|

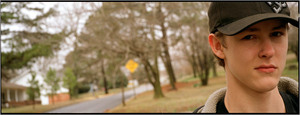

| ©Angel Franco/The New York Times |

| Billy Wolfe, a target of bullies for years, at the school bus stop near his home in Fayetteville, Ark. |

All lank and bone, the boy stands at the corner with his younger sister, waiting for the yellow bus that takes them to their respective schools. He is Billy Wolfe, high school sophomore, struggling.

Moments earlier he left the sanctuary that is his home, passing those framed photographs of himself as a carefree child, back when he was 5. And now he is at the bus stop, wearing a baseball cap, vulnerable at 15.

A car the color of a school bus pulls up with a boy who tells his brother beside him that he's going to beat up Billy Wolfe. While one records the assault with a cellphone camera, the other walks up to the oblivious Billy and punches him hard enough to leave a fist-size welt on his forehead.

The video shows Billy staggering, then dropping his book bag to fight back, lanky arms flailing. But the screams of his sister stop things cold.

The aggressor heads to school, to show friends the video of his Billy moment, while Billy heads home, again. It's not yet 8 in the morning.

Bullying is everywhere, including here in Fayetteville, a city of 60,000 with one of the country's better school systems. A decade ago a Fayetteville student was mercilessly harassed and beaten for being gay. After a complaint was filed with the Office of Civil Rights, the district adopted procedures to promote tolerance and respect - none of which seems to have been of much comfort to Billy Wolfe.

It remains unclear why Billy became a target at age 12; schoolyard anthropology can be so nuanced. Maybe because he was so tall, or wore glasses then, or has a learning disability that affects his reading comprehension. Or maybe some kids were just bored. Or angry.

Whatever the reason, addressing the bullying of Billy has become a second job for his parents: Curt, a senior data analyst, and Penney, the owner of an office-supply company. They have binders of school records and police reports, along with photos documenting the bruises and black eyes. They are well known to school officials, perhaps even too well known, but they make no apologies for being vigilant. They also reject any suggestion that they should move out of the district because of this.

The many incidents seem to blur together into one protracted assault. When Billy attaches a bully's name to one beating, his mother corrects him. "That was Benny, sweetie," she says. "That was in the eighth grade."

It began years ago when a boy called the house and asked Billy if he wanted to buy a certain sex toy, heh-heh. Billy told his mother, who informed the boy's mother. The next day the boy showed Billy a list with the names of 20 boys who wanted to beat Billy up.

Ms. Wolfe says she and her husband knew it was coming. She says they tried to warn school officials - and then bam: the prank caller beat up Billy in the bathroom of McNair Middle School.

Not long after, a boy on the school bus pummeled Billy, but somehow Billy was the one suspended, despite his pleas that the bus's security camera would prove his innocence. Days later, Ms. Wolfe recalls, the principal summoned her, presented a box of tissues, and played the bus video that clearly showed Billy was telling the truth.

Things got worse. At Woodland Junior High School, some boys in a wood shop class goaded a bigger boy into believing that Billy had been talking trash about his mother. Billy, busy building a miniature house, didn't see it coming: the boy hit him so hard in the left cheek that he briefly lost consciousness.

Ms. Wolfe remembers the family dentist sewing up the inside of Billy's cheek, and a school official refusing to call the police, saying it looked like Billy got what he deserved. Most of all, she remembers the sight of her son.

"He kept spitting blood out," she says, the memory strong enough still to break her voice.

By now Billy feared school. Sometimes he was doubled over with stress, asking his parents why. But it kept on coming.

In ninth grade, a couple of the same boys started a Facebook page called "Every One That Hates Billy Wolfe." It featured a photograph of Billy's face superimposed over a likeness of Peter Pan, and provided this description of its purpose: "There is no reason anyone should like billy he's a little bitch. And a homosexual that NO ONE LIKES."

Heh-heh.

According to Alan Wilbourn, a spokesman for the school district, the principal notified the parents of the students involved after Ms. Wolfe complained, and the parents - whom he described as "horrified" - took steps to have the page taken down.

Not long afterward, a student in Spanish class punched Billy so hard that when he came to, his braces were caught on the inside of his cheek.

So who is Billy Wolfe? Now 16, he likes the outdoors, racquetball and girls. For whatever reason - bullying, learning disabilities or lack of interest - his grades are poor. Some teachers think he's a sweet kid; others think he is easily distracted, occasionally disruptive, even disrespectful. He has received a few suspensions for misbehavior, though none for bullying.

Judging by school records, at least one official seems to think Billy contributes to the trouble that swirls around him. For example, Billy and the boy who punched him at the bus stop had exchanged words and shoves a few days earlier.

But Ms. Wolfe scoffs at the notion that her son causes or deserves the beatings he receives. She wonders why Billy is the only one getting beaten up, and why school officials are so reluctant to punish bullies and report assaults to the police.

Mr. Wilbourn said federal law protected the privacy of students, so parents of a bullied child should not assume that disciplinary action had not been taken. He also said it was left to the discretion of staff members to determine if an incident required police notification.

The Wolfes are not satisfied. This month they sued one of the bullies "and other John Does," and are considering another lawsuit against the Fayetteville School District. Their lawyer, D. Westbrook Doss Jr., said there was neither glee nor much monetary reward in suing teenagers, but a point had to be made: schoolchildren deserve to feel safe.

Billy Wolfe, for example, deserves to open his American history textbook and not find anti-Billy sentiments scrawled across the pages. But there they were, words so hurtful and foul.

The boy did what he could. "I'd put white-out on them," he says. "And if the page didn't have stuff to learn, I'd rip it out."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter