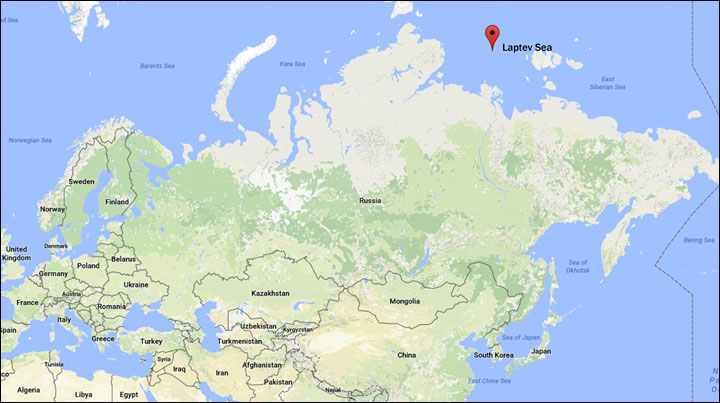

The findings come from an expedition now underway led by Professor Igor Semiletov, of Tomsk Polytechnic University, on the research vessel 'Academic M.A. Lavrentyev' which left Tiksi on 24 September on a 40 day mission.

The seeping of methane from the sea floor is greater than in previous research in the same area, notably carried out between 2011 and 2014.

'The area of spread of methane mega-emissions has significantly increased in comparison with the data obtained in the period from 2011 to 2014,' he said. 'These observations may indicate that the rate of degradation of underwater permafrost has increased.'

Detailed findings will be presented at an international conference in Tomsk on 21 to 24 November. The research enables comparison with previously obtained data on methane emissions.

Dr Semiletov and his team are paying special attention to clarify the role of the submarine permafrost degradation as a factor in emissions of the main greenhouse gases - carbon dioxide and methane - in the atmosphere.

The team are examining how the ice plug that has hitherto prevented the exit of huge reserves of gas hydrates has today 'sprung a leak'. This shows in taliks - unfrozen surface surrounded by permafrost - through which powerful emissions of methane reach the atmosphere.

Scientists are eager to determine the quantity of methane buried in those vast areas of the Siberian Arctic shelf and the impact it can have on the sensitive polar climate system.

'This is the first time that we've found continuous, powerful and impressive seeping structures, more than 1,000 metres in diameter. It's amazing. Over a relatively small area, we found more than 100, but over a wider area, there should be thousands of them.'

In 2013, his research partner Natalia Shakhova, a scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, reported in journal Nature Geoscience, that the East Siberian Arctic Shelf was venting at least 17 teragrams of the methane into the atmosphere each year. A teragram is equal to 1 million tons.

'It is now on par with the methane being released from the arctic tundra, which is considered to be one of the major sources of methane in the Northern Hemisphere,' she said. 'Increased methane releases in this area are a possible new climate-change-driven factor that will strengthen over time.'

Methane is a greenhouse gas more than 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide. On land, methane is released when previously frozen organic material decomposes.

Under the seabed, methane can be stored as a pre-formed gas or as methane hydrates. While the subsea permafrost remains frozen, it forms a cap, trapping the methane beneath. But holes are now developing through which the methane escapes.

In 2014, the Russian professor said there were 500 abnormal fields of methane emissions.

The same year he explained: 'Emissions of methane from the East Siberian Shelf - which is the widest and most shallow shelf of the World Ocean - exceed the average estimate emissions of all the world's oceans.

'We have reason to believe that such emissions may change the climate. This is due to the fact that the reserves of methane under the submarine permafrost exceed the methane content in the atmosphere is many thousands of times.

'If 3-4% from underwater will go into the atmosphere within 10 years, the methane concentration therein (in the atmosphere) will increase by tens to hundreds of times, and this can lead to rapid climate warming. This is due to the fact that the greenhouse effect of one molecule of methane is 20-30 times greater than one molecule of CO2.'

The new expedition was organised by the Laboratory of Arctic Research in Pacific Oceanology Institute of the Far Eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences in cooperation with Tomsk Polytechnic University (TPU), the Institute of Oceanology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, and was funded by the Russian Government and the Russian Science Foundation.

The results of the expedition will be discussed at the international conference, which will be attended by scientists from 12 universities and institutes of Russia, Sweden, Netherlands, Great Britain and Italy.

Will it be enough to stop the "new ice age" (or rather the end of interglacial)? If so that's unfortunate, because the crazy religion of "human driven climate change" and anti-carbon dioxide regulations will continue unhindered