Now, the deaths of two children have triggered the closure of Lily Lake, a 36-acre pool in the city of Stillwater, Minnesota. But Lily Lake isn't the only body of water health officials are worried about; N. fowleri is more common than most people realize, and its appearance in Minnesota indicates that it may actually be spreading. io9 spoke with epidemiologist Jonathan Yoder, who tracks N. fowleri for the CDC's division of parasitic diseases, to find out what's being done to address the deadly infections.

The prospect of picking up a brain-devouring parasite at your local lake or pond is pretty terrifying if you think about it. Unlike a neti pot, which involves going out of your way to drain your sinuses by actively pouring water up your nose, few people think twice about the risks of swimming in a public lake.

"You can't keep your kids out of lakes, you know," Jim Ariola told the New York Daily News. He's the father of nine-year-old Jack Ariola-Erenberg, who died last Tuesday of the rare brain infection. "Who all has a pool? When I was little, I swam in that lake because I had hockey camp right there at Lily Lake."

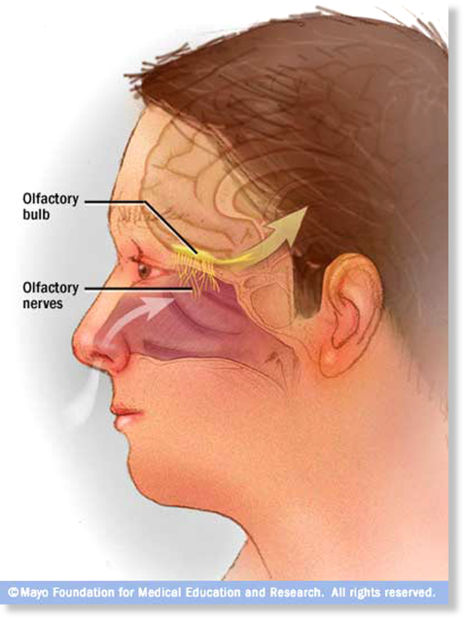

The first child in Minnesota to die from N. fowleri at Lily Lake was seven-year-old Annie Bahneman, who was infected in the summer of 2010. Doctors think she was exposed to the parasite while practicing handstands in the water. The amoeba makes its way to the brain via the olfactory nerve, which it accesses when water is forced up the nose.

That the two incidences of N. fowleri infection at Lily Lake are the only known cases in Minnesota's history highlights the challenges that the amoeba poses as a public health issue, and points to an unsettling reality: our scientific understanding of the parasite - from the extent of its distribution to its mechanism of infection - is actually quite limited.

For example, while current screening methods can tell us whether or not N. fowleri is living in a water supply, CDC epidemiologist Jonathan Yoder told io9 that researchers have no good way of detecting how much of the parasite is actually present.

Granted, one might expect that the detection of any trace of the parasite would be reason enough to avoid a body of water, but the fact of the matter is that N. fowleri is much more common than people realize.

"If you look in enough locations, particularly during the warm weather months... there's a good chance of finding it," explains Yoder. He continues:

The most extensive testing [for N. fowleri] in the U.S., that I'm aware of, was done back in the late seventies and early eighties by the EPA... They surveyed [dozens and dozens] of lakes in Florida, in Georgia, looking for Nigleria fowleri, and found it - if I remember correctly - in around half of the lakes during the warm weather months.Yet despite the parasite's prevalence, only around 125 people are known to have died of N. fowleri infection in the U.S. since it was formally identified fifty years ago.

In other words, says Yoder, "we can find it in a lot of places, where lots of people swim, but there don't appear to be infections there - or at least none that we're aware of." Furthermore, the inability to quantify the N. fowleri means there's no way to tell if quantity is in any way related to how regularly people are becoming infected. And that creates an interesting challenge, says Yoder, from a public health standpoint: when N. fowleri prevalence is high, but infection rates are low, what do you tell people when you find it? In fact, a more timely question may be: what do you tell people when you find that it's spreading?

The presence of N. fowleri in waters as far north as Minnesota may be evidence that the range of the parasite is expanding on account of climate change. According to Minnesota Public Radio:

For the Naegleria fowleri amoeba to grow, the water has to warmed above 85 degrees. It even thrives in hot spring water. It's considered endemic in the southern United States and has been reported in Australia and Pakistan, as well.The fact that rates of infection are rare, even in waters where N. fowleri are known to reside, helps explain why Lily Lake was allowed to remain open following Bahneman's infection in 2010, but the lake was closed shortly after Ariola-Erenberg's death, and is now marked with signs reading "Danger" and "Stay out of the water." It won't reopen for the remainder of the season, and the lake's future beyond that remains unclear.

A paper on the 2010 case in Minnesota said that infection was more than 500 miles further north than any previously reported case, and warned that warm weather and climate change could expand the amoeba's geographic threat. [emphasis mine]

Yoder says that the CDC is working to develop tests that can accurately quantify the number of N. fowleri present in a body of water, but the accuracy of these tests may prove irrelevant; "animal models," he explains, "show that as few as one or two amoeba [in the nose of a mouse] can cause infection." At numbers that low, being able to put a number on how many of the parasites are living in a body of water may ultimately tell us very little about whether that water is safe or not. "We just don't know enough about the ecology of Naegleria fowleri," he says.

So what can you do to protect yourself? Yoder suggests a mindful, well-measured approach:

"We'd like people to be aware that this exists," he explains, "and understand that there is a low level of risk any time they go into a warm body of fresh water, particularly during the hot summer months." If you do go in the water, Yoder recommends not submerging your head, or - if you do - to hold your nose, or wear a nose clip. Even though these precautionary measures have not been studied scientifically, he says, "in some ways they make common sense; anything you do to reduce the risk of water being forced up your nose, probably reduces the risk of infection."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter