© John SmithFire at Bonaire oil storage terminal

A still-smoldering fire that raged out of control for two days at an oil storage facility on the Caribbean island of Bonaire has left residents shaken and wondering how island wildlife, which drives tourism, will fare in the aftermath. And with echos of the BP

Deepwater Horizon, they wonder how such a disaster, consuming 20,000 barrels of oil products at a Venezuelan-owned terminal called BOPEC, could continue unabated for so long.

Island broadcaster and environmentalist Sean Paton suggested that the facility's safety plan was lacking. "One might ask," added Paton, "'What safety plan?'"

A lightning strike reportedly started the fire on Wednesday, sending black clouds billowing 10,000 feet over this small Dutch-ruled island, which is one of the hemisphere's most popular dive locations and home to several rare species of plants and animals.

"The island is a paradise of biodiversity," said ornithologist Carlos Botero in a phone interview Friday. "It contains some of the most amazing species you'll find anywhere." Botero did field work on Bonaire in 2002 and 2003.

The director of a non-profit organization that manages Bonaire's two national parks wrote in an e-mail on Friday that while the smoke "hangs like a mushroom over BOPEC," a full damage assessment will take some time. "No animal has died, no plant has lost a leaf," STINAPA's Elsmarie Beukenboom wrote.

But Paton calls early indications "grim." In a

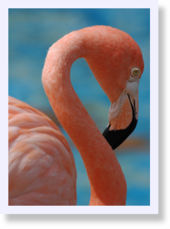

video, he shows evidence of pollution on beaches and water where oily rain fell. A salt water lagoon just yards from the oil facility appears to have been the hardest hit by the contaminated rain. Oil in Goto Meer has raised concerns for the island's best known inhabitant: the pink American Flamingo (

Phoenicopterus ruber).

© Elsmarie BeukenboomFlamingo, Bonaire

Large flocks of the birds feast on brine shrimp in Goto Meer, and also favor the island as one of the prime breeding sites in the Caribbean. An estimated 5,000 flamingos live on the island. Over two hundred species of birds have been sighted at Goto Meer, which is listed as an internationally important wetland under the Ramsar Convention.

Ornithologists are also concerned about possible effects of the oil fire on the small and threatened community of brightly-colored parrots called Loras (

Amazona barbadenis). The subspecies found on Bonaire has dwindling populations on a few other islands (they're already extinct in Aruba) and Bonaire has been called "the species' best chance" for survival. The same is likely true for many other plants and animals found on this small, jewel-like island.

By Saturday afternoon, park rangers were beginning to find the first victims of the oil disaster: several water birds and fish discovered dead in Goto Meer. A team of researchers from the Netherlands is being organized to help access the full damage caused by the BOPEC fire.

Bert Poyck speaks for many Bonaire residents when he talks about the shock he felt when he first saw flames and smoke pouring from the storage tanks he had passed countless times traveling around the island while photographing wildlife.

"You think everything is safe," says the man who retired here from the Netherlands a decade ago, drawn by the "stillness, peace and serenity" of the island. "You think these [oil tanks] must have lightening [rods]... So we wonder how it all could happen?"

It's a question, of course, that has been repeated recently throughout Gulf Coast communities in the United States; in Michigan in July when a burst pipeline dumped 800,000 gallons of oil into the Kalamazoo River; and in scores of other places around the world where petroleum regularly leaks, gushes, explodes or burns -- without attracting all the media attention devoted to the BP disaster in our backyard.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter