Scientists found the vast and sticky empire stretching 40 feet across, consisting of billions of genetically identical single-celled individuals, oozing along in the muck of a cow pasture outside Houston.

"It was very unexpected," said Owen M. Gilbert, a graduate student at Rice University and lead author of the report in the March issue of Molecular Ecology. "It was like nothing we'd ever seen before."

Scientists say the discovery is much more than a mere curiosity, because the colony consists of what are known as social amoebas. Only an apparent oxymoron, social amoebas are able to gather in organized groups and behave cooperatively, some even committing suicide to help fellow amoebas reproduce. The discovery of such a huge colony of genetically identical amoebas provides insight into how such cooperation and sociality might have evolved and may help to explain why microbes are being found to show social behaviors more often than was expected.

"It is of significant scientific interest," said Kevin Foster, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University who was not involved with the study. Though amoebas would seem unlikely to coordinate interactions with one another over much more than microscopic distances, the discovery of such a massive clonal colony, he said, "raises the possibility that cells might evolve to organize on much larger spatial scales."

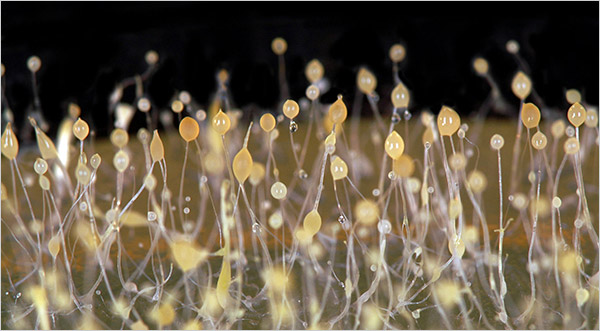

Thoughts of a giant organized amoeba colony can conjure up visions of the 1958 horror classic The Blob, but these social amoebas, a species known as Dictyostelium discoideum, a kind of slime mold, are infinitely more subtle. Microscopic and tucked away in the dirt, the billions of amoebas would have gone unnoticed by anyone driving past the pasture. Joan Strassmann, an author on the paper along with another evolutionary biologist at Rice University, David Queller, said she and a team of undergraduates searched for the species by sticking drinking straws into dirt and cow dung to retrieve materials where the amoebas might be living. In the laboratory, they spread the samples on Petri dishes and waited to see what would grow. DNA analyses later showed that the huge numbers of amoebas collected from the pasture were genetically identical.

Bernard Crespi, an evolutionary biologist at Simon Fraser University in Canada, said the study was the first to clearly demonstrate "the extreme of relatedness" in social microbes, a population of genetically identical individuals. Such a colony provides the ideal conditions to foster the evolution of behaviors like cooperation, because the more genetically similar two organisms are, the more natural selection will favor their assisting each other.

Dictyostelium, for example, can carry out stunning feats of cooperation, engaging in what's known as suicidal altruism, a behavior in which individual amoebas come together to form a single body, with some amoebas sacrificing themselves to allow for more effective reproduction of amoebas in other parts of the body.

Scientists said that if other species were also found to have such clonal colonies, that could help explain the surprisingly widespread finding of social behaviors among microbes. But just what conditions prompt the flourishing of clones remains unclear. Scientists said it was odd to find the slime molds thriving in an open field, as they prefer enclosed forest soils. It is possible that the lumbering cows fostered the growth of the giant clone colony by spreading the amoebas through the muck, said John Bonner, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton University.

Meanwhile, as impressive (or even threatening) as a colony of a couple billion amoebas might sound, it has turned out to be surprisingly fragile.

"Just one week later, it had rained a lot and then it basically was gone," Mr. Gilbert said.

Apparently, such is the fleeting nature of grand amoebic phenomena, for the Texas clone is not the first to dwindle inexplicably into nothingness. Scientists say that the last traces of what at one point may have been the world's largest individual amoeba - and the star of a highly productive research program - shriveled in their laboratory last summer until it disappeared.

Manfred Schliwa, a cell biologist at the University of Munich, first came across the organism, known as Reticulomyxa, quite by accident as it spread as a white slime across the fish tank in his office at the University of California at Berkeley where he was then a professor.

The amoeba, a blob with no defined shape, bits of which could break off to take up a life of their own, fed so heartily off stray morsels of fish food that it eventually attained the status of giant among microbes, its body reaching more than an inch across.

A single enormous cell, the amoeba was studied by Dr. Schliwa and colleagues to understand movement from one part of a cell to another, a process that was both easily visualized and carried out extremely rapidly in the big Reticulomyxa, which at its largest could house a billion or more nuclei as it constantly shuttled cell parts and whatnot across its titanic form.

Dr. Schliwa, still mystified by the demise of the big-amoeba-that-couldn't, said he hoped at some point to obtain a new wild Reticulomyxa, though under natural conditions the organism is much smaller and lives in the soil, making it difficult to spot. In fact, like the colony of social amoebas, the giant amoebas could be everywhere underfoot without anyone's noticing.

"I used to joke," Dr. Schliwa said, "that there might be a giant organism in the soil spanning the entire continent and whenever you dig up a shovelful you get a piece of it."

So where will the next giant amoeba be found hiding? Dr. Schliwa points out that the original discovery of the amoeba-to-end-all-amoebas was made in the 1940s by a researcher named Ruth N. Nauss. She discovered the species in a New York City park.

So NO ONE ever stopped to think Gaia pourrait avoir ses propres systèmes?

I always thought that amoebas were the Earth's own cells, isn't there some biological indicator that measures amoebas as confusingly more complex than human cells?

Man, Mom must be LIVID about the satellite mess...