Led by Hans-Ullrich Wittchen, a psychologist at the Technical University of Dresden in Germany, the three-year study covered the 27 countries in the European Union (EU) as well as Switzerland, Norway and Iceland. The researchers found that the most common disorders are anxiety, insomnia and depression, which account for 14%, 7% and 6.9% of the total, respectively.

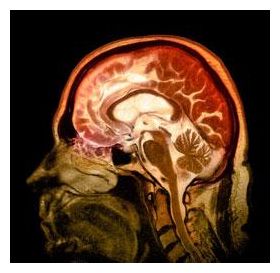

The researchers originally aimed to study all disorders of the brain, split into two major categories: mental or psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia, and neurological diseases such as stroke, multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's disease. Ultimately, they weren't able to estimate the combined prevalence, because so many of them occur together. So Wittchen says the true figure is likely be "considerably larger" than 38%.

The cost of stigma

The researchers were, however, able to estimate the combined burden of the two types of disorder. Taken together, mental and neurological diseases are Europe's largest disease burden, in terms of life-years lost to death or disability and of productivity and health-care costs. The most debilitating disorders were depression, dementia, alcohol use disorders and stroke, which together account for more than 10 million life-years lost to ill health or death.

In a previous report also led by Wittchen,2 health-care costs to the EU for mental disorders were estimated at around €277 billion (US$394 billion). In October, Wittchen and his colleagues will publish a report estimating the present cost of these diseases to governments. Wittchen hints that the true figure, with the addition of new conditions, age ranges and countries, could be more than double the 2005 estimates.

But when it comes to treatment, especially for psychiatric conditions, the situation is "unusually deficient", says Wittchen, even in countries with good healthcare systems. "It's very rare that you get treatment in the year after onset."

This is partly because the conditions themselves are complex and difficult to treat. But, Wittchen says, the stigma attached to mental disorders is also to blame. "Most people have the feeling that once you have a mental disorder you have it for the rest of your life," he says, but many of these disorders can be treated.

Neglecting to treat one mental disorder can easily lead to another later on, Wittchen says. Anxiety disorder, for example, often leads to depression in later life. David Nutt, a neuropsychopharmacologist at Imperial College London, agrees that rapid treatment is key. "If we can get in early we may be able to change the trajectory of illness," he says.

Mind matters

This kind of synthesis of the burden of mental and neurological conditions hasn't been done before. "It's a highly impressive study, and it's unique in scope," says Nutt, who was not involved in the study.

In 2008, the World Health Organization estimated that brain disorders account for about 13% of the global disease burden,3 a greater burden than cardiovascular diseases and cancer. The World Mental Health Survey, published in 2008 and covering 28 countries, estimated that one in three adults suffers from a mental disorder.4 And a new study from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, pulled together data from surveys to reveal that 6.8% of adults had moderate to severe depression.

The new report is an update on a 2005 paper2 that estimated that 27% of the EU population was affected by mental disorders each year. The higher figure resulted from the addition of 14 previously excluded disorders, many of which affect children and the elderly. But the frequency of mental disorders has probably not gone up substantially, Wittchen says. "There's no evidence for changing rates."

References

- Wittchen, H.-U. et al. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 655-679 (2011).

- Wittchen, H.-U. & Jacobi, F. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 15, 357-376 (2005).

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update (WHO, 2008).

- Kessler, R. C. & Ustun, T. B. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys: Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Mental disorders, or sane reactions to the problems of this world? Show me someone who is not affected by the joblessness, warfare, toxic food, etc., and you've shown me someone who is either rich or insane A little bit of anxiety or depression is a healthy response that will hopefully lead to some fundamental changes.