Besides, the weather at the time of Saturday's crash was so ideal that even the wind had calmed. After the crash landing, smoke from the ensuing fire lingered over the plane, instead of blowing out across the water.

On top of that, the aircraft model at issue, the Boeing 777, had experienced only two accidents, neither responsible for a death, since it went into service in 1994. And the part that had caused the most recent crash before Sunday's, an engine prone to icing, had been modified. The National Transportation Safety Board noted that the San Francisco plane did not seem to experience a mechanical failure. "The engines indicate that both engines were producing power," Chairman Deborah Hersman said.

So what had gone wrong on this flight, which ended with the deaths of two 16-year-old passengers and the hospitalization of 182 others? Why did the plane, which originated in Shanghai and flew into San Francisco on a routine 10-hour leg from Seoul, Korea, end in a fiery snarl?

With the safety board set to further review the data recorders that detail the final 30 minutes of the flight, Thrush and other New Orleans area pilots, monitoring the news from afar, began to wonder whether the fault might not lie with the pilots.

Too low and too slow

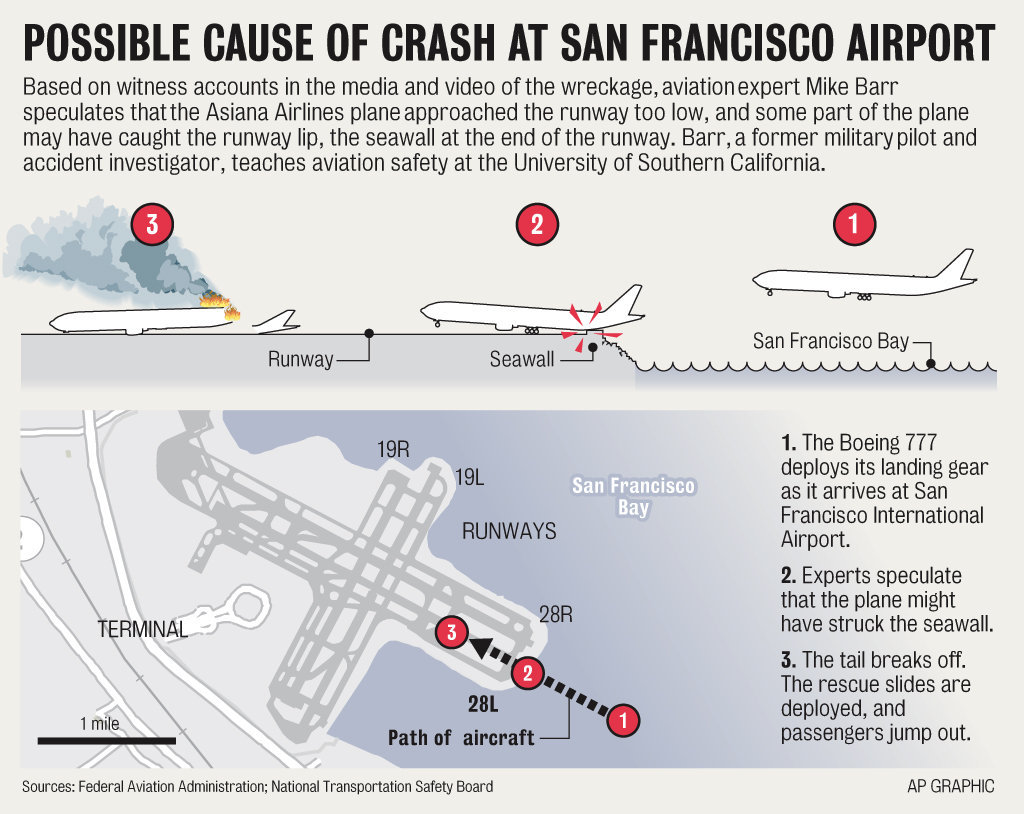

The first thing that struck Thrush was the pattern of the plane's debris. A commercial pilot for 42 years, he noticed that the plane snaked a trail of smoke and fire from the wall that divides San Francisco's Runway 28L from the bay. "Wow," Thrush thought. "They banged the tail on the seawall."

The major lesson that pilots and flight instructors saw in the crash was that the plane was coming in too low and too slowly. That might seem like the perfect combination for a smooth landing, but it's the opposite. Once a pilot realizes that the approach is wrong -- that the plane is aiming short of the runway, as it seems was the case in Flight 214 -- the slowing engines must be revved up to lift the craft to circle around for a second approach. But because the plane is too low, pilots have no time to wait.

Boeing 777s are large, heavy aircrafts, especially designed for long flights such as Asiana 214's crossing of the Pacific Ocean. They do not regularly call on New Orleans, although they will fly into Louis Armstrong International Airport if chartered for a special event such as for the Super Bowl or are diverted for weather or a mechanical error.

Because of the plane's size and weight, if the two engines are at idle, a pull up on the throttle is not felt for seven to 10 seconds. The closer the throttle is to idle, the longer the lag between a pilot's decision and a change in speed. And at landing, every half-second counts.

According to the safety board, Asiana 214 slowed below its target speed of 137 knots 34 seconds before it hit the seawall, and eventually dropped to 103 knots. Seven seconds before impact, there was an attempt to increase the plane's speed.

Three seconds before impact, the plane's automatic alert went off, to warn of an approaching stall. In this situation, the pilot's yoke vibrates to urge an increase in speed, a situation called a "stick shaker." After this occurred on Flight 214, a crew member was recorded calling to halt the landing, to go around again. That happened just 1-1/2 seconds before impact.

"They came in too low and too slow," said Ankur Hukmani, a former commercial pilot who owns the Flight Academy of New Orleans. "We teach that all the time. That is just pilot error." He noted that in videos, Flight 214 appeared to have descended comfortably but to have touched ground about 50 feet short of the runway.

Those 50 feet comprise a major error. Pilots flying 777s are expected to reach the edge of the runway at 50 feet above the ground, the height of a five-story building. To land short of the runway, the pilot of Flight 214 would have been as low as 50 feet when still over the water.

"He should have recognized it and acted accordingly," said Robert Bordes Jr. of Algiers, who has flown corporate jets since 1977. "He should have rejected the landing and gone around."

But it was too low, too late.

"If you're within eight to 10 seconds of hitting the ground, I don't care what you do," said Thrush, who has decades of experience flying into San Francisco on 767s, almost as heavy and slow to respond as the 777. "You're going to hit the ground. It didn't have to happen. It's just too bad that those two young girls had to die."

"I hate to say this, but we always make an example of things like this," said Hukmani. "Too low, and too slow. That means a crash."

"In my opinion it's pilot error, 100%," Thrush said.

An inexperienced pilot?

Flight 214's pilot, Lee Kang-kook, had logged almost 10,000 hours as a commercial pilot, making him among the more experienced in the field. But he had never before flown a 777 into San Francisco and, indeed, had logged only 43 hours on that model.

"Forty three hours? That's nothing," Hukmani said.

Pilots with fewer hours on any one model of plane typically log more hours by flying with more experienced pilots.

After a spate of crashes in the 1990s, Korean airlines such as Asiana worked to undo a pattern that had developed among cockpit personnel because of a cultural belief that employees should respect authority and not correct errors. Though pilots were paired to fly together and correct each other, they were also culturally disposed to respect existent hierarchies.

At 43 hours, Kang-kook was probably "on his way to being let loose," Thrush said.

And perhaps a more experienced pilot who also was in the cockpit did not feel it was polite to step in.

Ideal weather conditions

According to Thrush and other experienced pilots, the landing conditions at the time of Saturday's crash were not unusual.

"The problem with San Francisco the morning they landed the airplane was that it was too beautiful and there were too many things to see," said Andrew Jones, a Denver-based airline pilot who grew up in New Orleans and has often flown 767s into San Francisco during the past 16 years. To reach the runway at San Francisco from the east, Jones noted that pilots enjoy a long, straight approach over the bay. "In my opinion, it's one of the easiest conditions to land in," he said.

Robert Bordes Jr. agreed, assuming the cloud ceiling isn't low and the approach is not over San Francisco's hills. "The mountains tend to reach up and bite you sometimes," he said.

Thrush, who was raised in San Francisco, experienced strong winds on some of the hundreds of occasions when he flew back home. "The wind swoops in through the Golden Gate and turns and comes in through the peninsula."

However, everything was calm Saturday. The smoke lingered over the plane.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter