"Conical pots of this type have been recognized quite widely in the Roman Empire, and in the absence of other evidence, they have often been called storage jars," said co-author Roger Wilson of the University of British Columbia. "The discovery of many in or near public latrines had led to a suggestion that they might have been used as chamber pots, but until now, proof has been lacking."

Comment: This discovery just demonstrates how patchy our understanding of life in the past really is.

Archaeologists can learn a great deal by studying the remains of intestinal parasites in ancient feces. Just last month, we reported on an analysis of soil samples collected from a stone toilet found within the ruins of a swanky 7th-century BCE villa just outside Jerusalem. That analysis revealed the presence of parasitic eggs from four different species: whipworm, beef/pork tapeworm, roundworm, and pinworm. (It's the earliest record of roundworm and pinworm in ancient Israel.)

Other prior studies have compared fecal parasites found in hunter-gatherer and farming communities, revealing dramatic dietary changes, as well as shifts in settlement patterns and social organization coinciding with the rise of agriculture.

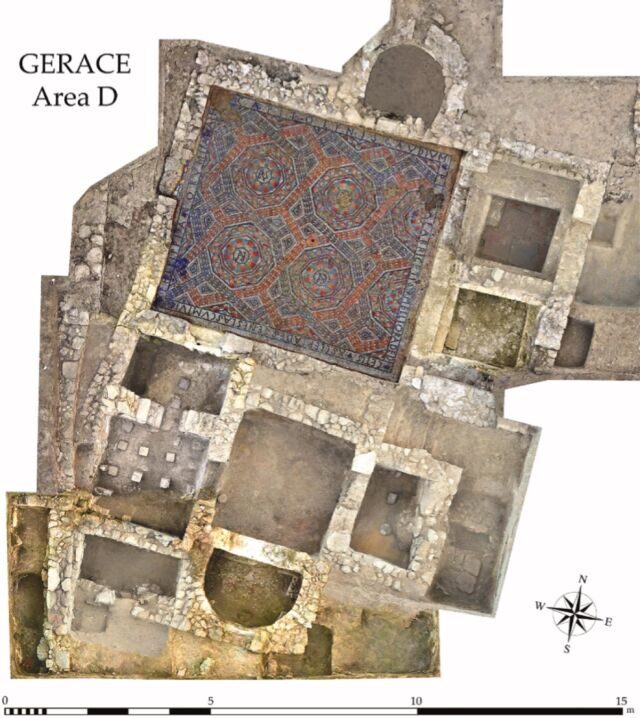

This latest study concerns a ceramic pot excavated at the site of a 5th-century CE Roman villa at Gerace, a rural district in Sicily. The site was discovered in 1994 and was explored a bit in 2007, but the most extensive excavation has been done since 2013, over the course of six campaigns. Archaeologists uncovered a modest villa featuring decorative mosaic pavements and a detached bath house with similar mosaic and marble ornamentation. There is also a large storage structure and kilns.

The villa was known as "the estate of the Philippiani," based on a mosaic found in the bath house's cold room (frigidarium). Per the authors, the baths were badly damaged by an earthquake sometime in the second half of the 5th century, and repair attempts were ultimately abandoned. The baths were stripped of most useful materials and then filled in.

The pot in question was found at the bath house site in 2019, just outside one of the warm rooms (tepidarium), and it was likely tossed there during the stripping and filling-in period since it was broken. Its size (about 12.5 inches high and 13 inches in diameter at the rim) is just right for a chamber pot. The authors surmise that the user could have sat directly on the pot, or the pot could have been placed under a wickerwork or timber chair.

The pot also had crusty mineralized layers (concretions) on its interior, and it was this substance that the team collected for further analysis. The process was a bit more complicated than analyzing sediments collected from, say, an ancient latrine, in which parasite eggs have been found in past studies. The authors had to separate any preserved eggs from the concretion matrix, which they achieved with the help of diluted hydrochloric acid.

The Cambridge team then analyzed the samples under a microscope and confirmed the presence of whipworm eggs — the most common species found in ancient Roman contexts. These are human parasites that thrive in the lining of the intestines, so their eggs get mixed in with human feces. It's the first time that parasite eggs have been found in the concretions inside a Roman ceramic pot and is a strong indicator that it was likely used as a portable toilet.

"This pot came from the baths complex of a Roman villa," said co-author Piers Mitchell, a parasite expert at the University of Cambridge. "It seems likely that those visiting the baths would have used this chamber pot when they wanted to go to the toilet, as the baths lacked a built latrine of its own. Clearly, convenience was important to them. Where Roman pots in museums are noted to have these mineralized concretions inside the base, they can now be sampled using our technique to see if they were also used as chamber pots."

DOI: Archaeological Science Reports, 2022. 10.1016/j.jasrep.2022.103349 (About DOIs).

Now some boffs 🤪 🤪 from the University of British Columbia are suggesting that for all the Romans advancements, they preferred to shit in a terracotta pot