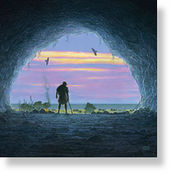

© Kazuhiko Sano

Paleoanthropologists know more about Neandertals than any other extinct human. But their demise remains a mystery, one that gets curiouser and curiouser.

Neandertals, our closest relatives, ruled Europe and western Asia for more than 200,000 years. But sometime after 28,000 years ago, they vanished. Scientists have long debated what led to their disappearance. The latest extinction theories focus on climate change and subtle differences in behavior and biology that might have given modern humans an advantage over the Neandertals.

Some 28,000 years ago in what is now the British territory of Gibraltar, a group of Neandertals eked out a living along the rocky Mediterranean coast. They were quite possibly the last of their kind. Elsewhere in Europe and western Asia, Neandertals had disappeared thousands of years earlier, after having ruled for more than 200,000 years. The Iberian Peninsula, with its comparatively mild climate and rich array of animals and plants, seems to have been the final stronghold. Soon, however, the Gibraltar population, too, would die out, leaving behind only a smattering of their stone tools and the charred remnants of their campfires.

Ever since the discovery of the first Neandertal fossil in 1856, scientists have debated the place of these bygone humans on the family tree and what became of them. For decades two competing theories have dominated the discourse. One holds that Neandertals were an archaic variant of our own species, Homo sapiens, that evolved into or was assimilated by the anatomically modern European population. The other posits that the Neandertals were a separate species, H. neanderthalensis, that modern humans swiftly extirpated on entering the archaic hominid's territory.

Over the past decade, however, two key findings have shifted the fulcrum of the debate away from the question of whether Neandertals and moderns made love or war. One is that analyses of Neandertal DNA have yet to yield the signs of interbreeding with modern humans that many researchers expected to see if the two groups mingled significantly. The other is that improvements in dating methods show that rather than disappearing immediately after the moderns invaded Europe, starting a little more than 40,000 years ago, the Neandertals survived for nearly 15,000 years after moderns moved in - hardly the rapid replacement adherents to the blitzkrieg theory envisioned.

These revelations have prompted a number of researchers to look more carefully at other factors that might have led to Neandertal extinction. What they are finding suggests that the answer involves a complicated interplay of stresses.

A World in FluxOne of the most informative new lines of evidence bearing on why the Neandertals died out is paleoclimate data. Scholars have known for some time that Neandertals experienced both glacial conditions and milder interglacial conditions during their long reign. In recent years, however, analyses of isotopes trapped in primeval ice, ocean sediments and pollen retrieved from such locales as Greenland, Venezuela and Italy have enabled investigators to reconstruct a far finer-grained picture of the climate shifts that occurred during a period known as oxygen isotope stage 3 (OIS-3). Spanning the time between roughly 65,000 and 25,000 years ago, OIS-3 began with moderate conditions and culminated with the ice sheets blanketing northern Europe.

Considering that Neandertals were the only hominids in Europe at the beginning of OIS-3 and moderns were the only ones there by the end of it, experts have wondered whether the plummeting temperatures might have caused the Neandertals to perish, perhaps because they could not find enough food or keep sufficiently warm. Yet arguing for that scenario has proved tricky for one essential reason: Neandertals had faced glacial conditions before and persevered.

In fact, numerous aspects of Neandertal biology and behavior indicate that they were well suited to the cold. Their barrel chests and stocky limbs would have conserved body heat, although they would have additionally needed clothing fashioned from animal pelts to stave off the chill. And their brawny build seems to have been adapted to their ambush-style hunting of large, relatively solitary mammals - such as woolly rhinoceroses - that roamed northern and central Europe during the cold snaps. (Other distinctive Neandertal features, such as the form of the prominent brow, may have been adaptively neutral traits that became established through genetic drift, rather than selection.)

But the isotope data reveal that far from progressing steadily from mild to frigid, the climate became increasingly unstable heading into the last glacial maximum, swinging severely and abruptly. With that flux came profound ecological change: forests gave way to treeless grassland; reindeer replaced certain kinds of rhinoceroses. So rapid were these oscillations that over the course of an individual's lifetime, all the plants and animals that a person had grown up with could vanish and be replaced with unfamiliar flora and fauna. And then, just as quickly, the environment could change back again.

It is this seesawing of environmental conditions - not necessarily the cold, per se - that gradually pushed Neandertal populations to the point of no return, according to scenarios posited by such experts as evolutionary ecologist Clive Finlayson of the Gibraltar Museum, who directs the excavations at several cave sites in Gibraltar. These shifts would have demanded that Neandertals adopt a new way of life in very short order. For example, the replacement of wooded areas with open grassland would have left ambush hunters without any trees to hide behind, he says. To survive, the Neandertals would have had to alter the way they hunted.

Some Neandertals did adapt to their changing world, as evidenced by shifts in their tool types and prey. But many probably died out during these fluctuations, leaving behind ever more fragmented populations. Under normal circumstances, these archaic humans might have been able to bounce back, as they had previously, when the fluctuations were fewer and farther between. This time, however, the rapidity of the environmental change left insufficient time for recovery. Eventually, Finlayson argues, the repeated climatic insults left the Neandertal populations so diminished that they could no longer sustain themselves.

The results of a genetic study published this past April in PLoS One by Virginie Fabre and her colleagues at the University of the Mediterranean in Marseille support the notion that Neandertal populations were fragmented, Finlayson says. That analysis of Neandertal mitochondrial DNA found that the Neandertals could be divided into three subgroups - one in western Europe, another in southern Europe and a third in western Asia - and that population size ebbed and flowed.

Invasive SpeciesFor other researchers, however, the fact that the Neandertals entirely disappeared only after moderns entered Europe clearly indicates that the invaders had a hand in the extinction, even if the newcomers did not kill the earlier settlers outright. Probably, say those who hold this view, the Neandertals ended up competing with the incoming moderns for food and gradually lost ground. Exactly what ultimately gave moderns their winning edge remains a matter of considerable disagreement, though.

One possibility is that modern humans were less picky about what they ate. Analyses of Neandertal bone chemistry conducted by Hervé Bocherens of the University of Tübingen in Germany suggest that at least some of these hominids specialized in large mammals, such as woolly rhinoceroses, which were relatively rare. Early modern humans, on the other hand, ate all manner of animals and plants. Thus, when moderns moved into Neandertal territory and started taking some of these large animals for themselves, so the argument goes, the Neandertals would have been in trouble. Moderns, meanwhile, could supplement the big kills with smaller animals and plant foods.

"Neandertals had a Neandertal way of doing things, and it was great as long as they weren't competing with moderns," observes archaeologist Curtis W. Marean of Arizona State University. In contrast, Marean says, the moderns, who evolved under tropical conditions in Africa, were able to enter entirely different environments and very quickly come up with creative ways to deal with the novel circumstances they encountered. "The key difference is that Neandertals were just not as advanced cognitively as modern humans," he asserts.

Marean is not alone in thinking that Neandertals were one-trick ponies. A long-standing view holds that moderns outsmarted the Neandertals with not only their superior tool technology and survival tactics but also their gift of gab, which might have helped them form stronger social networks. The Neandertal dullards, in this view, did not stand a chance against the newcomers.

But a growing body of evidence indicates that Neandertals were savvier than they have been given credit for. In fact, they apparently engaged in many of the behaviors once believed to be strictly the purview of modern humans. As paleoanthropologist Christopher B. Stringer of London's Natural History Museum puts it, "the boundary between Neandertals and moderns has gotten fuzzier."

Sites in Gibraltar have yielded some of the most recent findings blurring the line between the two human groups. In September 2008 Stringer and his colleagues reported on evidence that Neandertals at Gorham's Cave and next-door Vanguard Cave hunted dolphins and seals as well as gathered shellfish. And as yet unpublished work shows that they were eating birds and rabbits, too. The discoveries in Gilbraltar, along with finds from a handful of other sites, upend the received wisdom that moderns alone exploited marine resources and small game.

More evidence blurring the line between Neandertal and modern human behavior has come from the site of Hohle Fels in southwestern Germany. There paleoanthropologist Bruce Hardy of Kenyon College was able to compare artifacts made by Neandertals who inhabited the cave between 36,000 and 40,000 years ago with artifacts from modern humans who resided there between 33,000 and 36,000 years ago under similar climate and environmental conditions. In a presentation given this past April to the Paleoanthropology Society in Chicago, Hardy reported that his analysis of the wear patterns on the tools and the residues from substances with which the tools came into contact revealed that although the modern humans created a larger variety of tools than did the Neandertals, the groups engaged in mostly the same activities at Hohle Fels.

These activities include such sophisticated practices as using tree resin to bind stone points to wooden handles, employing stone points as thrusting or projectile weapons, and crafting implements from bone and wood. As to why the Hohle Fels Neandertals made fewer types of tools than did the moderns who lived there afterward, Hardy surmises that they were able to get the job done without them. "You don't need a grapefruit spoon to eat a grapefruit," he says.

The claim that Neandertals lacked language, too, seems unlikely in light of recent discoveries. Researchers now know that at least some of them decorated their bodies with jewelry and probably pigment. Such physical manifestations of symbolic behavior are often used as a proxy for language when reconstructing behavior from the archaeological record. And in 2007 researchers led by Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, reported that analyses of Neandertal DNA have shown that these hominids had the same version of the speech-enabling gene FOXP2 that modern humans carry.

TiebreakersWith the gap between Neandertal and modern human behavior narrowing, many researchers are now looking to subtle differences in culture and biology to explain why the Neandertals lost out. "Worsening and highly unstable climatic conditions would have made competition among human groups all the more fierce," reflects paleoanthropologist Katerina Harvati, also at Max Planck. "In this context, even small advantages would become extremely important and might spell the difference between survival and death."

Stringer, for his part, theorizes that the moderns' somewhat wider range of cultural adaptations provided a slightly superior buffer against hard times. For example, needles left behind by modern humans hint that they had tailored clothing and tents, all the better for keeping the cold at bay. Neandertals, meanwhile, left behind no such signs of sewing and are believed by some to have had more crudely assembled apparel and shelters as a result.

Neandertals and moderns may have also differed in the way they divvied up the chores among group members. In a paper published in Current Anthropology in 2006, archaeologists Steven L. Kuhn and Mary C. Stiner, both at the University of Arizona, hypothesized that the varied diet of early modern Europeans would have favored a division of labor in which men hunted the larger game and women collected and prepared nuts, seeds and berries. In contrast, the Neandertal focus on large game probably meant that their women and children joined in the hunt, possibly helping to drive animals toward the waiting men. By creating both a more reliable food supply and a safer environment for rearing children, division of labor could have enabled modern human populations to expand at the expense of the Neandertals.

However the Neandertals obtained their food, they needed lots of it. "Neandertals were the SUVs of the hominid world," says paleoanthropologist Leslie Aiello of the Wenner-Gren Foundation in New York City. A number of studies aimed at estimating Neandertal metabolic rates have concluded that these archaic hominids required significantly more calories to survive than the rival moderns did.

Hominid energetics expert Karen Steudel-Numbers of the University of Wisconsin - Madison has determined, for example, that the energetic cost of locomotion was 32 percent higher in Neandertals than in anatomically modern humans, thanks to the archaic hominids' burly build and short shinbones, which would have shortened their stride. In terms of daily energy needs, the Neandertals would have required somewhere between 100 and 350 calories more than moderns living in the same climates, according to a model developed by Andrew W. Froehle of the University of California, San Diego, and Steven E. Churchill of Duke University. Modern humans, then, might have outcompeted Neandertals simply by virtue of being more fuel-efficient: using less energy for baseline functions meant that moderns could devote more energy to reproducing and ensuring the survival of their young.

One more distinction between Neandertals and moderns deserves mention, one that could have enhanced modern survival in important ways. Research led by Rachel Caspari of Central Michigan University has shown that around 30,000 years ago, the number of modern humans who lived to be old enough to be grandparents began to skyrocket. Exactly what spurred this increase in longevity is uncertain, but the change had two key consequences. First, people had more reproductive years, thus increasing their fertility potential. Second, they had more time over which to acquire specialized knowledge and pass it on to the next generation - where to find drinking water in times of drought, for instance. "Long-term survivorship gives the potential for bigger social networks and greater knowledge stores," Stringer comments. Among the shorter-lived Neandertals, in contrast, knowledge was more likely to disappear, he surmises.

More clues to why the Neandertals faded away may come from analysis of the Neandertal genome, the full sequence of which is due out this year. But answers are likely to be slow to surface, because scientists know so little about the functional significance of most regions of the modern genome, never mind the Neandertal one. "We're a long way from being able to read what the [Neandertal] genome is telling us," Stringer says. Still, future analyses could conceivably pinpoint cognitive or metabolic differences between the two groups, for example, and provide a more definitive answer to the question of whether Neandertals and moderns interbred.

The Stone Age whodunit is far from solved. But researchers are converging on one conclusion: regardless of whether climate or competition with moderns, or some combination thereof, was the prime mover in the decline of the Neandertals, the precise factors governing the extinction of individual populations of these archaic hominids almost certainly varied from group to group. Some may have perished from disease, others from inbreeding. "Each valley may tell its own story," Finlayson remarks.

As for the last known Neandertals, the ones who lived in Gibraltar's seaside caves some 28,000 years ago, Finlayson is certain that they did not spend their days competing with moderns, because moderns seem not to have settled there until thousands of years after the Neandertals were gone. The rest of their story, however, remains to be discovered.

Note: This article was originally printed with the title, "Twilight of the Neandertals."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter