All is not well in the playgrounds of the world, says an international group of child therapists, including several prominent Canadians.

|

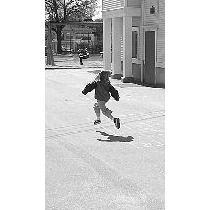

| ©Vancouver Sun

|

| A UNICEF report found that British children are among the most unhappy in the developed world. Outdoor, unstructured and loosely supervised play is missing in children's lives, the report added.

|

In a letter published Sunday in the U.K.'s Daily Telegraph, 270 professionals blame "the marked deterioration in children's mental health" on an overprotective society and too much "sedentary entertainment."

It cites a recent UNICEF report that found British children are among the unhappiest in the developed world.

In particular, outdoor, unstructured, and loosely supervised play is missing in children's lives, resulting in "an explosion in children's clinically diagnosable mental health problems," reads the letter.

Whether it's time spent playing video games and with "over-elaborate commercialized toys" that inhibit rather than stimulate creative play -- or whether it's parents' anxiety about "stranger danger" -- children are getting few opportunities to engage in creative, interactive play, says the letter.

"We have to trust children to play," said Bertrand Dupuis, an educator at the Montreal Children's Hospital who signed the letter.

"You know, very small children are quite happy playing with an empty cardboard box. These days, we seem to isolate our children from each other, and they aren't given the opportunities they need to play together, to grow as people."

The effects can range from a lack of empathy to fear of the outside world, the experts say."One line of reasoning suggests that, unless we engage in symbolic, dramatic play, we don't develop a good sense of empathy with others," said Henderikus Stam, a psychology professor at the University of Calgary, who also signed the letter.

"Play is crucial to understanding what it's like to be some other kind of person."

And when children see so much real and simulated death in violent video games and TV, "it erodes [their] sense of security," Dupuis said.

"I believe we're seeing more children who aren't sleeping well, who are more stressed -- sometimes because their own parents are facing more stress. That's leading to more of them visiting doctors and psychologists -- but also it's because their parents are so insecure about their ability to parent well, they just want a professional to tell them there's nothing wrong with their child."

Saskatoon mother Karen Farmer says she tries hard not to meddle in her six-year-old daughter's play. She said her girl spends a lot of her time playing imaginative games of make-believe with her friends.

"No adult is going to come up with that stuff," said Farmer, adding she understands the impulse of well-meaning parents to be "hyper-vigilant" and to over-program their children's lives.

"But I think a really important part of childhood is autonomy, and negotiating complex challenges and human relations on their own."

"I believe in moderation," said Toronto mother Flavia Ferrero, who has two children, aged nine and 12.

"They play a sport and a musical instrument each, but playtime with friends is completely unstructured. It's up to them what they do."

A similar letter appeared in the Daily Telegraph one year ago, signed by British professionals and academics.

This year's signatories include professionals from Canada, the U.S., Australia, and India.

They say what's needed is a "wide-ranging and informed public dialogue about the intrinsic nature and value of play in children's healthy development, and how we might ensure its place at the heart of twenty-first-century childhood.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter