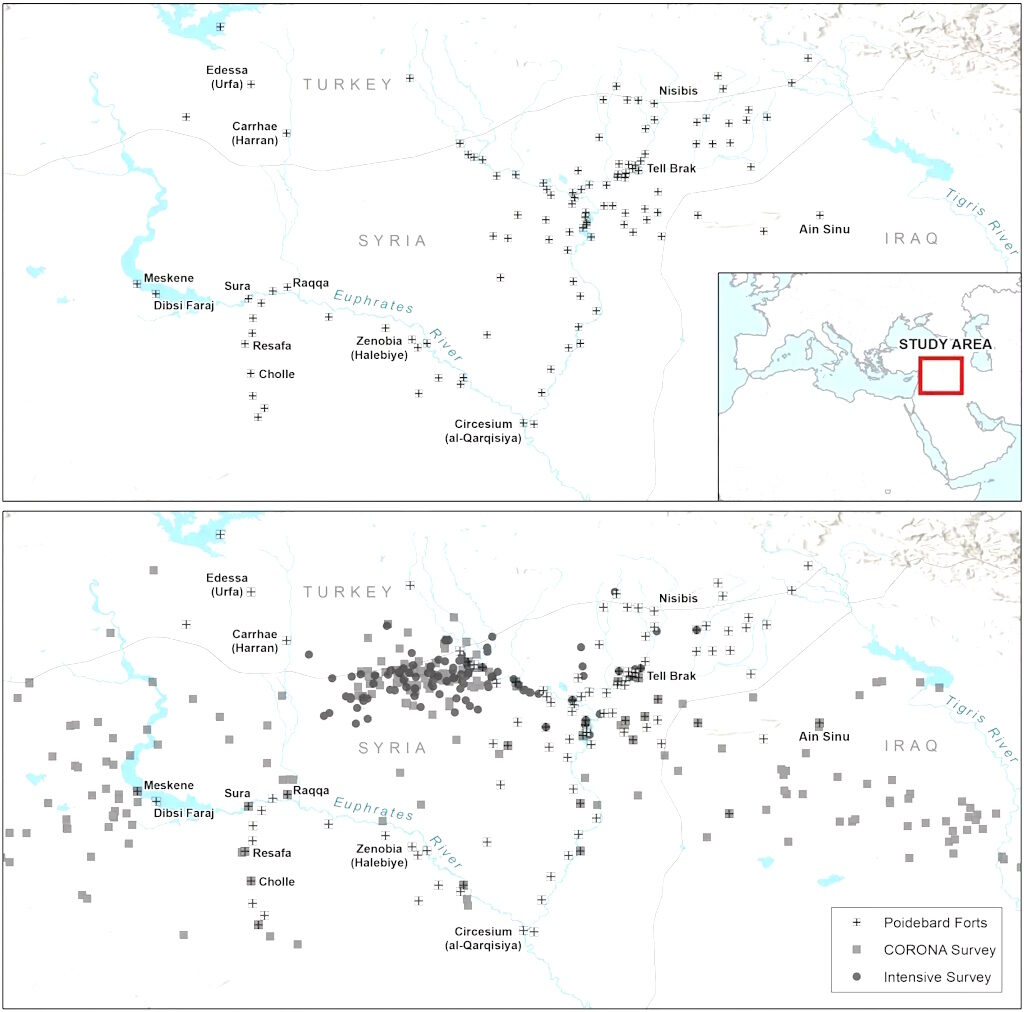

Examining declassified spy satellite imagery collected from the 1960s to late 1980s, a team of archaeologists from Dartmouth College say they identified 396 lost ancient Roman fortresses across the landscapes of present-day Syria and Iraq.

Experts say the findings, published in the journal Antiquity, upend long-standing beliefs about the Roman Empire's eastern frontiers and the relationship between the Western and Eastern culture during antiquity.

"Since the 1930s, historians and archaeologists have debated the strategic or political purpose of this system of fortifications," wrote study authors. "But few scholars have questioned Poidebard's basic observation that there was a line of forts defining the eastern Roman frontier."

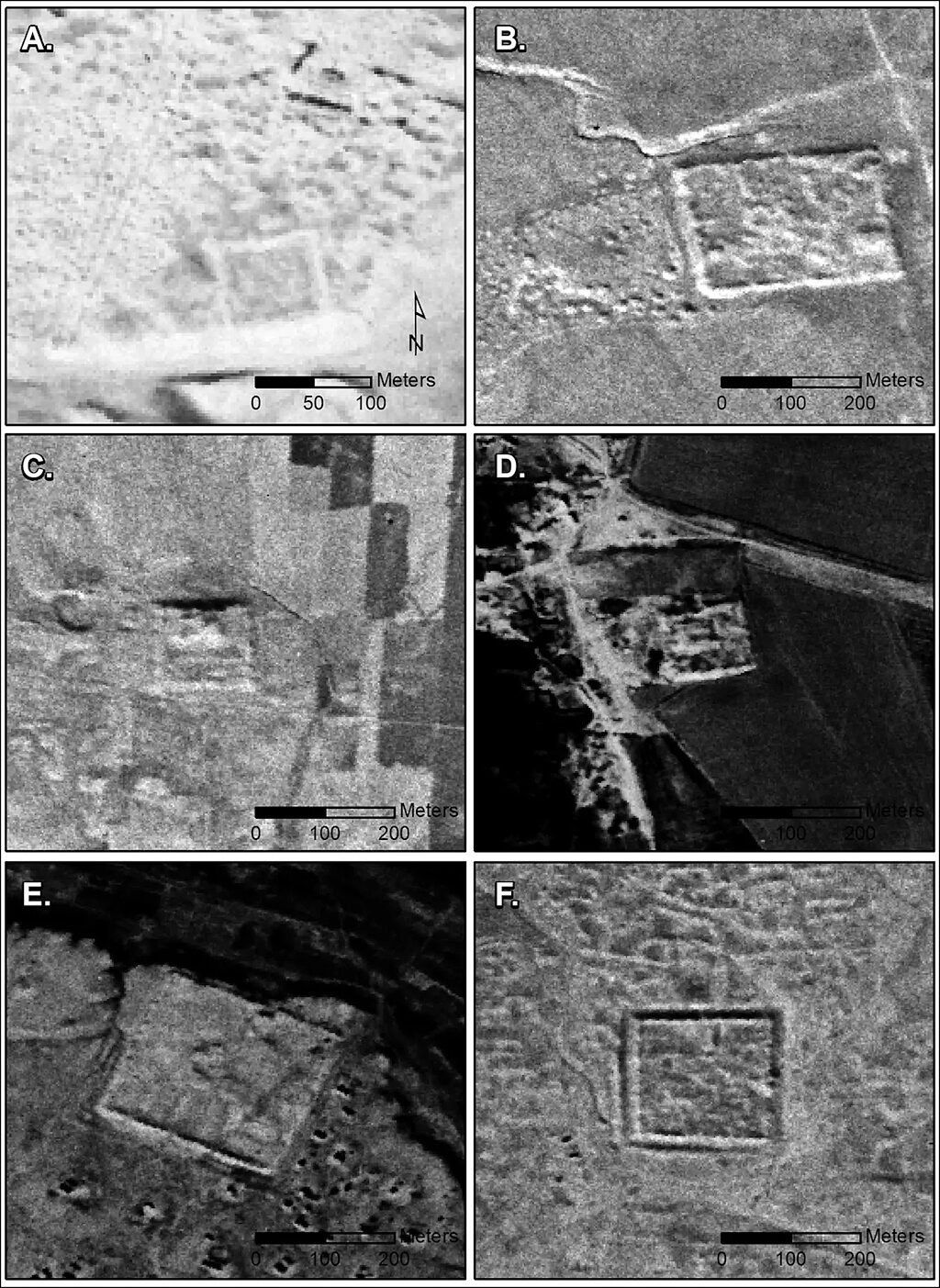

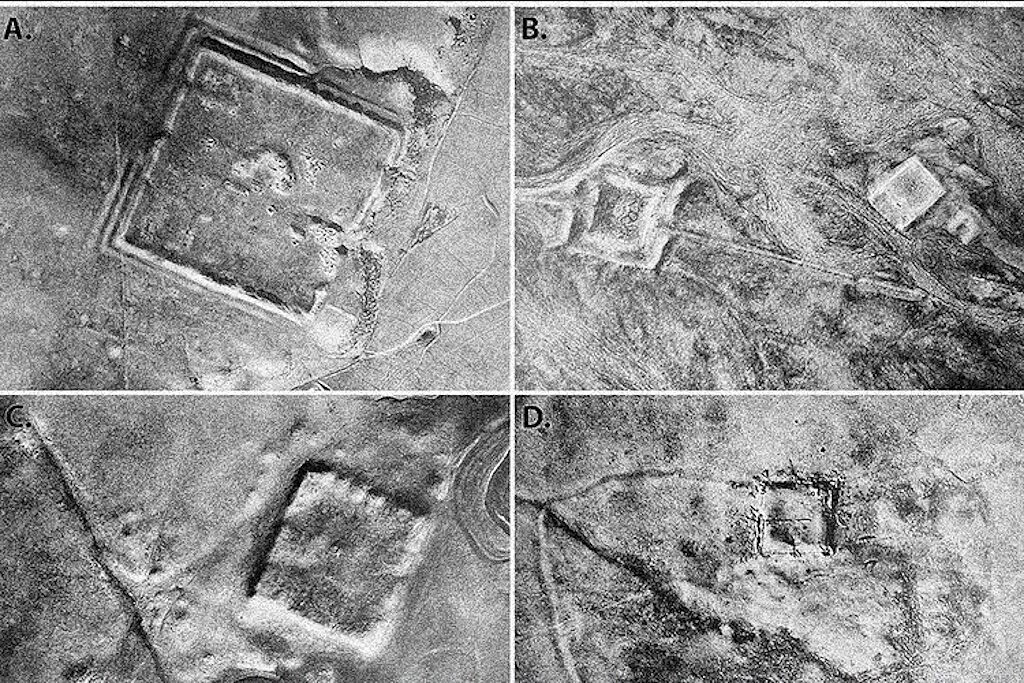

Leveraging declassified imagery from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and National Reconnaissance Office's (NRO) CORONA and HEXAGON spy satellite programs, a team of Dartmouth archaeologists, led by Dr. Jesse Casana, discovered hundreds of previously lost Roman forts, not originally surveyed by Father Poidebard.

The high-resolution images captured by the pioneering spy satellite programs allowed researchers to propose a new narrative of Roman strategic placement in the region.

"I was surprised to find that there were so many forts and that they were distributed in this way because the conventional wisdom was that these forts formed the border between Rome and its enemies in the east, Persian or Arab armies," Dartmouth professor of archeology and lead author, Dr. Jesse Casana said. "While there's been a lot of historical debate about this, it had been mostly assumed that this distribution was real, that Poidebard's map showed that the forts were demarcating the border and served to prevent movement across it in some way."

The discovery challenges the traditional image of Roman borders as heavily militarized zones, suggesting the Eastern Roman frontiers were far more focused on commerce and cooperation than previously thought.

"The distribution of these forts suggests that they did not function as a border wall, with a series of towers and fortified encampments designed to block westward incursions by Persian armies or to prevent raids on agricultural villages by nomadic tribes," researchers write.

"Instead, our findings strengthen an alternative hypothesis that such forts supported a system of caravan-based interregional trade, communication, and military transport."Using dating evidence from recent excavations and surveys of the region, researchers believe most of the newly rediscovered Roman forts were constructed and used between the second and sixth centuries AD. Many sites would have been large enough to accommodate soldiers, horses, or camels.

"As recent scholarship reimagines Roman frontiers as sites of cultural exchange rather than barriers, we can similarly view the forts of the Syrian steppe as enabling safe and secure transit across the landscape, offering water to camels and livestock, and providing a place for weary travelers to eat, drink and sleep, thereby playing a critical role in bringing east and west together."

Most of the forts were constructed of stone or entirely out of mud-brick. Researchers say after 1,500 years of being exposed to the elements, the latter structures have likely "melted into the ground."

Archaeologists could only locate 38 of the 116 Roman forts originally documented by Father Poidebard. Researchers say many of these sites have likely been destroyed or obscured by modern land development. Because of this, the CORONA and HEXAGON imagery serves as an indispensable record for these historical sites.

Ultimately, researchers say their recent work showcases the remarkable interplay between technological advancement and historical exploration. It also underscores the potential for spy satellite imagery to reshape historical understandings.

"The discovery of such a large number of previously undocumented ancient forts in this well-studied region of the Near East is a testament to the power of remote-sensing technologies as transformative tools in contemporary archaeological research," researchers wrote.

"As more declassified and historical imagery becomes available, including still underutilized resources such as HEXAGON imagery, U2 spy plane imagery, and other forms of early twentieth-century aerial photography, careful analysis of these powerful data holds enormous potential for future discoveries in the Near East and beyond."

Tim McMillan is a retired law enforcement executive, investigative reporter and co-founder of The Debrief. His writing covers defense, national security, and the Intelligence Community. You can follow Tim on Twitter: @LtTimMcMillan. Tim can be reached by email: tim@thedebrief.org or through encrypted email: LtTimMcMillan@protonmail.com

Reader Comments