"I was missing the capability to experience the sexual sensations to the fullness that nature has seemingly designed us for," Low recently told Undark in an email. In the early days of his research, he found material suggesting that circumcision affects penile sensitivity and sex. Then he discovered forums where circumcised men were discussing techniques for regrowing the foreskin.

Soon, Low was taking steps to reverse the surgery that had been performed on him as an infant — too young, he pointed out, to give informed consent.

Some men, meanwhile, have had a different journey. Lee Caddick was not circumcised as a child. He decided to get the procedure at age 48, after decades of suffering from a too-tight foreskin that made erections and sex both painful and embarrassing. Growing up in England, there had been few opportunities to talk earnestly about penises and sexual function. "I wish I had got it done earlier," he said. "It might have made a big difference in my life."

Male circumcision is one of the world's oldest surgeries and remains one of the most common procedures today. It involves the removal of all or part of the foreskin, known as the prepuce, and can be carried out at any age for religious, medical, or other reasons. Rates of the procedure vary widely by country: from 71 percent of males in the United States to 21 percent in the United Kingdom, from 92 percent in Israel to less than 1 percent in Ireland, according to a 2016 estimate.

Some religions practice infant circumcision, but in the U.S., religious reasons account for just a tiny percentage of all newborns who get circumcised. Most parents arrange for their child to have the procedure for medical reasons. The American Academy of Pediatrics, or AAP, currently states that families should be given access to the surgery, on the grounds that it may reduce the risk of acquiring certain infections. Complications are infrequent and generally minor, according to the AAP, particularly when the procedure is performed on newborns.

Yet the AAP did not issue a blanket recommendation, stating that the procedure's "health benefits are not great enough" to warrant one. In fact, claims that circumcision improves health are increasingly the subject of heated, and occasionally acrimonious, debate. When Andrew Freedman, a California-based pediatric urologist, agreed to contribute to the AAP's policy statement, a friend who had worked on the previous task force warned him against it. The topic was too fraught.

"He said, 'Don't do it. You'll get death threats.'"

The friend was not far off, Freedman said. After the policy statement was released, angry messages flooded his inbox: "Twenty thousand people sent me emails suggesting I get cancer and die," he recalled.

That anger stemmed in part from the fact that circumcision's medical benefits are not clear-cut. And for many men, being circumcised — or, for that matter, being uncircumcised — is not merely a question of medicine, but one of aesthetics, consent, bodily autonomy, and sexual pleasure.

"There's a lot of mythology around it," said Caddick, referring to circumcision's influence on sex. "You know, there are people who say their orgasms are more intense, which I think could be true. And there are other people who say you lose like 90 percent of your sensitivity." Scholarly research, it turns out, supports Caddick's impression that men's experiences with circumcision and sexual function vary widely.

"I think everybody's experience is different," he said.

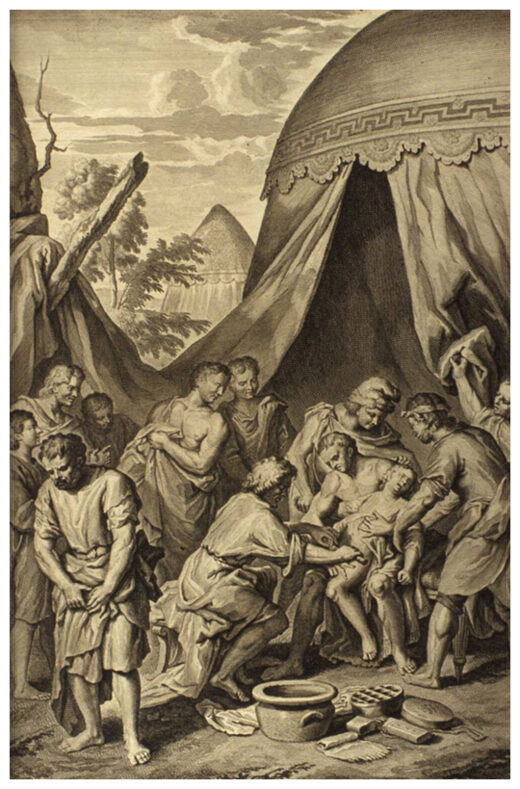

The procedure may date back to the Paleolithic Age, as cave paintings from that period show possibly circumcised penises. Circumcision emerged as a medical intervention within Western medicine in 1870. An American surgeon named Lewis Sayre had been asked to evaluate a 5-year-old boy whose legs were partially paralyzed. During the evaluation, Sayre determined that the boy's penis was "imprisoned" within the foreskin. He decided to circumcise the patient under anesthesia.

Within days, the child's health improved: Color returned to his cheeks, and he "was able to walk with his limbs quite straight," according to the historian David Gollaher, whose book traces the history of circumcision. Sayre hypothesized that the procedure had somehow quieted the boy's nervous system, thus returning the child to good health.

There was, of course, no real evidence for such a connection between circumcision and the boy's recovery from paralysis, but it didn't matter. From there, physicians began to hypothesize that circumcision could cure a wide range of maladies, Gollaher writes, including madness, epilepsy, and the temptation to masturbate.

Circumcision also came to signify high social status because doctors, not midwives, could perform the surgeries. The historian Ronald Hyam observed that the procedure was considered particularly useful for British newborns, who might one day find themselves living in a far-away colony where their supposedly sensitive foreskins might not adapt well to the hot and humid climate.

Rates began to decline later in the 20th century as some countries created publicly-funded health care systems. These systems typically required medical interventions to undergo a formal cost-benefit analysis, and circumcision rarely cleared the bar. When the U.K.'s National Health Service was created in 1948, for example, administrators decided not to cover the procedure because physicians disagreed about its medical value.

Over time, countries also started to weigh potential harms. In 2010, the Royal Dutch Medical Association, which represents doctors in the Netherlands, described circumcision as in conflict with a child's right to physical integrity. In Germany, an intense debate arose in 2012, when a Muslim boy was injured following a routine circumcision. Today, the procedure is legal, but German medical organizations have pushed for bans unless there is a medical indication.

The foreskin is densely packed with nerves that generate sexual arousal, said Christoph Kupferschmid, a pediatrician and chair of the Committee for Ethical Issues in the German Alliance for Child and Adolescent Health. For this reason, many European physicians recommend circumcision only when medically necessary.

The U.S. has followed a different track, perhaps because its commercialized health care system left the decision up to parents and clinicians. The American Academy of Pediatrics does provide recommendations, but for about 50 years, its guidance has zigzagged.

In 1971, the American Academy of Pediatrics found no medical need for routine circumcision. Nearly two decades later, in 1989, the group released updated guidelines suggesting that newborn circumcision has potential benefits. In 1999, it found insufficient evidence to recommend routine neonatal circumcision, leading Medicaid to stop covering the surgery in a number of states.

This position was then updated again in 2012 to reflect the organization's view that the health benefits outweigh the risks by possibly protecting against urinary tract infections, penile cancer, and some sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

The issue has not been revisited by the AAP for the last decade, an unusually long span, given that the organization usually reaffirms or updates existing guidelines every five years, said Freedman, the U.S. urologist. He suspects that the AAP might be "trying to just stay out of controversy for a little while." A spokesperson for the AAP said the organization was unable to comment.

WHEN THE American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidance in 2012, it was in the aftermath of the AIDS crisis, which was particularly devastating in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies from the region had suggested that circumcision could reduce a man's chances of contracting HIV from a virus-positive woman. Initially, the public health world was skeptical, but as the data rolled in, many embraced the findings. Mass circumcision campaigns were carried out in several countries, prompting at least one researcher to refer to "the studies that launched a thousand snips."

Robert Bailey, a professor emeritus of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Illinois Chicago, conducted some of the earliest research. In the late 1990s, he surveyed Ugandan men and found that circumcised men engaged in riskier sexual behavior than those who were uncircumcised. This was an unexpected result, as previous research had suggested that circumcised men had lower rates of HIV. Word of Bailey's findings spread to officials in Kenya, who invited him to work there. The situation in many communities was dire. Among the Luo people in the western part of the country, "38 percent of women coming to neonatal clinics were HIV positive," Bailey recalled. "It was just horrible."

Working in a city called Kisumu, Bailey and his colleagues designed a study that began with 2,784 uncircumcised, or intact, men age 18 to 24. About half were assigned to a control group and half were circumcised. Both groups received HIV testing and medical exams, and were interviewed every few months for two years. The results were so strong that the study ended early. Forty-seven uncircumcised men tested positive for HIV, compared with just 22 who were circumcised. "The protective effect of circumcision was 60%," Bailey and his colleagues wrote.

To spread the word, Bailey started giving talks. At first, the response was decidedly mixed. "I was ridiculed for this," he said. Some researchers, he recalled, literally laughed in his face.

But subsequent trials in other African countries reached similar conclusions, convincing policymakers to take action. Today, more than 25 million men in east and southern Africa have been circumcised as part of the World Health Organization's HIV prevention program. The Clinton Health Access Initiative, which carries out circumcisions in Zambia, cites research stating that between 2008 and 2019, the policy prevented 340,000 new infections.

Subsequent studies suggested that circumcision predominantly protected men who have sex with women from acquiring HIV. Male circumcision did not protect women from contracting HIV from their male partners, nor have studies conclusively shown that it shields men who have sex with men.

The reasons for these differences remain somewhat unclear. Andrew Harman, a virologist at the University of Sydney School of Medical Sciences, noted that HIV is transmitted in moist, permeable environments, similar to that of the foreskin. Circumcision exposes the head of the penis, called the glans penis, which is drier and more skin-like. This dryness may stifle virus replication and confer a measure of protection during vaginal sex, Harman said.

Anal sex is generally more abrasive than vaginal sex, scientists told Undark. That additional friction might explain why intact men who have sex with men don't experience a reduction in HIV transmission.

A 2022 study found circumcision did not protect against HIV in a population of more than 800,000 men born in Denmark between 1977 and 2003. Rates of syphilis, while very low, were also three times higher in circumcised men than the non-circumcised group. Additionally, the paper's lead author, Morten Frisch, a doctor and sexual health epidemiologist at the Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, argued that circumcision programs in Africa are unjustified nowadays, given the existence of new medications that dramatically reduce the risk of HIV infection.

The enormous resources spent over the past 15 years to promote male circumcision programs could have been directed towards other public health initiatives, Frisch wrote in an email to Undark. (He stressed that this was his own view and not that of his institution.)

Bailey described Frisch's paper as absurd. The vast majority of Denmark's HIV infections occur among men who have sex with men and among people who use injection drugs, he wrote in an email to Undark. Voluntary circumcision in adult men "is recommended for reduction of risk of HIV acquisition in HETEROSEXUAL men," he wrote. "In Africa most HIV infections are through heterosexual encounters unlike in Europe and the U.S." Other researchers have criticized Frisch's conclusions on similar grounds.

Some researchers say the benefits of circumcision go beyond HIV. For decades, Brian Morris, a professor emeritus at the University of Sydney, has worked to promote the health benefits of circumcision, which is only available in Australia at private health care clinics, where patients must pay for the procedure out of pocket.

Morris has likened circumcision to a vaccine, writing that the surgery is both low-risk and provides "enormous public health benefits." In his view, the benefits include a reduction in the risk of genital cancers, skin conditions, and various infections. Speaking with Undark, Morris described perspectives opposing male circumcision as propaganda.

It's "a real pity," he said. The procedure's opponents are fostering disease, suffering, and even death, he added. "They refuse to see the truth."

Other experts view Morris's position with a degree of skepticism.

Freedman, the U.S. urologist, said Morris is a solid scientist, but one who overstates the real-world implications of his findings. Consider penile cancer: Rates are quite low among intact men (in Ireland the disease affects roughly 1 in 66,000), and there are a variety of risk factors, including smoking and poor hygiene. Pediatric circumcision could reduce the incidence of penile cancer, said Freedman, but would it be worth the effort? To answer the question, one would have to weigh the benefits against the risk of medical complications while also considering a host of potentially important non-medical factors, such as culture, tradition, and respect for bodily autonomy. Ultimately, these are judgement calls that belong in the marketplace of ideas and the realm of persuasion, said Freedman.

Freedman recalled being on an Australian television show discussing circumcision. Morris represented the pro-circumcision view while another researcher opposed it. Freedman's view was somewhere in between. He doesn't believe that bans are justified, but he also said it's clear that circumcision is rarely medically necessary. When physicians are honest about this, he said, many parents decide not to circumcise their infants.

"IF YOU JUST do benefits and risks and some sort of medicalized calculus, you're missing the point," said Earp, the Oxford bioethicist. He is broadly opposed to any non-voluntary modification of genitals regardless of sex, on philosophical as well as medical grounds.

"Whose body is it?" he asked, speaking to Undark. "And who should get to decide?"

In 2022, Earp co-edited a special collection of papers that examined the cultural, legal, and ethical consequences of modifying an infant's body when that infant can't provide informed consent.

"And it's not just any part of their body," said Earp. "It's their sexual anatomy, which we're all taught we have a special dominion over and we have a special right to say no to."

In 2019, Earp and more than 90 colleagues, part of the Brussels Collaboration on Bodily Integrity, published a statement on genital cutting. It "brings together female, male, and intersex genital cutting and proposes a united ethical principle," he wrote to Undark. The document states that cutting a person's genitals without informed consent is "a serious violation of their right to bodily integrity."

"I think there are strong moral reasons to allow children of all family backgrounds (and sexes and genders) to be allowed to grow up free from genital cutting so they can make their own informed decision," he wrote by email. Translating these ideas into law without doing harm is not straightforward, he said. Education and raising awareness is vital so as not to inadvertently affect vulnerable or immigrant communities that practice circumcision. Earp added, "there are many social policy levers that can, and often should, be pulled to discourage problematic practices apart from blanket criminalization," which has been proposed in Denmark.

Muslims are the largest religious group to circumcise boys, a practice that dates back to the time of the Prophet Mohammad. In Islam, the procedure is viewed as an important religious ritual which also improves cleanliness. Circumcision is also traditionally understood as an obligatory practice in Judaism, where it marks the covenant between God and the Jewish people.

Anti-circumcision activists sometimes use language that touches on Islamophobic or antisemitic tropes, Osserman told Undark. He cited a comic book called Foreskin Man, which features a sinister-looking mohel, or person who performs Jewish circumcisions, and a blond superhero who comes to save the day. "That was just a very crass example of how antisemitic tropes can play out," said Osserman.

But opposition to the procedure isn't inherently antisemitic, said Norm Cohen. In 2014, Cohen, who is Jewish, founded the Intactivist Circle, which aimed to promote grassroots activism against circumcision of minors on the grounds that it causes pain and trauma. The group is no longer active, and Cohen now works at the state level as executive director of NOCIRC of Michigan, Inc. His organization was just one of several so-called intactivist groups, which have existed since the 1970s. They argue that circumcision is a medically unnecessary procedure that hurts infants without conferring benefits.

A software engineer by profession, Cohen has spent the past 30 years educating parents about the origins of circumcision. Victorian-era Americans, after all, were notoriously skittish about human sexuality, and the surgery was promoted as a way to reduce masturbation. The goal at the time was to "enforce moral cleanliness," said Cohen.

Cohen said this history was obscured from him while he was growing up, replaced instead with what he characterizes as dubious claims about disease prevention and a lack of physical harm to the penis. "Much of what I'd been taught about circumcision was wrong," he wrote to Undark. This realization "was followed by a period of anger about being harmed and cheated."

These days, people seem more willing to scrutinize the procedure and discuss it openly, said Cohen, noting that it's easier now to discuss sex in general.

For most of his adult life, Caddick suffered from phimosis, a condition in which the foreskin is tight and can't be pulled back. Phimosis is found in nearly all newborns, but usually gets looser in the early years. By adulthood, about 1 percent of men have the condition, which can cause swelling, soreness, and pain while urinating or having sex

"Nobody wants to go, 'Before we have sex there's like five things I need to tell you,'" said Caddick. "It kind of kills the mood."

In his 20s, he found that stretching exercises and prescription steroid cream could keep the problem at bay. But then he developed diabetes. Sugar would build up in his urine and get trapped beneath his foreskin, leading to painful infections and scarring. A urologist advised circumcision. The prospect was daunting. "If it wasn't for the medical issue, I think I'd have been too scared to go through with it," he told Undark.

The procedure took 30 minutes, recalled Caddick. It was conducted under a local anesthetic, with a medical curtain to conceal his view of the cutting. He was then sent home with a packet of bandages and instructions to take an over-the-counter medicine if he felt any pain.

Recovery wasn't simple, however, as adults usually experience more side-effects than newborns. His skin was blotchy and swollen. He worried it might not return to normal.

A Reddit group devoted to adult circumcision is full of such concerns, with men asking each other questions like "5 months: What can I do to reduce further swelling?" Some people heal quickly, while others take more time. In a post from a couple of years back, one man complains of problems two years after his surgery. In a different post, someone notes that there is "definite loss of sensitivity" and men need to relearn "how you jerk off and how you have sex."

Caddick did recover, although he said it will be several months before the scarred skin is flexible again, and now says he wishes he'd had the procedure when he was younger: It would have given him more confidence. "I feel a lot more optimistic about sex in the future," he said, "even at 48."

While some men in the Reddit group get circumcised because of phimosis, others do it for aesthetic reasons. Some write of longing to be circumcised, of carrying the procedure in the back of their mind for years. One person wrote to Undark that circumcision made his penis more visually appealing, and "was simply a worthwhile and easy personal improvement."

Another posted, "It's an upgrade, trust me."

Still, other men say sex is better with a foreskin. "I hope your publication is interested in reporting the very specific and explicit reasons sex is better when the normal slack skin is present," Ron Low wrote by email. As Low explains it, the skin of a circumcised penis creates friction, lacks sensitivity, and has lost a key function: An intact penis' slinky sheath leads to a unique gliding action during sex, he said.

Low was working as an industrial engineer in 2003, when he created a device to restore the foreskin. TLC Tugger, as it's now known, includes a funnel-shaped piece of silicone that sits snuggly against the glans. Users stretch their remaining shaft skin over the silicone shell and secure it to the user's knee using a tugging strap, applying a "constant gentle tension" that slowly stretches the skin.

According to Low, the gentle tugging promotes the growth of new skin cells. Regrowing a full foreskin can take about 5 years. "It's so gentle that you could forget you're wearing it," said Low, who said he still wears his at night.

The TLC Tugger kit costs around $80 to $90 and is sold on a buyer-beware basis, similar to other non-medical devices, including penis extenders and sex toys, wrote Low in response to an Undark query. Since 2008, he said, his family has lived off the proceeds. Foreskin restoration tools, in fact, have become a cottage industry. Etsy offers an array of devices: a silicone retainer "with a frenulum notch" (a bestseller), the PeckerPacker starter kit, or the phimosis wearable manual stretcher for extending tight foreskin.

Christoph Kupferschmid, the German pediatrician, has known some men who used such devices. Skin can be stretched, he said, "but you don't get back the nerves. You can pull on those nerves that are there, but you don't get back what is cut off."

Jennifer Bossio, a clinical psychologist and adjunct professor at Queen's University in Ontario, has conducted studies to better understand how circumcision may influence genital sensation as well as a person's sex life. These questions intrigued her because "the existing research on the topic was fraught with bias," she wrote to Undark, adding that she felt her academic training would give her a neutral perspective on the topic.

For one study, published in 2016, Bossio and her co-authors exposed circumcised and uncircumcised men to tactile, pain, and thermal stimuli. There was no difference between the two groups, leading the authors to conclude that neonatal circumcision had "minimal long-term implications" for penile sensitivity.

When it comes to the sexual satisfaction of men's partners, some of Bossio's research indicates that gay men have a strong preference for intact penises while women have a slight preference for circumcised penises; but both groups reported being satisfied regardless of their partner's circumcision status.

Bossio said that after she published her 2016 paper, she was harassed by intactivists for years. "Had I known how politically charged the topic was," she wrote in an email, "I am not sure I would have embarked on the research."

Asked whether distress among circumcised men appeared to be rising, Bossio said there isn't enough data to say. "It's not all neonatally circumcised men who express high levels of distress. From what I can gather, there is a very small group of men who were neonatally circumcised who are highly distressed, and quite vocal online about it." Research on how circumcision status affects a man's sex life is inconclusive, she wrote, with some studies reporting that it decreases sexual function, others suggesting it improves it.

Bossio said that in her clinical practice, she is more likely to encounter men struggling with phimosis than with their circumcision negatively impacting sexual function.

IN THE U.S., newborn circumcision rates fell from 65 percent in 1979 to 58 percent in 2010. In states where Medicaid no longer covers the procedure, rates have dropped precipitously. Out-of-pocket rates range from $500 for newborn circumcisions to $3,500 for adults, according to one website.

The country could soon reach a tipping point, said Earp. Once the procedure becomes less common, parents will stop choosing the surgery as the default, thus pushing rates even lower.

As circumcision rates in the U.S. decline, clinicians will encounter more and more uncircumcised penises. There remains a lack of knowledge about intact penises even among pediatricians, however, who are busy and sometimes squeamish, Freedman observed.

At birth, a male baby's foreskin is attached to the head of the penis. Over the next few years, the foreskin begins to loosen and can be pulled back, or retracted, in order to clean the area. In the past, practitioners advised parents to retract the foreskin forcefully, or did it themselves. In 2022, the AAP published a patient education document on the correct care of the intact penis. It states that "Forcing the foreskin to retract before it is ready can cause severe pain, bleeding, and tears in the skin."

When caregivers push back the foreskin of a child's penis, they also risk tearing the skin and causing long-term damage. John Geisheker, the executive director of Doctors Opposing Circumcision, told Undark that he had personally treated more than 1,500 cases of boys injured by forcible retraction in a medical setting. "Forcible retraction before age 10 is invariably an injury," he wrote by email. Instead, the recommendation is to more or less leave the area alone.

Greater awareness may be needed based on current trends, said Freedman, adding that he'd be glad to work with anti-circumcision activists to spread knowledge on this issue. He takes issue with what he believes is an all-too-common notion that everyone should be circumcised.

In an ideal world, he said, all penises — intact and circumcised — would be welcome.

Reader Comments

Go figure.

LOL, I mean HEH HEH hEH...

Wonder if there's a connection....[Link]

''We were told that while male circumcision was legal under all circumstances in Canada, any attempt to study the adverse effects of circumcision was strictly prohibited by the ethical regulations.''

My question is a simple one: Why not ? Legal does not mean without adverse effects, as the one time study proved. It could be argued only one study / observation does not constitute a proof but does that not indicate there might, just might, be something there? My money is on the usual suspects since it is a part of their way of life they try hard to impose on all of us.

Circumcision is a symbolic castration marking one as a member of a domesticated slave race.

i.e. It won't make you infertile, but it's likely to disable certain functions within the human machine.

Or so it seems to me, anyway.

Why would a Yehudi or Egyptian sky dude want to disable certain functions in the human machine amongst whatever chosen tribe?

Domination, most likely.

Or so it seems to me, anyway.

I did try and do some research about acupuncture meridians and the foreskin.

Couldn't find anything on it.

Or anything about acupuncture meridiens and genitalia.

Which is bizarre, 'cause you'd think if anywhere was gonna be a massive junction box of bio-electrical meridiens, it would be the sex parts.

Now, as to why cut guys might think uncut guys are gross? Smegma. That buildup under the foreskin you get if your parents don't teach you personal hygiene because talking about it is uncomfortable for them. In fact, I would guess that deep down, the majority of parents who chose circumcision for non-religious reasons are choosing it so they don't have to have that uncomfortable conversation and making every other excuse for it.

And as for Tyler Durden seasoning the chicken parmigiana..

If God didn't chose the chosen people, who inherited that rulership? And how would Americans generally fall into the category of privileged slave when on average, Americans as a whole are the 1% of the world's wealth and status?

Remember, you TL;DR'd the article, which means you're arguing from a different premise than everyone who actually read the article, which discusses at length how many times this argument over to snip or not to snip has been going on and how heated the topic can get, that's without introducing shades of Grand Ancient Conspiracy.

Whatever the origins of and true reasons for circumcision, they are probably antediluvian in origin and lost like so much else 13kya.

Phimosis isn't a reason to hurt babies. But for a proper age, I might presume ear stretchers and some cream should be the first option?

I think they must be lying about circumcision preventing HIV, unless intact males are more susceptible for unscientific reasons.

The god of the old testament was created to keep a population in line and was, like in any religion, coopted by so-called demonic entities. These entities continue to traumatize children today, usually through sex and negative imagery.

Stopping maturbation sounds like a lost cause, even if it were beneficial.

When a baby is circumcised, some ritual Jewish circumcisers (mohelim) do a practice called metzitzah b’peh. Metzitzah b’peh is when the mohel uses their mouth to suck blood away from the baby’s circumcision wound as part of the circumcision ritual. [Link]

[Link]

They belong in hell.

To that end, women are morons.

Are you stupid?

Or what?

ned

It always pays to argue.

It always pays.

It always pays to argue over which form of violence/mutilation/torture is best.

To serve the needs of the 'moral majority'...the 'superior clan'...THE CHOSEN ONES.

Duh.

FUCKNG FUCKING FUCKING DUH.

ned,

out

Circumcisionno it should be called by what it is without a euphemism: genital mutilation that should be outlawed. If someone turns 16 or so and wants it done or if there is actually some medical need then whatever but doing it to babies is just sick. Men have foreskins for a reason, if not, why would they be there?Pervo bizarro, eh?