© Unknown

This is an excerpt from reporter Scott Johnson's

blog, which focuses on the effect of violence and trauma on the community.

Why is it that when we hear a rumble, the sound of an earthquake, say, we don't try to locate the sound, but we immediately try to get away? Or, if we hear a high-pitched sound of distress, we try to locate it because, well, someone close to us might be in pain? Did you know that the muscles in your middle ear are linked in your brain stem to the muscles that control your upper face? Or that when you see people's eyes droop during a conversation, they're probably not hearing a word you're saying, or not well?

Broken down into their most basic components, our neural systems are modulated on two systems: safety and novelty. Safety is the more important of the two; it's the most important thing for every one of us. Novelty is also important; it helps our brains to grow, but novelty can't be experienced without safety. And yet we require novelty to become fully human; we can't expand as living beings without rich lives.

This idea and the complex questions that flow from it lie at the heart of one of the most intriguing and exciting ideas in the world of neuroscience, psychology and the study of complex psychiatric disorders and trauma. It's called polyvagal theory, and it was crafted by Dr. Stephen Porges, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and the director of the Brain-Body Center.

The theory is complex, and I won't be able to do it any measure of justice in this short space, but it is worth exploring, and

links to his work are available here.Porges believes that human beings have evolved in such a way that social behaviors, emotional disorders and the ways we respond to stress, trauma and psychological distress are deeply rooted in our biology, that our behaviors are more "hard-wired" than previously thought.

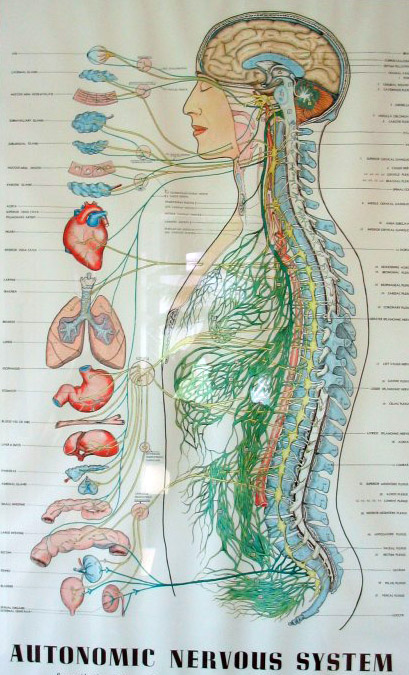

For instance, Porges says that the neural pathways of the body's nervous system are closely connected to the muscles in the face. The muscles that control the heart and lungs are tied to the muscles that control how the face operates, how it looks when we interact with each other.

Here's Porges in a 2006 interview in nexuspub. com: "We forget that listening is actually a 'motor' act and involves tensing muscles in the middle ear. The middle ear muscles are regulated by the facial nerve, a nerve that also regulates eyelid lifting. When you are interested in what someone is saying, you lift your eyelids and simultaneously your middle ear muscles tense. Now you are prepared to hear their voice, even in noisy environments."

What does that mean for you and me? Well, for people with high levels of anxiety, or stress or even post-traumatic stress disorder, this can be very useful information.

Here's Porges again: "The concept of safety is relative. You and I are sitting in this room together and nothing appears to threaten us. We feel safe here, but it may not feel safe to a young woman with panic disorder. Something in this environment, which is safe for us, might trigger in her a physiological response to mobilize and defend. But this approach doesn't work very well with social engagement behaviors, because they appear to be driven by the body's visceral state. Our current knowledge based on the polyvagal theory leads us to a better approach. Thus, to make people calmer, we talk to them softly, modulate our voices and tones to trigger listening behaviors, and ensure that the individual is in a quieter environment in which there are no loud background noises."

This may seem to make intuitive sense. But it's not always obvious to the listener. People who are traumatized, for instance, or those with bipolar or somewhere on the autism spectrum -- those people, in certain states, may be simply unable to distinguish human voices from the kind of background noise you'd hear in a shopping mall or at a concert.

Porges says his theory also supports the notion that we can potentially have a lot more control over our own emotions and our responses to others by breathing. Why? Because controlling breath exerts a powerful influence over the "vagal" nerve that connects our faces, lungs, heart and muscles.

"Breathing exercises the vagal (nerve)," Porges said at a recent conference I attended. "The longer the phrase, the calmer you are. The shorter the phrase, the angrier, more stressed. Breath is extraordinarily powerful in shifting the neural platform upon which we interact with the world."

What's the point, then? The idea is that by paying attention to your own body, your breath, your face, you can help regulate yourself to become less of a hostage to the powerful grip that fear and trauma can hold on your body.I'll give Porges the last word: "The point of these strategies is to create an environment in which we no longer need to be hypervigilant, and to allow us to participate in the life processes that require "safe" environments. Social engagement behaviors -- making eye contact, listening to people -- require that we give up our hypervigilance."

Read more of his stuff on the blog!

Reader Comments