© Unknown

If modern civilization collapsed, could the survivors hope to rebuild using our massive stores of data? Unless we can come up with something way more permanent to put them on in the near future, we probably shouldn't bank on it.

A recent article by Tom Simonite and Michael Le Page in

New Scientist tackles this question by positing a minor cataclysm: something bad enough to tear apart civilization as we know it, but not quite enough to kill off humans entirely. Candidates include a pandemic, a financial collapse that would make 2008's pale in comparison, a severe natural disaster, or just the slow accumulation of decay in society's foundations.

The question, then, is in the absence of most of the raw materials that powered the construction of our current industrial civilization - there wouldn't be nearly enough fossil fuels to rebuild from scratch, for instance - whether the survivors of this collapse could make use of the one great resource we would leave behind in huge quantities: information. If we could leave behind the equivalent of a cheat sheet for these post-apocalyptic survivors, could they perhaps bypass the trial and error of rebuilding science and jump straight to the achievements of the 21st century?

The problem with that is how we could possibly hope to preserve all that data. The world's estimated stored data runs well into the petabytes (that's millions of gigabytes), and in order to contain so much data information technology has taken a turn for the short-lived and unstable. We still have readable clay tablets from millennia ago and legible paper from centuries in the past, but their modern equivalents could not reasonably hope to survive that long.

Hard drives were never meant for long-term data storage, and so relatively little effort has been putting into determining their maximum possible lifespan. Other common formats, like CDs and magnetic tape, are generally estimated to only last between five and ten years, particularly if poorly preserved, which is a reasonable assumption in most post-apocalyptic scenarios. Flash drives, as well, probably can only be counted on for about a decade.

Very few of the world's data centers - where the internet's workhorse servers are housed - are built to withstand natural disasters, and even fewer are built to be self-sustaining in the event that humans get distracted by the end of the world. Under those conditions, data would likely degrade quickly.

Even the success stories in data retrieval come with a whole lot of qualifications. For instance, a trustee at Great Britain's computing museum was recently able to retrieve all the data from a hard drive that had been switched off since the early 80s. However, that drive was only 456 megabytes, and it's hard to say whether researchers in the late 2030s would have similar success retrieving data from the new terabyte hard drives that are hitting the market.

This is because the storage density on modern hard drives is many, many times that of their 80s predecessors, which makes them more fragile and vulnerable to degradation. The relatively big bits of data on the 456 megabyte drive could weather minor damage that would wipe out the much smaller bits in modern hard drive, so the resilience of the older hard drive isn't necessarily a great indicator of the toughness of its modern counterpart.

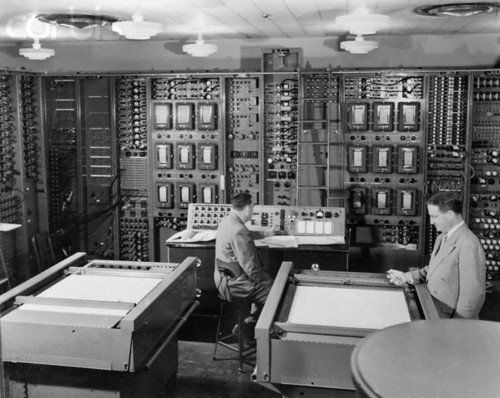

Then there's the recent case of Dennis Wingo and Keith Cowing, who have been working at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California to recover data from old magnetic tapes. Although the tapes were themselves perfectly stored, it took months of painstaking work to recover the original high-resolution images. To accomplish even this relatively simple task (imagine trying to do the same with a terabyte hard drive), they needed a ton of funding and had to basically reinvent abandoned retrieval technology. That probably would have been impossible if they had not been able to rely on the assistance of a retired NASA engineer who had worked on the original project in the sixties. Those are a whole lot of resources the survivors of a mild civilization collapse wouldn't have access to. (Then again, you never know.)

There are some options for the long-term preservation of data in ways that would be relatively easily retrievable in the event of catastrophe, but most enterprises in this area have sputtered because of a lack of commercial interest. One promising possibility is the Rosetta disk, which can hold a whopping 13,500 pages on a disk the size of a nickel and would only require future humans to have access to a decently high-powered microscope. Compared to needing a working laptop and charger to plug in a USB hard drive, that really isn't all that much.

Do as our ancestors, put the data in a permanent medium. Do they think an optical medium is going to stand the test of time? I have had several music CDs begin to break down just after a few years of sitting on a shelf. I suppose this is why the ancient civilizations carved stone tablets.