Just a year before, Di Martino of the Italian National Institute for Astrophysics in Turin, Italy, and colleagues had written their names on paper, placed it inside an empty bottle and thrown it into the crater. The reason? They were the first team to visit the site of a huge meteorite impact 5000 years ago. Few craters on Earth are so perfectly preserved. "We realised we were in front of a true rarity," recalls Di Martino. The team's analysis of the fragments they collected will appear in the 13 August issue of Science.

Though the meteorites were still there, ominously the bottle had disappeared. "Unequivocally, somebody had entered the site," says Di Martino. A few months later, samples of the Gebel Kamil meteorite - its official name - began to turn up at a market in France and online. The team was dismayed: the fragments disappearing into private hands meant vital information, such as the size of the meteorite that carved the crater, would be lost forever.

It is not the first time science has lost out to the burgeoning global trade in meteorites, which stretches from the bustling souks of Morocco to eBay. Meteorite researchers are racing private buyers to buy up these rare space rocks, and even helping dealers to identify fragments in exchange for samples. Yet participating in the trade helps to fuel it, and a small proportion of the meteorites for sale may have been snatched illegally from their country of origin. Should scientists collaborate with space rock vendors?

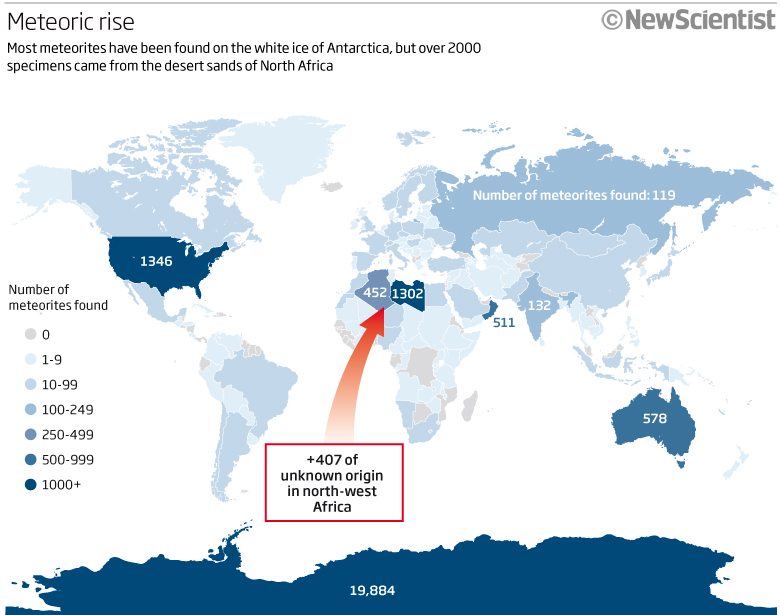

The global trade in meteorites has escalated in the last 20 years, largely because amateur hunters in North Africa have cottoned on to the fact that the rocks are there for the taking, because they are clearly visible on the bare desert surface (see map).

Markets in the French city of Ensisheim; in Tucson, Arizona, and Denver, Colorado, are among the most famous annual events attended by meteorite dealers and collectors. Among the minerals, old watches and shoddy jewellery on sale, it's possible to buy space rocks ranging from cheap meteorites up to true rarities such as lunar or Martian specimens. Prices vary from $1 per gram to $1000 or more for lunar or Martian rocks. Many are certified as genuine by an academic scientific body called the Meteoritical Society, and the trade's own body - the International Meteorite Collectors Association - has a code of ethics that demands its members do not trade fake rocks.

"The attraction of this year at Ensisheim were the Gebel Kamil meteorites," one dealer who attended the 2010 event told New Scientist. "There was a big crowd in front of the bench where the samples were being sold."

John T. Wasson of the University of California, Los Angeles, was just one of the researchers at Ensisheim this year buying up meteorites like Gebel Kamil. "I was not unique," he says. "You can say it would be better to avoid those places, I would say no if you want to know what kind of meteorites are coming into the market."

Wasson adds that some of the samples sold to researchers at Ensisheim "turned out to be very important pieces for science".

Dealers need to know a meteorite's type, and more importantly, its value, so it makes sense for them to bring a researcher on board. In return, the dealers donate, say, 20 grams of the sample to universities or academic collections. "I'm aware that researchers perform analyses for dealers. I don't like it, but I understand the logic," says Philip Bland, a meteorite researcher at Imperial College London. "If they don't do it then the meteorites will remain solely in private hands, sitting in a collection. The meteorites would be never seen again."

The trouble is that buying a rock or working with a dealer to value a find helps fuel a market that's harmful to science, as Pierre Rochette of the European Centre of Geosciences and Environment Research and Education (CEREGE), Aix en Provence, France, points out. Analysing a meteorite "adds value to what dealers will sell to private collectors and so, in a way, they contribute to the problem", he says.

