|

| ©National Geographic/artist's rendering |

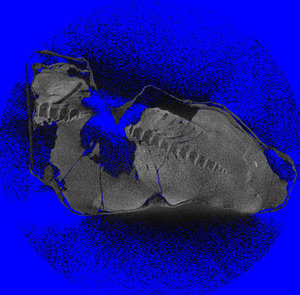

| Dakota, a 67-million-year-old "dino mummy" unveiled today by a British paleontologist, is seen here in an artist's rendering. |

The extraordinarily preserved hadrosaur, or duck-billed dino, still had much of its tissues and bones intact, encased in an envelope of skin.

Research into the dinosaur's remains may further scientists' understanding of how the ancient creatures' skin appeared and how quickly they moved, said team leader Phillip Manning of the University of Manchester, a National Geographic Expeditions Council grantee.

"This specimen exceeds the jackpot," Manning said.

Dakota was about 35 feet (12 meters) long and weighed some 35 tons, but the dinosaur was no slowpoke, according to preliminary studies.

|

| ©National Geographic |

| The skin of a duck-billed dinosaur pokes out of the soil at Hell Creek Formation in North Dakota. |

Much of Dakota's fossilized skin has maintained its texture, allowing scientists to map it in 3-D and get a better picture of how duck-billed dinosaurs may have appeared.

"There seems to be a variation in scale size that might possibly correlate - as it does in modern reptiles in many cases - with changes in color," said Phillip Manning, a paleontologist at Britain's University of Manchester and a National Geographic Expeditions Council grantee.

"And there seems to be striping patterns associated with joint areas on the arm," he added.

|

| ©National Geographic |

| Field paleontologists drill under a mummified dinosaur's ten-ton body block, now separated from its tail. |

The odds of such an intact dinosaur being found are extremely slim, Manning said. The dinosaur body must have somehow escaped predators, scavengers, and degradation by weather and rivers, he said.

What's more, a chemical process must mineralize the tissue before bacteria eat it, and then the fossil must withstand the test of geologic time.

"What usually would have been wiped out by the decay process - the mineralization [of Dakota's body] has been so rapid that it is trapped and preserved," Manning said.

So far the high-resolution scans, partially funded by the National Geographic Society, have revealed that the backside of the 67-million-year-old duck-billed dinosaur was 25 percent larger than previously thought.

A larger, more muscular rear end means that the animal had powerful legs, according to British paleontologist Phillip Manning, who is leading the examination.

"Our models confirm this hadrosaur would have had potential to run faster than T. rex," Manning said. Preliminary calculations suggest that the dino could run 28 miles (45 kilometers) an hour, while T. rex topped out at about 20 miles (32 kilometers) an hour.

"It's rare to find an articulated skeleton, and even more so to find one with fossilized soft tissue," said Michigan State University zoologist Peggy Ostrom, an expert in ancient proteins who was not part of the Dakota team.

"If such finds show extraordinary preservation, they tempt us to wonder about the possibility of finding [unfossilized] biomolecules that might be remnants of the ancient organism."

The discovery, excavation, and analysis of the mummified dinosaur is featured in Dino Autopsy, which will premier on December 9 at 9 p.m. EST/10 p.m. PT on the National Geographic Channel.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter