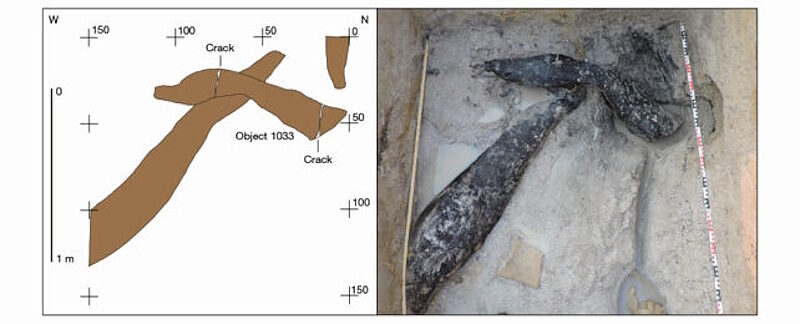

© Dr Kenny BrophyExcavations through the cursus bank at Drumadoon.

A leading team of researchers have discovered what is believed to be a

complete Neolithic cursus set within a rich prehistoric landscape on the Isle of Arran, Scotland.

This monument type is amongst the first that was built by farmers in Neolithic Britain and is huge - measuring 1.1km long and 50 metres wide.

A cursus is a vast Neolithic monument comprised of one or more rectangular enclosures. The cursus on Arran is defined by a large stone, earth and turf bank running around the entire perimeter of the enclosure. Constructing this monument would have involved staggering amounts of labour, transforming the entire local landscape.

This monument type

could date to perhaps as early as 3500 BC, researchers say. It is the most complete example of this site type found in Britain and the opportunity to investigate a cursus bank is very rare and hugely exciting.

Prehistoric field boundaries, clearance cairns and round houses, at least some of which may be contemporary with the monument, have also found in the same landscape, all preserved within peatland, sealing the archaeological layers. Ancient soils representing the original Neolithic land surface, together with cultivated soils from the Bronze Age period, provide an unparalleled opportunity to understand how contemporary farming practice and settlement interacted with the cursus monument and how early farmers transformed this place.

The combination of investigating all these elements together is highly unusual. The inter-disciplinary team from the Universities of Glasgow, Birkbeck, Bournemouth, Reading, Coventry, Birmingham, and Southampton as well as archaeologists from Archaeology Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland, are using archaeological prospection, excavation and geoarchaeology, coupled with cutting-edge environmental scientific techniques, including ancient DNA, to understand how this unique landscape was constructed and used.