You also know, of course, that psychiatric patients routinely make such claims, and that some, if they are granted temporary leave, will try to take their lives. But this particular patient swears they are telling the truth. They look, and sound, sincere. So here's the question: is there any way you can be sure they are telling the truth?

It set Ekman thinking. As part of his research, he had already recorded a series of 12-minute interviews with patients at the hospital. In a subsequent conversation, one of the patients told him that she had lied to him. So Ekman sat and looked at the film. Nothing. He slowed it down, and looked again. Slowed it further.

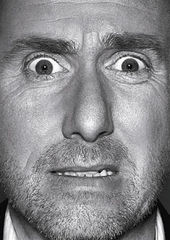

And suddenly, there, across just two frames, he saw it: a vivid, intense expression of extreme anguish. It lasted less than a 15th of a second. But once he had spotted the first expression, he soon found three more examples in that same interview. "And that," says Ekman, "was the discovery of microexpressions: very fast, intense expressions of concealed emotion."

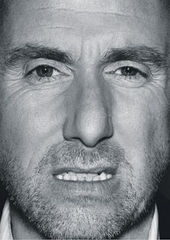

Over the course of the next four decades, at the University of California's department of psychiatry in San Francisco, Ekman has successfully demonstrated a proposition first suggested by Charles Darwin: that the ways in which we express anger, disgust, contempt, fear, surprise, happiness and sadness are both innate and universal.

But particularly when we are lying, "microexpressions" of powerfully-felt emotions will invariably flit across our faces before we get a chance to stop them.

Fortunately for liars, as many as 99% of people will fail to spot these fleeting signals of inner torment (of the 15,000 whom Ekman has tested, only 50 people have been able to without training. He calls them "naturals").

But given a bit of training, Ekman says, almost anyone can develop the skill. He should know: since the mid-80s and the first publication of his best-known book, Telling Lies, he has been called in by the FBI, CIA, the US Transportation Security Administration, immigration authorities, anti-terrorist investigators and police forces around the world not just to help crack cases, but to teach them how to use the technique themselves. He has held workshops for defence and prosecution lawyers, health professionals, poker players, even jealous spouses, and created an online course - so with the aid of a $20 CD-Rom or a $12 internet lesson, you too could soon be able to tell exactly when someone is telling porkies.

Sound like a good scenario for a TV drama? Of course it does. Lie to Me, a new series from Rupert Murdoch's US Fox network which premieres this week on Sky1, stars British actor Tim Roth as (I quote) "Dr Cal Lightman, the world's leading deception expert, a scientist who studies facial expressions and involuntary body language to discover not only if you are lying but why". More accurate than any polygraph test, Sky's publicity blurb says Lightman is "a human lie detector".

He was won over by the manifestly serious intent of Grazer and Samuel Baum, the show's writer, and decided the role they held out to him as scientific advisor should be a hands-on one. As a result the series is, he reckons, "probably 80-90% accurate; in the pilot episode, of the 18 things they use, only two are not correct. But you have to remember this is a drama, not a documentary. Lightman solves cases more quickly and more certainly than in the real world."

To ensure his scientific reputation remains unblemished, Ekman has written a blog on the show's website after each episode broadcast so far in the US. Called The Truth About Lie to Me, it provides a detailed postmortem of each programme, probing the nuances and highlighting what was fact, and what had been embroidered for the purposes of dramatic effect.

And he is keen to point out that while the show may be based on his work, Lightman is most certainly not Ekman. "He's British, for a start. Also he's younger, and more arrogant. And he does things I would never do. He lies to people himself, for example, to elicit the truth. I entirely disapprove of that, although the US supreme court has ruled it's admissible."

Ekman, incidentally, professes to be "a terrible liar", and observes that although some people are plainly more accomplished liars than others, he cannot teach anyone how to lie. "The ability to detect a lie and the ability to lie successfully are completely unrelated," he says. "I have been asked by people running for high office - for very high office - if I could teach them to become 'more credible'. But I don't work that side of the street."

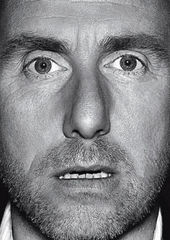

The psychologist's techniques, he concedes, can only be a starting point for the crime investigators or security officials applying them. "All they show is that someone's lying," he says. "You have to proceed very cautiously when you recognise concealed emotion. You have to question very carefully, because what you really want to know is why they are lying. No expression of emotion, micro or macro, reveals exactly what is triggering it."

Suppose, Ekman posits, "my wife has been found murdered in our hotel. I would be the prime suspect, because most wives are murdered by their husbands. How would I react when the police questioned me? My demeanour might well be consistent with a concealed emotion. That could be because I was guilty. But it could equally be because I was extremely angry at being a suspect, yet frightened of showing anger because I knew it might make the police think I was guilty. A microexpression is just a tiny little breach; you have to widen it, deepen it, explore further."

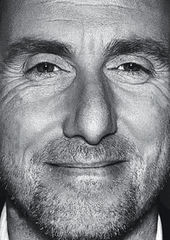

Plus, there are lies and lies. Ekman defines a lie as having two essential characteristics: there must be a deliberate choice and intent to mislead, and there must be no notification that this is what is occurring. "An actor or a poker player isn't a liar," he says. "They're supposed to be deceiving you, it's part of the game. Likewise flattery. I focus on serious lies: where the consequences for the liar are grave if they're found out, and where the target would feel properly aggrieved if they knew." (Although, distractingly, even some serious lies can be good. When Ekman was waiting for a biopsy report on a suspected cancer some years ago, he says by way of example, "I lied to my wife when she asked me why I was acting strangely. That was a 'good' lie. You have to put yourself in the position of the persons involved.")

Generally, though, the lies that interest Ekman - and Dr Cal Lightman - are those in which "the threat of loss or punishment to the liar is severe: loss of job, loss of reputation, loss of spouse, loss of freedom". Fortunately, those are also the lies that are detectable, because those are the kind of lies that invariably produce clues in the liar's demeanour.

But how reliable are Ekman's methods? Microexpressions, he says, are only part of a whole set of possible deception indicators. "There are also what we call subtle expressions - not brief, but very small, almost imperceptible. A very slight tightening of the lips, for example, is the most reliable sign of anger. You need to study a person's whole demeanour: gesture, voice, posture, gaze, and also, of course, the words themselves."

Just read microexpressions and subtle expressions correctly, however, and Ekman reckons your accuracy in detecting an attempt at deception "will increase from chance to 70% or better". In comparison, when it comes to spotting really serious lies - those that could, for example, affect national security - he says simply that he "does not believe we have solid evidence that anything else works better than chance". Is he lying? I couldn't tell. But it makes for pretty engrossing telly.

you can tell if they're lying if their lips are moving.

Too bad they didn't include psychopathy in this article. I wonder if Ekman is aware psychopaths don't feel the same emotions normal humans do, and so would react differently to telling lies?