using super computers to put them all together.

"Most of the PR surrounding the Lawrence Livermore Lab gives the impression that it's a technology innovator, working to harvest the energy of the sun to create clean energy for the world. As it turns out, out of the Lawrence Livermore Lab's $1.5 billion dollar annual budget, less than 1% is alternative energy; the rest is defence and nuclear weapons development.

"Another, more elusive, site buried in the hills behind the Lawrence Livermore Lab is called Site 300, a live-fire explosives test range where they blow up highly radioactive compounds used to simulate many of the nuclear systems designed at the lab. Site 300 is mountainous with many watersheds and canyons making contamination easy to spread and clean-up extremely difficult. At Site 300, we found that they are testing depleted uranium and tritium, the radioactive hydrogen in the hydrogen bomb, in open air tests. Site 300 happens to be located in a very high-velocity wind area.

"We took a closer look at Lawrence Livermore Lab and Site 300 and found out if the Livermore community is aware of its impact on their health and the environment and the potential danger it poses to the entire San Francisco Bay Area."

Abby Martin (c. 2:25): "Do you know about the Lawrence Livermore Lab?"

Livermore Man: "Yes."

Livermore Woman: "I mean it's common knowledge to grow up in Livermore - "

Livermore Man B: "Oh, here we go."

Abby Martin: "What?"

Livermore Woman B: "I'm aware of it, yeah."

Abby Martin: "What is it that you think they do there?"

Livermore Woman C: "At the Lab? Oh, it's a government [Shrugs], testing on all kinds of different things?"

Livermore Man B: "I'm not really educated to what exactly, what they do. You gonna tell me?"

Livermore Woman C: "I know they do a lot of research and they have, like, the top scientists from all over the world that work there."

Livermore Woman B: "They used to do, like, nuclear devices. But to my knowledge they don't really do that anymore."

Livermore Man C: "Well, what I think they do there is research and development."

Abby Martin: "What do you think it is they do there?"

Livermore Man: "I worked there for nearly 30 years."

Abby Martin: "So, what did you do there?

Livermore Woman B: "I don't know. My dad works in a machine shop there. [Laughs] I don't know what he does, though. [Laughs]"

Marylia Kelley (Tri-Valley CAREs): "In many ways, Livermore is a community that's in denial. It is also a community that I would call disempowered because you have a super-secret nuclear weapons laboratory and a community around it that's supposed to not ask questions."

Abby Martin Narration (c. 3:39): "We went to the lab in Site 300 to try to find out more."

Site 300 Armed Military Gatekeeper: "Can you just turn that off please? [Leaving Gate Booth]"

Abby Martin: "Isn't this publicly-funded property? [From Vehicle]"

Site 300 Armed Military Gatekeeper: "The Federal, um, could you turn it off just to make? I gotta make, I gotta call my captain. [Approaching Vehicle]"

Site 300 Armed Military Captain: "Um, could you go ahead and turn the camera off?" [Approaching Vehicle; Camera Cuts Out]"

Abby Martin: "I don't know; I've read somewhere that they were testing depleted uranium. I was, like, that can't be true. [Inside a Reception Area]"

Receptionist Woman: "No, nothing nuclear."

Scott Yundt (Tri-Valley CAREs): "What we've been able to place together from FOIA requests and from public documents is that they've released over a million curies of radiation from the lab since 1953 when they opened. That's about the same amount of radiation that was released in the bombing of Hiroshima."

Marylia Kelley (Tri-Valley CAREs): "The state health department did a study of childhood cancers and this was a record study covering 30 years. And they found that children born in Livermore have six times the expected rate of malignant melanoma.

"The study also found that, for one decade, there was a threefold increase in brain cancer in Livermore children."

Abby Martin (c. 4:47): "Do you think that there's any sort of impacts on the environment or to the health of the community with the testing that they're doing there? [Outside in Downtown Livermore]"

Livermore Man: "Probably very little over what most all of us do everyday. [Shrugs]"

Livermore Woman B: "None that haven't been around since I was a kid. [Shrugs] So, I don't know. [Laughs] I mean I survived. [Young Woman Laughs and Shrugs]"

Livermore Woman C: "Yeah, 'cos they've had some problems with the, you know, ground w-, releases of some of the poisons and - "

Livermore Man D: "I know that there was plutonium in a park near my house when I was growing up."

Abby Martin Narration (c. 5:16): "During the '70s and '80s, the Lawrence Livermore Lab was flushing radioactive materials, including plutonium down the drain. And it was recycled by the City of Livermore's sanitation department as compost. The City then gave away the toxic compost as landscaping.

"Local residents around the lab have even coined a neighbourhood park, plutonium park, which is located adjacent to a school.

Marylia Kelley (Tri-Valley CAREs): "They kept a log book, you know, a guest register. So, people signed it, but one day the lab showed up and took it with them. And it's never been seen again. So, there's no way to track who has this plutonium-contaminated sludge or if the particular bit of sludge they took home has plutonium contamination in it or not.

"And, in the midst of all this, Livermore Lab went and got some of this sludge because they were interested in looking at the uptake of plants after a nuclear war."

Livermore Man D: "Obviously, most cities don't dump plutonium into their sewage treatment plants. So, that's a unique experience to our area."

Abby Martin Narration (c. 6:26): "One of the most impressive PR campaigns coming from the lab is the National Ignition Facility (or the NIF)."

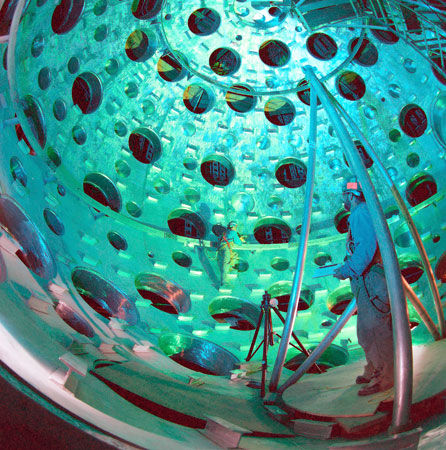

Scott Yundt (Tri-Valley CAREs): "It's a mega-laser that they love to talk about how it's gonna save the world through creating nuclear fusion energy. Most of what the National Ignition Facility is for is 'stockpile management.' And it's really a way for them to test nuclear weapon components because it creates an environment - in that chamber - that is similar to the environment created by a nuclear weapons explosion."

Abby Martin Narration (c. 7:01): "Just like many war technologies that the U.S. government rebrands as peace through force, the 'Stockpile Stewardship' program is nothing more than a cloak on the continued and unabated nuclear arms race."

Scott Yundt (Tri-Valley CAREs): "We have a nuclear-weapons-complex that is still stuck in the Cold War era."

Marylia Kelley (Tri-Valley CAREs): "80% of the American population tell pollsters that they would feel safer if no county, including the United States, had nuclear weapons."

Abby Martin Narration: "Despite the moratorium, we continue to find a way to test nuclear weapons. But by testing each component of a nuclear bomb separately with Site 300, the NIF, and super computers, they're able to pacify the public. However, in the back of our minds, we all know that at any moment - by mistake, by miscalculation, or by madness - life, as we know it, could end on this planet.

"How is the looming threat of nuclear annihalation affecting our daily lives?"

Transcript by Felipe Messina for Media Roots

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter