Even if the "Underwear Bomber" Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab had exploded his device on Christmas day, 2009, the Airbus A330 would have survived, according to an experiment conducted by a BBC documentary team.

And while the person sitting next to Abdulmutallab probably would have died, the worst injury most passengers would have suffered would have been ruptured eardrums.

"What we tried to do was simulate, as far as we could, what might have happened over Detroit," said explosives expert John Wyatt, who was part of the BBC experiment. "We used the same type of explosive and the same amount and put it in the same position as the bomber."

"The supports adjacent to the seat lost five or six rivets and the metal bowed out, but the structure didn't fail," said Captain J. Joseph, an aviation expert also featured in the BBC documentary, which is also airing on Discovery Channel this week. "The actual aircraft would have remained intact."

On Dec. 25, 2009 Abdulmutallab boarded Northwest Airlines Flight 253, flying from Amsterdam to Detroit. Sewn into Abdulmutallab's underwear was pentaerythirtol tetranitrate, or PETN, a powerful explosive.

As the Airbus A330 was about to touch down in Detroit, Abdulmutallab allegedly removed a syringe and tried to ignite the PETN and blow up the aircraft. Instead of a powerful explosion, however, Abdulmutallab created a small fire, which was extinguished. The would-be bomber was subdued by other passengers and crew members on the flight.

Using a decommissioned Boeing 747, Joseph, Wyatt and the BBC team set about recreating the conditions of last year's attempted bombing.

They placed about 80 grams of PETN's base material, pentaerythritol, near the 747's fuselage where Abdulmutallab was seated. Eighty grams of pentaerythritol contains about the same explosive power as a hand grenade, but lacks the the hot, sharp metal fragments of an actual grenade that cause so much damage. The BBC set up cameras and Wyatt set off the explosives.

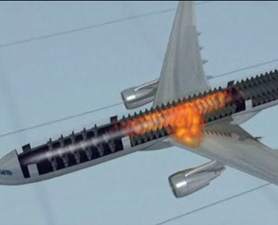

In the BBC documentary, entitled How Safe Are Our Skies, the controlled detonation of the explosives lasted a scant 0.94 milliseconds, but the results were clear to cameras. Shock waves rippled through the exterior aluminum skin of the aircraft like fat water drops of water hitting the surface of a smooth pond.

The metal was permanently bowed out, and a handful of rivets were punched out, but no gaping holes appeared. The pressurized air inside the cabin would have slowly leaked out of the missing rivets, said Joseph, a non- life-threatening situation. The amount of explosives was "nowhere near enough" to bring down the plane, concluded Wyatt and Joseph.

The aircraft would have survived, but some of the passengers would not have. The alleged would-be bomber and the person seated next to him would both have likely died, said Wyatt.

The passengers sitting in front of and behind the terrorist would probably have been protected from serious bodily injury the the aircraft's metal seats. Most passengers on the plane would have suffered ruptured eardrums as the shock wave created by the bomb traveled through the plane's cabin.

The BBC also used a decommissioned Boeing 747 and not a newer Airbus A330 for the test. An actual test would be necessary to prove this, but Wyatt and Joseph think that the newer plane, which was made with lighter and stronger composite materials instead of aluminum, would have performed even better.

The newest commercial passenger jet, the Boeing 747 or Dreamliner, which has even more composite materials, would likely perform even better, said Wyatt, although he doesn't know for sure.

The BBC test plane was at rest under normal atmospheric pressure, not pressurized. The difference in pressure was irrelevant, said Wyatt.

"It's over so quickly that the difference in pressure wouldn't make a difference," said Wyatt. "By the time the shock wave got to the door the pressure would have normalized."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter