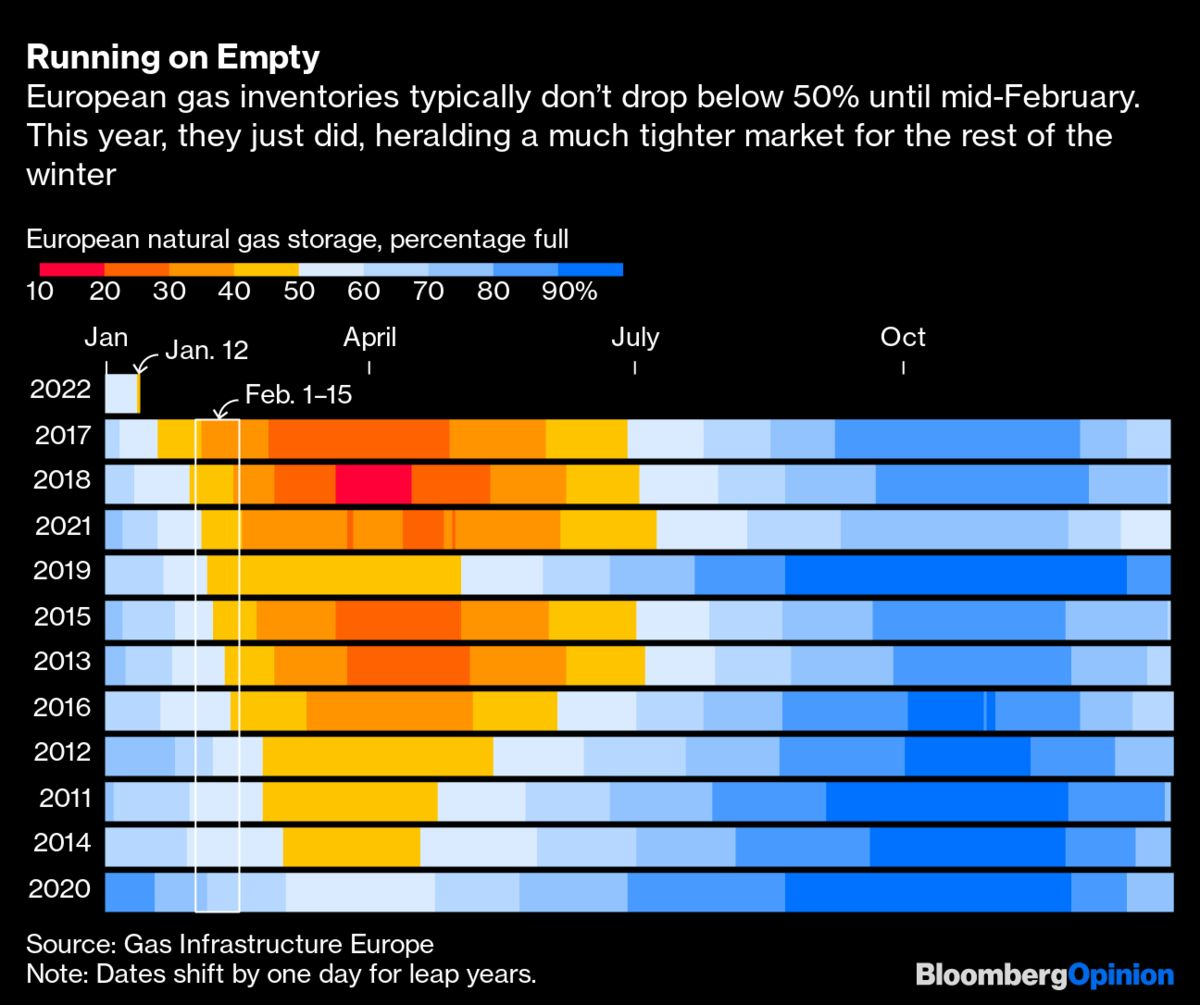

Gazprom is right. On Thursday, Gas Infrastructure Europe, an industry association, announced that European gas inventories had dropped below the key 50% mark of total capacity, down to 49.33% as of Jan. 12. It's the earliest the half-empty mark has ever been reached, beating the previous record by seven days. Typically, Europe's gas inventories don't fall to half until about early-to-mid February. During some mild winters, the inventories don't sink below midpoint until early March.

The biggest ally of Europe in the gas crisis has so far been the weather. Only a month ago, many feared the 50% level would be breached on New Year's day. Unseasonal temperatures cut consumption and helped to avoid that scenario. The arrival of liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargos also alleviated the crunch. Some big energy consumers — like fertilizer companies, glass manufacturers and aluminum and zinc smelters — also shut down production.

Comment: One wonders just how low reserves would be if industry hadn't been shut down, and what the knock on effects of shutting them down will have on critical industries, trade and agriculture? It's not as though Europe has the luxury of losing that production and revenue.

With nearly half of January gone, there are few meteorological signs of the feared cold snap. Indeed, if the current forecasts hold, temperatures may rise above seasonal levels during the second half of the month.

It could still get colder, but typically Jan. 28 marks an inflection point in European winter, when the season starts to gently warm, according to 30-year average trends.

Comment: Except recent years have shown that our planet has entered a period where these trends are no longer applicable. Meanwhile, elsewhere on the planet, including Eastern Europe and Russia, record cold temperatures and snowfall has been documented.

Each day without a cold snap after that date is a day closer to spring — and relief for the gas market. Still, prices for European gas — and electricity — remain elevated, with benchmark gas trading around 75 to 80 euros ($86 to $91.74) per megawatt hour, about 300% above the 2010-2019 average but well below a peak of nearly 188 euros per MWh set in December.

Gazprom is the main reason why - and not because of its tweets. Russia has kept the pressure on the European gas market by turning down supplies.

Comment: Russia offered long term gas contracts, and countries like Serbia and Hungary took advantage of the "incredible" deals, however the belligerent West refused and now its citizens are suffering the consequences of record costs, at a time where inflation and food prices are also soaring, and a great many are reeling from 21+ months of rolling lockdowns.

The Yamal-Europe pipeline, a major conduit of Russian gas into Germany, hasn't shipped a single molecule of gas for 23 consecutive days. Flows via other pipelines remain well below normal levels.

Gazprom says it's meeting all its contractual obligations with customers in Europe. And the customers agree. What the Russian energy behemoth isn't doing, as it does normally in winter, is to offer gas on the spot market above and beyond its long-term contracts.

Why not is a matter of hot debate. Some argue the company doesn't have the gas to sell because domestic demand is running very high and exports to China are rising. Others, however, believe Russia is manufacturing a gas crisis for political leverage over Ukraine.

Comment: Russia might be leveraging its position in the hope that by having long term gas contracts the West might tone down its aggression, and who could blame it?

What's clear is that with half of January gone, and the weather indicating more mild temperatures until February, the biggest risk is no longer a cold winter — but what Russia can do to supplies.

Comment: Europe's puppet politicians might get lucky and this winter may continue to be relatively, unseasonably mild, however recent years have shown that severe frosts are still possible past April, so it's hardly a time to be celebrating. However it seems, whatever happens, it's not a high priority concern for Europe's establishment who are hellbent on attending to another agenda:

- Why Do NATO States Commit Energy Hara Kiri ?

- Pepe Escobar: Exit Nord Stream 2, enter Power of Siberia 2

Also check out SOTT radio's: NewsReal: Kazakhstan on Fire: Why US vs Russia 'Great Game' Could Spark Global Economic Collapse