What's more, if the provenance of a meteorite is unknown, it could have been traded illegally. Illicit or unethical trade of meteorites is considered to be particularly prevalent in north-west Africa, the source of many meteorites for sale. London's Natural History Museum now refuses to buy any meteorites from the region.

In Egypt, permission is supposed to be required to export meteorites. Di Martino and colleagues were authorised to take just 20 kilograms of Gebel Kamil out of the country. "Everything which is found in the Egyptian soil is property of the government," explains Tarek Hussein, who as former president of Egypt's Academy of Scientific Research and Technology was responsible for handling export applications until last April. He is concerned that many Gebel Kamil fragments that have appeared on the market in the west were not approved for export.

Similar rules are meant to apply in Morocco, Algeria and Libya, but local law-enforcement officers tend to make little effort to monitor trade. "Precious reservoirs of geological and archaeological material are flooding out of their own territories," says Rochette. These specimens belong in museums and labs in these countries, he adds.

Still, Bland believes that the majority of the meteorites acquired from dealers for research will have an untainted chain of ownership. And it would do more harm than good if scientists were to refuse a dealer's request to perform an analysis on a rock of unknown provenance. "Making a principled stand wouldn't affect the trade, wouldn't lead to a change in international law," he says. "In a sense those researchers are stuck, trying to make the best of a bad situation." However, they should be collectively lobbying for tighter laws, he adds.

Illicit export

The only international body in a position to monitor and regulate trade is UNESCO. Its Cultural Property Convention devised in 1970 is intended to prevent illicit import and export of everything from rare specimens of fauna and flora to geological treasures such as minerals and fossils. According to UNESCO's Edouard Planche, most of the 101 countries - including Morocco, Algeria and Libya - that ratified the convention subsequently passed laws to prevent untrammelled export of such "cultural goods".

Why aren't these laws enforced? "The problem is that before they are classified by a scientific authority or a team of experts, meteorites are just rocks," says Rochette. "There's no expert in airports that can distinguish a rock from a meteorite." At around $1 million a year, the trade in meteorites is small beer compared with illicit trade in say, wildlife, so governments may have less interest in policing the trade.

Canada is one of the few countries with a specific law to protect scientifically valuable meteorites: its Custom and Revenue Agency will only grant export permits for meteorites if it can be established that the fragment is not important to science.

Can scientific organisations have any input? The body that has perhaps the greatest power to make a difference is the Meteoritical Society, which certifies rocks as genuine. Dealers have an incentive to get this body's official recognition for a specimen, because it increases a rock's value. Yet the society has no specific policy aimed at keeping valuable meteorites in scientific hands, or at defining guidelines for its members, who are mainly researchers.

Jeff Grossmann, secretary of the Meteoritical Society, says that the issues raised by researchers dealing with possible illegal specimens have been informally discussed at various meetings in the past, but argues the society has limited powers. "We are a scientific institution," he says. "We cannot act as policemen. Researchers are in charge of checking on the origin of what they accept to analyse."

Not every member of the Meteoritical Society agrees. Several who wish to remain anonymous told New Scientist their suggestions for action from the society have been ignored. They propose delaying classification if a meteorite submitted to the society is suspected of being in violation of the UNESCO convention or national export rules. This would allow the national authority responsible for the preservation of natural heritage to be informed. If appropriate, a dealer could be given the option of donating a fragment for study or display in a national museum in exchange for the society's classification.

Another solution, says Bland, would be for western academic funding bodies to bypass dealers by financially compensating finders in places like North Africa. "Governments already pay to support extensive meteorite search programs in Antarctica," he says. "[We could] extend that to these other countries, introducing a scheme for compensating private individuals. The overall cost would probably be much less than the Antarctic research effort."

As for Di Martino and his colleagues, they are now arguing that the Kamil crater should be listed as a protected site by UNESCO, which would put pressure on the Egyptian government to step in to preserve it. Otherwise, the fragments will all disappear, just like the bottle left on the sand.

A lunar crater here on Earth

Kamil crater is more like a lunar crater than one typically found on Earth. It has a pristine "rayed" structure like wheel spokes, usually observed in the absence of an atmosphere. The dryness of the Egyptian desert has kept the crater intact for around 5000 years.

"It is like an open-air lab," says Luigi Folco, a geologist at the University of Siena, Italy, who helped analyse the first Kamil meteorites with Massimo D'Orazio of the University of Pisa, Italy.

The visible ejecta rays offer a rare opportunity to study the direction the meteorite came from and its impact speed. The Egyptian-Italian team estimate that the rock - an iron meteorite - weighed between 5000 and 10,000 kilograms and was about the size of a fridge, although they can't be sure because many of the fragments have now disappeared into private hands.

Iron meteorites of this size are usually thought to blast apart when they hit Earth's atmosphere, says Folco. But the team reckon only one big chunk broke off the meteorite before it landed (Science, DOI: link).

The crater was found thanks to Google Earth: Vincenzo De Michele, a retired geologist, spotted the crater while searching near the Sudanese-Egyptian border for ruins of Palaeolithic villages.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter