Back in the early '60's Jessica Mitford wrote a shocking book — The American Way of Death — that exposed how the funeral industry took advantage of the aggrieved with expensive and unnecessary burial practices. Now we are learning that this $15 billion-a-year business is also unsustainable — and highly destructive to the environment.

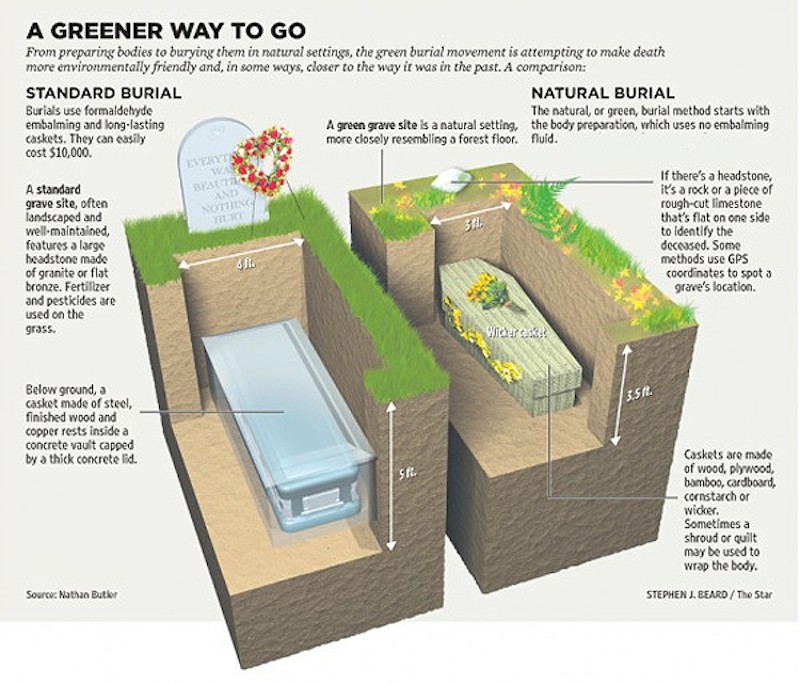

Consider this: the millions of gallons of toxic embalming fluid used to pretty up and "preserve" corpses eventually find their way into the ground, contaminating soil and water resources. And the iron, lead, copper, zinc, and cobalt used in caskets and vaults also contaminate the soil. Even cremation isn't nearly as clean as you might think. Crematories release by-products from embalming fluid, dental fillings, surgical devices, etc.Enter the "Green Burial" movement that advocates burying a body, without embalming, in a biodegradable container that allows direct immersion into the earth — and the body returns to the land and to the cycle of life.

Suzanne Kelly, PhD — author of Greening Death: Reclaiming Burial Practices and Restoring Our Tie to the Earth, (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, September 2015) — has been a chief advocate for this practice. Kelly's work, which she discusses in this podcast with Jeff Schechtman, is beginning to have an impact. She says that today families are starting to push back on non-sustainable practices.

"Death is understood to be a path to environmental protection," says Kelly. "The Green burial offers us the possibility of restoring our lost relationship to the land."

Comment: When ya gotta go...go green! "Dust to dust"...what kind matters!