OF THE

TIMES

Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well... You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect...

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.

let's not forget......Home EC. All the guys I took Home Ec with in high school loved it. They learned to sew buttons on, hem their pants and they...

I watched a Documentary about a year ago which highlighted wealthy Israelis flying to China to get organs harvested from the Falun Gong. The...

Thanks JennB for your insight and humour, a firestorm of comments, with more to arrive, I suspect. Great Work!

I remember the acronym of a well appreciated commentator (some may remember him)...NFC...No further Comment. Rowan....RIP

What is important here to my mind is, the very foundation of the US constitution...as a test case for the west. First amendment right of the US...

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

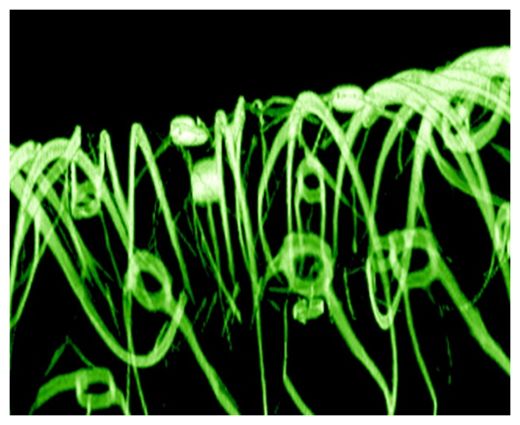

little nano fibers poking out of skin..hmmmm