© Frank LukasseckStonehenge, end of the Great Stones Way.

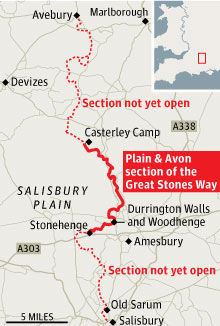

The Great Stones Way is one of those ideas so obvious it seems amazing that no one has thought of it before: a 38-mile walking trail to link England's two greatest prehistoric sites, Avebury and Stonehenge, crossing a landscape covered with Neolithic monuments.

But like any project involving the English countryside, it's not as straightforward as it might seem. The steering group has had to secure permission from landowners and the MoD, who use much of Salisbury Plain for training. They hope to have the whole trail open within a year, but for now are trialling a 14-mile southern stretch, having secured agreement from the MoD and parish councils. The "Plain & Avon" section leads from the iron age hill fort of Casterley Camp on Salisbury Plain down the Avon valley to Stonehenge. Walkers are being encouraged to test the route, and detailed directions can be found on the Friends of the Ridgeway

website.

It's an area all but the boldest have avoided: negotiating the MoD areas needed careful planning. Few walkers come here and not a single garage or shop along the Avon valley sells local maps. The Great Stones Way should change that.

What makes the prospect of the Great Stones Way so exciting is the sense that for more than a millennium, between around 3000 and 2000BC, the area it crosses was the scene of frenzied Neolithic building activity, with henges, burial barrows and processional avenues criss-crossing the route.

© n/aGreat Stones Way map

At Casterley Camp, high on Salisbury Plain, it takes me a while to realise what is strange about the landscape, as wild and empty as anywhere in southern England, and with a large burial mound directly ahead. Then it hits me: this is perfect high grazing country, but there's not a single sheep. Maybe they have read the MoD notice which points out that "'projectile' means any shot or shell or other missile or any portion thereof", and that over much of what you can see you're liable to be hit by one. You can also be arrested without a warrant. But the trail cleverly and legally threads its way past the firing ranges towards a delightful and ancient droving road that plunges down between cow parsley to an old farm.

Five minutes in we are passed by a lone woman wearing Dolce & Gabbana sunglasses and heading determinedly towards the shooting area, where the red flags are up to signify that it's a "live" day. In a Kensington and Chelsea accent, she tells us that she regularly drives down from London as it's one of the few places "where you don't run the risk of meeting anybody else". I murmur that this might be because they know they'll get shot at. "Oh, I love all that. It gets my endorphins going. I got back to the car once and found it ringed by military police. When I told them that I just enjoyed the walking, they didn't believe me. They said, 'How can you claim to enjoy walking when you don't have a dog?'"

One animal practising its duck-and-cover technique here is the remarkable great bustard, recently reintroduced to the UK after its local extinction two centuries ago. At 40lbs, the male bird is one of the largest flying animals in the world, so it's unmistakable even for the most hesitant birdwatcher. As we reach an isolated farm building, we pass a Land Rover full of enthusiasts heading off to track some down.

The trail curves below to cross and then follow the Avon, a river that loomed large in the affairs of Neolithic man. It was along the Avon that the bluestones of the Preseli hills in Wales are thought to have been transported by boat to Stonehenge, after being moved an almost unimaginable distance around both the Pembrokeshire and Cornish peninsulas to the river mouth at Christchurch.

There are some pretty villages along the upper Avon: Enfold, with its flint and stone church, and old funeral wagon in the nave; Longstreet, with the Swan pub appearing at the right moment for a lunchtime reappraisal of the route; Coombe and Fittleton, with their judas trees, mill ponds and dovecotes. At Figheldean (pronounced "file-dean"), an allotment holder tells me he doesn't grow courgettes "because they're foreign food".

© AlamyWoodhenge, Wiltshire Woodhenge, Wiltshire.

It's a peaceful valley to stroll along, with some beautiful stretches under beech trees and past bluebell woods. Which is why it comes as a shock to have to stop for a couple of tanks to trundle past at Brigmerston ford. The route follows the tank tracks back across the river and out onto the plain, so the last stretch again has wide-open vistas of the prehistoric landscape. At Durrington Walls, the trail cuts through a huge enclosed area where the builders of Stonehenge may have lived - the site is aligned to face sunset on the summer solstice - and on past Woodhenge, with its concentric circles of wooden posts (marked now by concrete posts).

As the walk gets into its finishing stride, you pass the King Barrows still sleeping along their ridge, some of the few sites that remain unexcavated (the local farmer didn't want the trees cut down), and the mysterious Cursus group of Bronze Age barrows, so named because 18th-century antiquarian William Stukeley thought it must have been built by the Romans for chariot races. Across a meadow land of dandelions and buttercups, the familiar silhouette of the stone and lintel circle finally appears, at the end of the processional avenue that once led there from the river. In the distance, the stones themselves are a flat grey. What gleams all around them, like fish circling, is the traffic on the A303.

I can't help thinking how much better it is to arrive at Stonehenge on foot. The comparison that comes to mind, and which I know well, is the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu. The experience of trekking to both sites is immeasurably richer, not just because you've "earned it", but because both sets of ruins are only properly understood in the context of the sacred landscape that surrounds them.

For details of this 14-mile section of the walk, and accommodation and transport, see the Friends of the Ridgeway website

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter