One of the things I have found quite mind-blowing while working with seniors is how few people are concerned about their privacy and either refuse to consider the risks they face using tools like Google products or Microsoft's latest OS, or else rationalise it with the hoary old chestnut - if you're not doing anything bad, you have nothing to worry about - which is just wrong on so many levels.

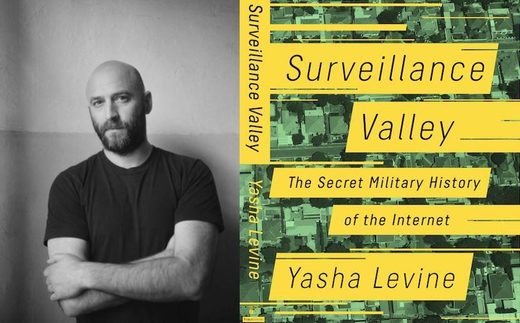

Recently I have been reading an enlightening book by Yasha Levine called Surveillance Valley, which is basically a history of the internet that explains how it emerged from a Pentagon ARPA project (now DARPA - Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) to facilitate data-sharing between military/intelligence agencies so they could improve their counterinsurgency programs against targets both inside and outside the USA. Levine also details how every breakthrough in technology that enabled the internet as we know it today was either spun out of ARPA research or was directly (and primarily) funded by such.

I highly recommend you acquire a copy of Surveillance Valley and read it. Levine will shatter any illusions you may still hold about how the internet was ever going to be a tool of individual freedom against government.

I want to focus on just one case study Levine explored - Google, whose operations today effectively comprise 25% of the entire internet. Before reading the book, I thought I had an appreciation of what Google was up to, and how incredibly intrusive it is when it comes to personal information, but actually I didn't know the half of it.

Google was started by two students from Stanford University, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, who wanted to create a better search algorithm, an algorithm with predictive elements that could generate meaningful search results, rather than just long lists of largely irrelevant links.

Page grew up around computers; his father was a NASA researcher, and his mother taught computer programming at Michigan State University. He grew up programming and after finding inspiration in the story of Nikola Tesla, he fed a desire to invent things and change the world. As Levine puts it, "Stanford University and a research program funded by DARPA would allow him to achieve his dreams."

After WW2, Stanford was the elite engineering university closely linked to the US military-industrial complex. There was a huge university industrial park which became the hub for computer and microprocessor development. In that park there was also a branch of DARPA. Awash with military cash and cybernetic utopianism, Stanford later became the epicenter of the dot-com boom. And in this environment, Page started a computer science PhD program in 1995. Seeking a project for his dissertation, he finally settled on internet search. Contemporary search algorithms were very primitive but had attracted piles of cash - think Yahoo, AltaVista and Excite - so finding a better way to search would be challenging but financially rewarding.

Page's graduate advisor, Terry Wingrad, came from a background of research with ARPANET and the Digital Libraries project, sponsored by civilian, military and law enforcement agencies. ARPANET was the original 'internet', first tested in 1969 between Stanford and UCLA. The Libraries project had a civilian mandate but the intelligence agencies wanted to be better able to access the digital trail people left on the internet with diaries, blogs, forums, photographs and emails. So this project was a good fit and Terry Wingrad was an appropriate mentor. When Page finally published his first research paper, it was marked "funded by DARPA."

Sergey Brin was the polar opposite to Page. Outgoing and flamboyant, at Stanford he focused on data mining, building computer algorithms to predict what people would do based on their past actions. And indeed, behavioural data mining would prove to be a core Google foundation.

The key factor for Page and Brin was PageRank. They developed a way to rank every page on the internet based on the number of times it was linked to other pages. Some links were worth more - a link from a national newspaper was more powerful than a link from a personal homepage. In the end the rank of any given webpage was the sum total of all the links and their values that pointed to it. As a consequence, Google manifested explosive growth and became the default search engine for the internet - and even had a verb named after it.

One part of the drive behind the Google experience was predictive search - the ability to interpret what you want from a search term, based on what you have done before, websites you have looked at, and search terms you have used. In order to make that work effectively, Google needs data - your data, and the more data the better.

And this is where things start to get spooky. The impetus driving everything Google does, including the products Google offers, is data collection for future data mining. In the beginning, Google collected your searches. Then, by using tracking cookies, a small piece of code placed on your machine, Google was able to see where you went after you left the search engine or the site you found using the search engine. The more data it gathered, the better 'psychographic' picture Google had of you and your online habits.

But search terms and your trail on the internet wasn't enough. And so we saw the launch of the 'free' email service Gmail in 2004. In data gathering terms, this was pure genius. In order to use the service, you gave Google permission to scan all of your emails. Think about that. You gave Google the right to read all the emails you send and receive, all the attachments, all the documents, all the invoices, all the photos etc. Everything in your life that comes by email was suddenly available for Google to mine and that data then became theirs.

What better way to connect browsing data from millions of people, aside from being the default search engine, than to offer people a free browser. And so we saw the birth of Google Chrome, probably the most used browser on earth.

Then came Google Calendar and Contacts. Same story. You gave Google access to everything you do every day and to all the people you know, whether through business or your personal life. And still that wasn't enough. With the purchase of Android, Google extended its reach even further into your life. Through your phone, Google could now track who you called, who you texted, what was in the texts, where you went (via the location feature), the apps you use, the apps you own. And did I mention the Google online apps - their take on Microsoft Word, Excel and PowerPoint. (By the way, don't feel virtuous if you use an Apple phone. You are in just as bad a place. When it comes to data harvesting, Apple is as rapacious as Google)

The cherry on the cake for vacuuming up even more of your data comes courtesy of Google Drive. Google will give you 15 Gb of online storage to store all your electronic data and records. It's free, folks. Give us your stuff and we will keep it for you on Google Drive. If it is deleted from your home system, you can get it back from us. We are the good guys and we will look after your data, for free. And you can share it across all your devices. Isn't that so very convenient?

Can you imagine the amount of detailed data that Google has on multiple millions of people worldwide - a virtually complete picture of their likes, dislikes, habits, hobbies, indiscretions, business matters, work history, sexual affairs, sexual orientation, friends, enemies, travel habits, movie and book preferences, political leanings, financial status...

Google has said from the beginning that it is only using this data to better target users with advertising, although they don't boast too loudly that they're selling the data to advertisers and making a fortune from users' personal information. But recall where these people started from, who funded them, and the close and profitable relationship Google has with the US government in general and the military-intelligence 'community' in particular. Then recall the NSA's PRISM program, as revealed by Edward Snowden. Among the Snowden documents was tangible evidence that the largest, most respected internet companies - Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, Microsoft - had worked secretly to funnel data on hundreds of thousands of users to the NSA. And they were VERY keen that you didn't know about it. And according to the agreements you made when you began using these products, the internet behemoths own that data and can use it in any way they want, including giving it to the NSA and hence the entire shower of sordid spooks running civilization into the ground.

In the end, there's no such thing as online privacy. Not absolute privacy anyway. But what you can - and should, in my opinion - do if you are a consumer of Google products - Gmail, Chrome, Android, Calendar, Contacts, Earth, Maps - and you want to drastically reduce the data siphoning are the following:

- Change your browser. Don't use Chrome or a chromium-based browser. Firefox is a viable alternative and the Mozilla foundation at least tries to err on the side of privacy.

- Change your search engine. Don't use Google as your default search engine. Duckduckgo and Startpage are two good alternatives which don't copy and store your data.

- Don't use the Gmail suite of products - mail, calendar, contacts, tasks. There are many email services - Fastmail, Protonmail, Startmail, Mailfence and many others - who do not pretend to offer a free service and then vacuum your details. You will have to pay a yearly fee to use them but, let's be honest, you are either going to pay money, or sacrifice your privacy - your choice. And don't just change to the Microsoft equivalent; all the same privacy issues exist in that ecosystem as well.

- Change your cloud storage provider - avoid cloud offerings from Microsoft, Google, Apple, Amazon and any of the other internet behemoths.

Reader Comments

But don't get fooled - with other browsers, search engines, or cloud providers, you don't hide your data from the NSA and the FVEY. If you don't want them to know it, don't put it on the net. Ever.

1- Use other Operating system Specially Linux (this is maybe one of the most important suggestions)

2- If using Firefox, install Ublock Origin Plugin

3- ALWAYS use a process Manager to see the state of processes and the state and use of your bandwidth... (specially the OUTGOING one - extreme useful)

4- If in Firefox (or any browser) DISABLE Search Suggestions (prevent you of being Deep Data Mined)

5- Keep Cookies until your browser is closed

6- Always Use Tracking Protection to block known trackers (very powerful) in your browser settings

7- From time to time Clean and Block (if necessary) websites that have requested to access your Microphone, Camera and Location.

With that measures you can warrant the MINIMUM of safety and security.

But remember The NSA/ECHELON combo will NEVER SLEEP to get your Metadata or Data.

And you confuse tracking by companies and websites with spy agency eavesdropping. The latter tap your communication at the provider, who happily collaborates.

1- Right there is no 100% secure OS, but at least in Linux you have tools (If you are eager to learn) that allow you to mitigate or make difficult the eavesdropping of NSA/ECHELON. Windows/MacOSx are far more compromised than you think.

2- There is no confusion at all... the more you prevent TRACKING in any form the better you difficult things to the Spy agencies.

Remember as Snowden pointed out in the past The spy agencies BIG business is collecting your METADATA and to do that a mixture of tracking by "companies and websites" married to the tapping of communication at the ISP/Transatlantic level is necessary...

The name of the game of the ECHELON (Five Eyes club + 1 (Israel Mossad)) is Multi-modal Data Mining, cross referencing anything you do with electronic equipment... in or out of the Net.

I remember 20 years ago when I talked about ECHELON almost Everybody will laugh in front of my face. Guess what???

Reality catches up with them now... (google, Oracle, Yahoo, Facebook, Tweeter et al) are just Tentacles of the same monster, namely ECHELON (Five eyes) + 1 (Israel Mossad)

Remember that management engine uses The MINIX (Andrew Tanembaun) Operating System onboard the i5/i7/Xeon processors

But there are ways to mitigate it...

But that is above the level of discussion presented in the above article...

My current challenge has been to de-Goog my Android phone as much as possible (short of rooting it). There are substitute apps for: SMS/texting, photo handling and storage, keyboard, browser, phone (dialing, address book), app store (F-Droid), ringtones, and missed notifications.

It takes rather a lot of effort and is not as easy as it used to be when we trusted everything.

But are they updates?