The remains, found in the valley of the River Tjonger, Netherlands, provide direct evidence for a prehistoric hunting, butchering, cooking and feasting event. The meal occurred more than 1,000 years before the first farmers with domestic cattle arrived in the region.

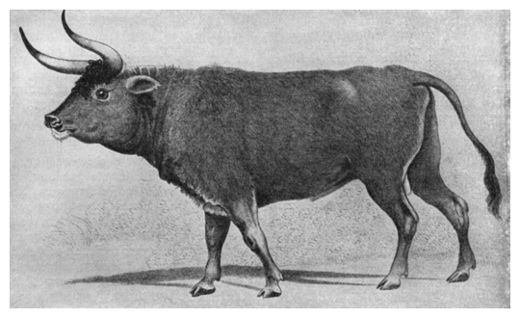

Although basic BBQ technology hasn't changed much over the millennia, this prehistoric meal centered around the flesh of an aurochs, a wild Eurasian ox that was larger than today's cows. It sported distinctive curved horns.

Another big difference is how meat was obtained then.

Prummel and colleague Marcel Niekus pieced together what happened by studying an unearthed flint blade found near aurochs bones. These show that after the female aurochs was killed, hunters cut its legs off and sucked out the marrow.

According to the study, the individuals skinned the animal and butchered it, reserving the skin and large hunks of meat for carrying back to a nearby settlement. Chop marks left behind by the flint blade show how the meat was meticulously separated from the bones and removed.

Burn marks reveal that the hunters cooked the meaty ribs, and probably other smaller parts, over an open fire. They ate them right at the site, "their reward for the successful kill," Prummel said.

The blade, perhaps worn down from so much cutting, was left behind and wound up slightly scorched in the cooking fire.

Niekus told Discovery News, "The people who killed the animal lived during the Late Mesolithic (the latter part of the middle Stone Age). They were hunter-gatherers and hunting game was an important part of their subsistence activities."

The researchers suspect these people lived in large settlements and frequented the Tjonger location for aurochs hunting. After the Iron Age, the area was only sparsely inhabited -- probably due to the region becoming temporarily waterlogged -- until the Late Medieval period.

Aurochs must have been good eats for Stone Age human meat lovers, since other prehistoric evidence also points to hunting, butchering and feasting on these animals. A few German sites have yielded aurochs bones next to flint tool artifacts.

Aurochs bones have also been excavated at early dwellings throughout Europe. Bones for red deer, roe deer, wild boar and elk were even more common, perhaps because the aurochs was such a large, imposing animal and the hunters weren't always successful at killing it.

At a Mesolithic site in Onnarp, Sweden, for example, scientists found the remains of aurochs that had been shot with arrows. The wounded animals escaped their pursuers before later dying in a swamp.

The aurochs couldn't escape extinction, though.

"It became extinct due to the destruction of the habitat of the aurochs since the arrival of the first farmers in Europe about 7500 years ago," Prummel said. "These farmers used the area inhabited by aurochs for their dwellings, arable fields and meadows. The aurochs gradually lost suitable habitat."

The last aurochs died in 1627 at a zoo in Poland.

Reader Comments