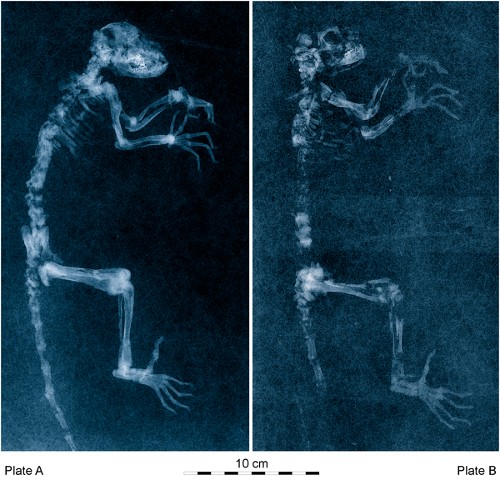

Before I jump into my criticisms of the paper describing Darwinius masillae, Ida's scientific name, I do want to stress how spectacular the fossil really is. The primate fossil record is extremely fragmentary, and if you want to know anything about fossil primates you are going to have to know your teeth. That's usually all that is left of them. Ida, then, is a paleontologist's dream come true. Not only is it a complete specimen but parts of the primate's last meal were preserved inside its stomach and its body outline was marked by bacteria that fed on the decomposing carcass during fossilization. This is the first time a fossil primate has been found exhibiting such extraordinary preservation.

Most of the media reports about Darwinius have only mentioned this point in passing, though. What they are most interested in is its status as a "missing link" between anthropoid primates (monkeys and apes) and their ancient ancestors. As John Wilkins has pointed out the phrase "missing link" is woefully inaccurate, conjuring up images of life ranked in an unbreakable Great Chain of Being put in place by God, but that has not stopped media outlets from running with the idea. Even though the authors of the paper deny making any such statement, the promotional materials they are associated with (most notably the "Revealing The Link" website) play up this angle to a ridiculous degree.

So what is all the hubub about? Why is the History Channel falling all over itself to promote this fossil? It all goes back to a long-standing debate over the origins of anthropoid primates that, until now, has mostly gone on in academic journals and scientific meetings.

Scientists have long debated the question of what earlier primates the earliest anthropoids evolved from. There have been a number of hypotheses proposed, but they have generally centered around three groups: the adapids (an extinct group of lemur-like primates to which Darwinius belongs), the omomyids (an extinct group of tarsier-like primates), and the tarsiers (strange, large-eyed primates with living representatives). Each of these groups has been favored as the progenitors of anthropoids, but which one is the right one?

In order to solve his problem paleo-primatologists have been trying to figure out which of these groups is closest to the anthropoids. It might be impossible to identify a true anthropoid ancestor with certainty, but by figuring out the next closest related group (or sister group) scientists can create and test hypotheses about what an anthropoid ancestor might look like. These determinations are based upon shared derived characters, or particular traits shared by two groups and their common ancestor to the exclusion of other groups.

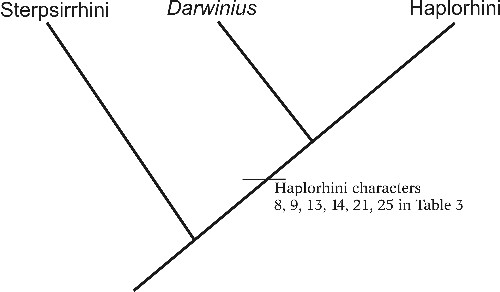

As outlined in the paper "Evolving Perspectives on Anthropoidea" (among others) included in the recent Anthropoid Origins volume, it presently appears that tarsiers and omomyids are the closest groups to anthropoids. This is based upon a combination of fossil, genetic, and morphological evidence. This makes the adapid primates, including Darwinius, a more distant side branch more closely related to living lemurs and lorises.

Not everyone agrees with this, however. Some researchers have long maintained that adapids are better candidates for the ancestors of anthropoids, with Philip Gingerich (one of the authors of the Darwinius paper) being a vocal proponent of this view. It is not terribly surprising, then, that the authors of the Darwinius paper posit that adapids are more closely related to anthropoids than tarsiers and omomyids, and they rely on two tactics to make their case.

The authors of the paper try to frame their hypothesis in a historical manner. They claim that adapids have been barred from a close anthropoid relationship on the basis of soft-tissue characteristics that do not fossilize. This would mean that the association between omomyids, tarsiers, and anthropoids would hang by a nose, but this is not true. As reviewed in popular books like Chris Beard's The Hunt for the Dawn Monkey and technical volumes like Anthropoid Origins, the relationship between omomyids, tarsiers, and anthropoids is based upon a wide array of fossil and neontological data. I can't imagine why the authors of the new paper would suggest otherwise unless they were trying to construct a false historiography in order to show their fossil in a better light.

This shoddy scholarship is matched by a weak attempt to show that Darwinius has more anthropoid-like traits than tarsiers or omomyids do. In order for the authors of the paper to make a convincing case they would have to undertake a careful, systematic analysis of the anatomy of Darwinius in comparison to other primates, yet they did not do this. Instead they combed the literature for 30 traits that might help ascertain the placement of Darwinius in the primate family tree and filled in whether each trait was present or absent in Ida's skeleton.

From what has been presented in the popular press, the authors claim that there are two primary traits that more closely link Darwinius to anthropoids. It appears that Ida did not have a tooth comb (a set of forward-facing incisors) or a grooming claw (a special claw on the foot), two characteristics of living lemurs and lorises (strepsirrhine primates). Since anthropoids lack these traits, too, the authors suggest a close connection, but they have not sufficiently shown that Darwinius is not just showing a case of convergence.

The bottom line is that the hypothesis that Darwinius is closer to anthropoids than tarsiers or omomyids does not have strong support. Even though the authors of the paper constructed a very simple cladogram they did not undertake a full, rigorous cladistic analysis to support their claims. I am baffled as to how they could stress the significance of this fossil without undertaking the requisite research to support their hypothesis.

Is Darwinius important to understanding primate evolution? Of course! It is an exceptionally preserved specimen that could do much to aid our understanding of adapid evolution and paleobiology. The grand claims about it being our ancestor, though, can not be upheld as true. The researchers simply did not do the work to support their case, and even if their language was more reserved in the technical paper they have gone hand-in-hand with the History Channel to create an aura of sensationalism around the fossil. I hardly think this is a responsible way to conduct or communicate science, flooding the media with poorly supported claims, but as reported in the New York Times some of this paper's authors care more about marketing than about good science;

"Any pop band is doing the same thing," said Jorn H. Hurum, a scientist at the University of Oslo who acquired the fossil and assembled the team of scientists that studied it. "Any athlete is doing the same thing. We have to start thinking the same way in science."

This is a shame. I would have hoped that this fossil would receive the care and attention it deserves, but for now it looks like a cash cow for the History Channel. Indeed, this association may not have only presented overblown claims to the public, but hindered good science, as well. As Karen James has suggested, the overall poor quality of the paper and the disproportionate hyping of the find make me wonder if this research was rushed into publication so that the media splash would occur on time. The paper tried to cover so much, so quickly, and contained so many shortfalls that I honestly have to wonder why it was allowed to be published in such a state. Perhaps we will never know, but I am sickened by the way in which a cable network has bastardized a legitimately fascinating scientific discovery, with the scientists themselves going along with it every step of the way. I can only hope that Darwinius will eventually receive the careful analysis it deserves:

Franzen, J., Gingerich, P., Habersetzer, J., Hurum, J., von Koenigswald, W., & Smith, B. (2009). Complete Primate Skeleton from the Middle Eocene of Messel in Germany: Morphology and Paleobiology PLoS ONE, 4 (5) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005723

Laelaps is the science blog of Brian Switek, a science writer based in New Jersey. This blog frequently features his musings on paleontology, evolution, and the history of science. Switek also blogs for Smithsonian magazine's Dinosaur Tracking.

Comment: An interesting comment on the media splash given to this archeological find, especially in view of this article:

Science in Turmoil - Are we Funding Fraud?