When I first heard how they were planning to get more than a tonne of nuclear- powered kit down on to the Martian surface in one piece I thought they were joking.

'You're going to use parachutes?'

Yup.

'Then retro-rockets?'

You betcha.

'Fine, but then you are going to dangle the thing on four steel cables, lower it gently to the ground from a hovering rocket-powered mothership, those cables are going to automatically detach then the mothership is going to scoot off and crash out of harm's way. And all this with absolutely no control from Earth?'

You have understood correctly.

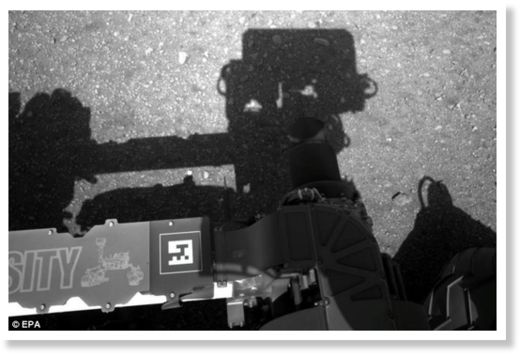

Well, sceptics be damned. The Skycrane system worked perfectly and Curiosity is now down, home and dry, revving up its nuclear-powered motors to go where no robot has gone before (specifically, the mother of all geological field trips involving, it is hoped, a climb up a three-mile-high Martian mountain.

Depending on what it finds, it is quite probable that we will not see the likes of Curiosity again, at least not for many decades. It is true that today NASA has announced funding for a probe called InSight, to be launched in 2016, but this is a cheap-and-cheerful mission not the full-fat effort as typified by Curiosity's $2.5bn price tag.

So what are they hoping that Curiosity will find? Officially, the mission's chief objective is to find whether Mars ever had conditions conducive to the existence of life. Specifically, by sniffing, peering at and zapping with its now-famous laser gun a whole suite of Martian rocks, NASA scientists hope to use Curiosity to find out whether the Red Planet was once, as most planetary astronomers believe a warmer, wetter place than it is today.

But what Curiosity is NOT designed to do is actually search for life. It is possible that one of its cameras may uncover signs of fossil microbes or even larger organisms preserved in the Martian rocks. It is not completely impossible that it could yet stumble upon some sort of extant living organism, perhaps a suspicious colored coating on a Martian rock or some-such.

But Curiosity is not equipped with the sort of laboratory kit that could sniff out living Martian bugs in the soil. And to some that is strange.

In New Scientist this month it was reported that Gilbert Levin, a former NASA scientist, is restating his claim that the mission he worked on, Viking, did discover life on Mars way back in the 1970s. Levin is a bit out on a limb here (most of his colleagues disagree with him) but I think he may - just may - have a point.

The two Viking landers were static probes which arrived on the surface of Mars in the summer of 1976. What they were equipped with - and Curiosity is not - was a series of experiments designed to see if living bugs existed in the Martian soil.

The 'labelled release' experiment was quite simple. Some Martian soil was scooped up, and mixed with a nutrient broth (a mixture of sugars and water and other chemicals) containing radioactive carbon. The idea was that if the Martian bugs 'ate' their soup then they would emit puffs of radioactive carbon dioxide, showing that they had metabolised the nutrients. Much to everyone's surprise, not only did the soil give off CO2, that CO2 was also found to be radioactive.

But then a second experiment, designed to find carbon-based molecules in the Mars soil (the sort of molecules which would be found in any putative microbes) found none. The positive result from the labelled release experiment was declared null and void after the second set of results came in.

That is the consensus view. But Levin insists there is a problem. It turns out the carbon-detectors aboard the Viking landers were not sensitive enough to detect organic molecules even in Earthly soil samples known to contain microbes. Levin insists his positive result stands and furthermore that if Curiosity discovers carbon compounds in the Martian soil (which it IS equipped to do) we can retrospectively date the discovery of life on Mars back to the Bicentennial Year of 1976, way back when Jimmy Carter was in the White House.

It would be irony indeed if a 21st Century robot that in nearly every way is hugely superior to its Viking forbears were to end up making the discovery of the century - by proxy. Many scientists and Mars enthusiasts - myself included - have thought for a long time that it is a bit odd that after Viking NASA has seemed to be studiously NOT looking for life on Mars. I can imagine why. Aliens, even microbes, have the whiff of the fringe about them and until recently NASA liked to shy away from the whole question of extraterrestrial biology altogether. But the existence, or not, of life elsewhere is surely the most important question that agencies like NASA should be tackling.

Curiosity is a marvellous beast. I am hugely glad it is down in one piece and wish it every success. I am sure we will not be disappointed. Especially if it finds those carbon compounds. Perhaps if it does the boffins at JPL might finally break the rules and open a bottle or seven of champagne - and invite Gil Levin round to join the party.

In the "alternative reality" community, there has been so much more water under the bridge!

It's almost like: Will the others ever catch up?

Not that our own data is pure. But the basic facts come at us from so many different sources! They couldn't all be lying. There isn't even a motive to do so, as far as I can tell.

I just wish that more people who know the score would tell the truth! (Tweet #GUYTTT)