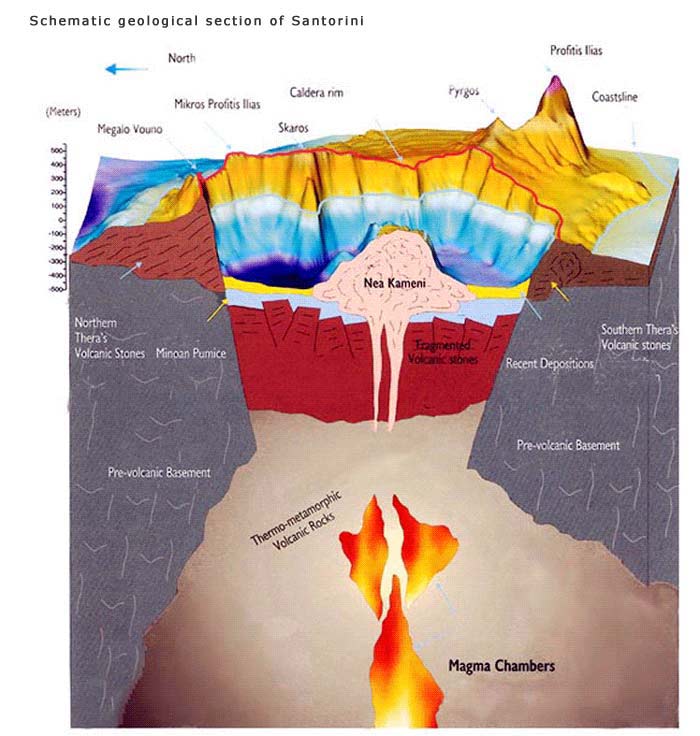

Schematic geological section of Santorini

Little wonder the ancients believed in lightning-bolt-throwing gods and smoking monsters emerging from the underworld. As a new marine geology survey of an ancient volcano in the Aegean Sea reveals, they may have been justifiably cowed.

Not much is left of the Santorini Islands, among Greece's prettiest tourist sites. They encircle a massive volcanic crater, where more than 3,500 years ago one of the largest eruptions in recorded history took place.

The blast entombed an ancient town, Akrotiri, and seemingly altered the course of world history.

And now the survey indicates that the eruption was even more powerful than once believed.

"The Minoan eruption of the Santorini volcano has remained of great interest to geologists, historians, and archeologists because of its possible impact on the Minoan civilization in Crete," notes the survey in the August 22

Eos journal. The Minoans were major players in the Eastern Mediterranean from roughly 3,000 B.C. to 1550 B.C, when the ancient Greeks, the same guys who went on to besiege Troy, took over. The late Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos in 1939 proposed that the eruption, a scant 70 miles away from Crete, caused the end of the Minoan civilization.

It was some blast, says vulcanologist Haraldur Sigurdsson of the University of Rhode Island, lead author of the

Eos study. The total volume of material belched from the eruption was a mile-square pile of dirt stacked nine miles high, making the blast about 120 times more powerful than the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, Sigurdsson says. The survey shows the Santorini Islands are surrounded by 530 square miles of volcanic rock on the ocean floor, in places close to the coast up to 260 feet thick.

The rock likely rode across the ocean waves at the time of the eruption, a superheated "pyroclastic" wave of light ash and pumice. In its extent, it exceeded the 1815 Tambora eruption that killed 36,000 in Indonesia, the study concludes, the previous record holder. Ash, pyroclastic flow and tsunami likely combined to similar, deadly effect in the Mediterranean, Sigurdsson says.

"This is extremely exciting news," says an expert on the Late Bronze Age Aegean, Eric Cline, who is currently chairman of the Classics department at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. "If the explosion were so much larger than previously thought, then we may have to look again at the potential impact that it had on Minoan Crete at the time, as well as upon Bronze Age civilizations as far away as Egypt, Turkey, and Mainland Greece."

The undersea survey also shows the nearby undersea volcano, Kolumbo, the largest of 20 volcanic cones around the islands, is still very much alive. An unexpected "widespread hydrothermal vent field was discovered on the floor of the Kolumbo submarine crater," the study says. Using robotic submersibles run by noted Titanic explorer, Robert Ballard, the team peeked 1,500 feet down into Kolumbo.

The floor of the crater is covered with bacterial mats, scattered among the vents, some of them belching 428-degree Fahrenheit steam. Sulfur-rich deposits of lead, iron and precious metals cover the vents.

The key issue for scholars in evaluating the volcano's effect is in resolving a dispute over the exact time of the eruption, Cline says. Some archaeologists, based on pottery and ancient Egyptian inscriptions, put the date at 1500 B.C. Experts in radiocarbon dating put it further back, to at least 1600 B.C. In April, a pair of new radiocarbon reports in

Science magazine, one based on leaves and twigs buried in the eruption, overlapped to pin the date to between 1613 to 1627 B.C. Egyptologists such as Manfred Bietak of Austria's University of Vienna told

Science they were unimpressed with the new dates however, so the debate continues.

Sigurdsson is convinced that the blast played a big role in the mythology of the ancient Greeks. "In my mind, personally, the mythology born out of this largest eruption must be responsible for the Atlantis legend," he says, referring to the lost continent of story and song. He also compares the event to the ancient poet Hesiod's work,

The Theogony, which tells of the world's origins.

"

The poem describes the battles between the gods and titans on Mount Olympus in language that nicely describes a volcanic eruption," Sigurdsson says. Stones are thrown, seas boil, smoke belches forth from the earth - all the stormy drama that mythology can muster. "Hesiod's ancestors lived to tell the tale after seeing something incredible happen in the sea and they interpreted a godly myth to explain what they had survived," he suggests.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter