It's a wonder the Greeks accomplished as much as they did, as many of their homes seem to have doubled as pubs and brothels. This finding, from new analyses of archaeological remains, could explain why previous hunts for evidence of ancient Greek taverns have been fruitless.

Plays from classical Greece describe lively taverns, but no one has ever unearthed their real-life versions. Clare Kelly Blazeby at the University of Leeds, UK, suspected that archaeologists were missing something, so she took a new look at artefacts from several houses dotted around ancient Greece, dating from 475 to 323 BC.

These had all yielded the remains of numerous drinking cups, and so had been assumed to be wealthy residences. Kelly Blazeby now believes a more likely explanation is that the residents regularly sold wine. Her analysis suggests that many of the houses had hundreds of cups - far too many for a building used only as a residence, she says. Other archaeological artefacts suggest the houses were used for other functions too.

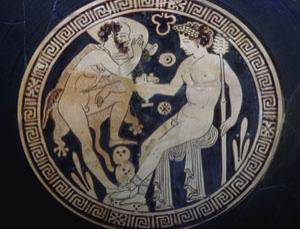

"This blows apart everything that people think about drinking in classical Greece," says Kelly Blazeby, who is presenting her findings on 10 January at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She is not alone. Allison Glazebrook of Brock University in St Catharines, Ontario, Canada, will tell the same conference that some of the houses doubled as brothels. Telltale signs that Glazebrook found include erotic graffiti and objects, and clusters of clay drinking cups.

"This has a real impact on how we view the economy in classical Greece," says Kelly Blazeby. "A lot of trade and industry was based within the home."

Lin Foxhall at the University of Leicester, UK, a specialist on life in ancient Greece, agrees. She says Kelly Blazeby's analysis highlights "the diversity of activities and types of residents that might have inhabited the buildings we call 'houses' in the highly urbanised cities of classical Greece".

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter