The carving from the Guatemalan site of Naachtun likely dates to the end of the fourth century, when Mayan dynasties were being established.

|

| ©University of Calgary |

| A close-up of the carving. |

"This woman was obviously a very important figure," said Kathryn Reese-Taylor, director of the University of Calgary team that made the discovery in the tropical forest of the Yucatan peninsula earlier this year.

For scholars, the discovery raises new questions, such as were women founders of dynasties and were all patron deities male?

Three lines of evidence show the importance of the two-metre-high find:

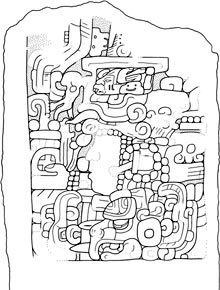

Researchers don't know if the woman was a historic or mythological figure. The glyphs on her headdress, which is typical of royalty, name her as Lady Partition Lord or Lady Partition Flower.The early portrayal of a female on a stela or stone carving in itself is significant. Until now, archeologists have found women from this time period named in texts but not depicted. Maya attacked and targeted historic stela by chipping off the inscriptions, as is the case for this monument. The monument was reverentially reburied by the Maya in an ancient building after the city and inscriptions were attacked. Reburial is usually reserved for founders or kings.

The limestone stela has unique style. The woman's body is missing and the image focuses instead on only her head and headdress, said Julia Guernsey, a professor of Precolumbian art history at the University of Texas at Austin and a member of the team.

The elaborate headdress features a reptilian creature as its main element, with waterfowl coming off the top, feathers and a sacrificial dish.

|

| ©University of Calgary |

| Drawing of Stela 26. |

"It's much bigger than anything Carmen Miranda ever wore," Reese-Taylor said.

The stela doesn't follow the usual style of monuments from the time or later, which suggests there may have been room for independent art styles before conventions were established on portraying women, she added.

The find has been given to the government of Guatemala and was presented at a symposium in July.

The research is sponsored by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the University of Calgary, universities in the United States and Australia, and private funders.

Comment: Earth goddess or Mayan Nefertiti?