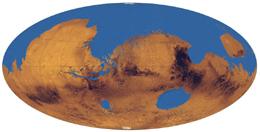

Hints that an ocean once occupied the northern lowlands of ancient Mars first arose in the late 1980s. Scientists examining pictures of the surface claimed to recognize extensive shorelines and vast networks of river valleys and outflow channels feeding in the same direction. Other researchers used thermal physics to imply that such networks could only have been carved by a complete water cycle, fuelled by one or more huge bodies of water.

Not all evidence has supported the idea of a Martian ocean, however. In the late 1990s, researchers studying high-resolution images of the proposed shoreline regions could not find any of the erosion and sediment normally associated with an ocean's edge. Nor have they since found the telltale coastal landforms seen on Earth, such as spits and wave-deposited ridges.

Gaetano Di Achille and Brian Hynek of the University of Colorado in Boulder, whose study could now tip the balance back in favour of an ancient ocean, initially had no interest in the debate. They had been building a database of Martian river deltas and valleys to examine how they might have been eroded by water, but ultimately realized that they had enough data to tackle the bigger picture. "Our research started as kind of a joke," says Di Achille. "We were working on this database of deltas and valleys, and we said: why don't we try to check this ocean hypothesis?"

Elevation issue

Di Achille and Hynek analysed the distribution and elevation of 52 deltas and numerous valley networks along Mars's northern lowlands. Of the deltas, 17 were at a very similar elevation and could not be dismissed as being the mouths of smaller tributaries or feeding isolated basins. A further 12 deltas fitted within the error bars of this average surface elevation, totalling 29 deltas, or 55% of those analysed, that seemed to feed the same body of water. The locations of the end points of the valleys also seemed to be consistent with a possible coastline. The research is published online in Nature Geoscience today.1

Taylor Perron, a geologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, says that the result "strengthens the argument in favour of oceans" but leaves some issues unresolved. He says that there is enough variability in the delta elevations to suggest that there is not just one level coastline, and that it is "hard to explain" why some valleys end at much higher elevations than the proposed ocean. "One possible explanation is a large-scale deformation of the planet, which warped the landscape, transforming what was once a level shoreline into one with more variable elevations," he says.

Di Achille thinks that this explanation doesn't work, because any widespread deformation should see the deltas' elevations sweep up and down in broad waves along the coastline, rather than narrowly scattered about it as they observed. In any case, he says, the variability in delta elevation on Mars is smaller than that found on Earth, and valleys almost always peter out on dry, higher land, so the question is moot.

Still, there is broad agreement from all sides that Di Achille and Hynek's analysis is not the last word on the existence of an ancient Martian ocean. If it did exist, at some point a dramatic change in climate probably caused it to disappear into the crust, into ice caps and out through the atmosphere. Now, 3.5 billion years later, researchers have the difficult task of finding evidence amid a landscape that has since been blighted by volcanism and cratering.

Caleb Fassett, a geoscientist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, says that the work will "stimulate new thinking" about past conditions on Mars. But he agrees that, as an indirect study, it needs backup from a more definitive method. "Finding further evidence for an ancient ocean besides the topography of Mars would have major implications," he says.

References

1. Di Achille, G. & Hynak, B. M. Nature Geoscience doi: 10.1038/NGEO891 (2010).

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter