Pathways of Domestication

Over the years, there have been a number of different thoughts as to how domestication of various animals came about. Some people proposed that early domestication involved a kind of master-subject relationship, where humans guided wild animals to domestication through selective breeding and other techniques. On the opposite end of the spectrum, one theory holds that some domesticates manipulated humans into relationships that benefited the animals, at, possibly, the expense of people.

"Now, we look at it as being much more of a mutualistic relationship between humans and animals," said Fiona Marshall, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. That is, both human and animal reap some kind of benefit through their increasingly co-dependent interactions. But not all relationships begin the same way - there are three different "pathways" to domestication.

Animals such as sheep, goat and cattle became domesticated through the prey pathway. They began as prey for hunters, but when their numbers dwindled, people implemented smarter, more selective hunting practices and likely protected the animals from other predators. Over time, these game management strategies transformed into herding and eventually controlled breeding. By comparison, the directed pathway is seen as a kind of intentional domestication, where people selected animals to domesticate for things such as milk, wool and transportation.

Species most frequently became domesticated through the commensal pathway, Marshall told io9. Here, animals, including dogs, pigs and chicken, came to human settlements to eat refuse or prey on other animals. At some point, the animals developed closer bonds with humans, which eventually grew into a domestic relationship. Researchers have reasoned that Near Eastern Wildcats (Felis silvestris lybica; below) - which are thought to be the ancestors of all domestic cats - became domesticated through a commensal pathway, after they began visiting human settlements to eat rodents. Surprisingly, however, there has been little archaeological evidence to back up this idea.

In the archaeological record, the earliest evidence of a relationship between human and wildcat goes back to 9,500 years ago in Cyprus - at the site of Shillourokambos, archaeologists discovered a wildcat buried with a human. "This suggests that people cared for that cat," Marshall said. "This might have been a really early stage of domestication." The first evidence for actual domestic cats stems from Ancient Egyptian art from 4,000 years ago.

But just what happened during that crucial 5,500-year timespan has been a complete mystery - until now.

Unearthing the Ancient Food Web

Marshall's colleagues in China, led by Yaowu Hu of the Chinese Academy of Science, excavated the Quanhucun archaeological site, located in the village of Quanhucun, Hua County, Shaanxi Province, China. The site, Marshall explained, was an ancient farming village that was part of the ancient Yangshao Culture, which was involved in the early domestication of millet and pigs.

At the site, the scientists found the remains of various animals, including pigs, deer, dogs and rodents. They also found numerous other archaeological features and artifacts, such as houses, storage pits and pottery. Ancient rodent burrows leading to grain-storage pits suggested that the farmers had a major rodent issue - this was also evidenced by the presence of certain crop-storage pots that were designed to protect food stores from rodents.

The team analyzed the carbon and nitrogen isotopes present in the animal and human remains to determine what they ate. The results suggested that the wild herbivores, such as deer and hare, fed on some kind of wild vegetation in the area. The humans, dogs and pigs all had diets rich in millet-based foods; the researchers believe the diets of the dogs and pigs were based on human food remains (from leftovers or garbage) and feces. The rodents also had isotope values indicative of millet products. The cats, on the other hand, appeared to have been preying on animals with a high millet diet, which were most likely those grain-eating rodents.

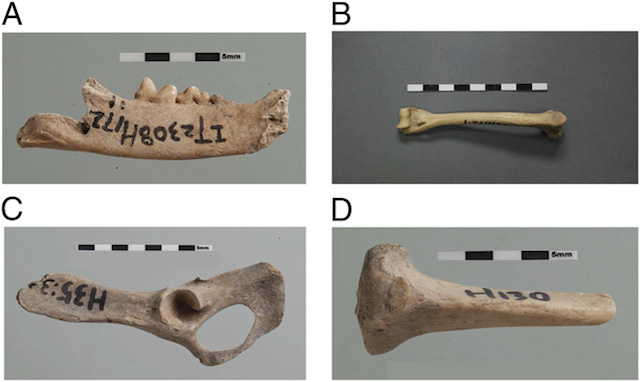

The isotope values of one of cat specimens stood out from the rest. Unlike the other cats, this animal ate far less meat than would be expected if it were actively hunting rodents. The cat may have been unable to hunt for whatever reason and instead lived by scavenging from human food remains, or villagers may have taken care of it. "It certainly wasn't living in a way that a wild cat would normally live," Marshall said. Additionally, another cat specimen had very worn teeth, showing that it survived into old age. "That suggests that cats were doing very well in that environment, whether they were wild or domestic or like feral alley cats today."

The study suggests that the cats were able to carve out a niche in the Chinese farming village. As previous theories had suggested, the cats were drawn to the village because of the abundance of rodents, which were living off of the farmers' food. Here, they had access to year-round food and were possibly cared for by humans after they could no longer hunt - this allowed them to thrive in the new habitat. Humans equally benefited from having a new kind of pest control. Over time, the relationship between cats and humans strengthened, leading to true domestication.

The scientists aren't sure about the cats' lineage. The bones were smaller than European wildcat bones and comparable to those of modern European domestic cats, but there's no DNA evidence yet that the unearthed cats are descendants of the Near Eastern Wildcat, which are not native to the region. It may be the case that these Yangshao cats are semi-domesticated Near Eastern Wildcats that had come from the west along a complex trade network. These animals could also have interbred with Asian wildcats (F. s. ornata and F. s. bieti). Less likely, the cats may have been locally domesticated from the Asian wildcat population, which would mean there's an entirely different domestication history of cats we don't know about. The Chinese researchers are now working with scientists in France to get DNA data and some answers.

Whatever the case, Marshall thinks the work helps us understand what our relationships with cats were initially like. "We now know that humans and cats are historically tied together by food," she said.

Reference: PNAS

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter