The passage of time has not left me any less angry about lockdowns. My blood still boils when I think of the unnecessary suffering: the broken homes and broken businesses; the lost last moments with loved ones; the missed cancers and operations; a generation of children scarred forever.

This country paid a catastrophic price for what I see as a reckless overreaction to a disease that was only life-threatening to a small number of people who could have been protected without imprisoning the entire population. As each day passes, more evidence emerges that shutting down society for prolonged periods to 'stop the spread' and 'protect the NHS' was a monumental disaster.

Hancock, obviously, disagrees. The Rt Hon Member for West Suffolk is not just unrepentant: he still wholeheartedly believes that as health secretary during the pandemic, he made all the right calls. He is utterly scathing of anyone who argues that repeated lockdowns were avoidable; does not have the slightest doubt over any aspect of the government's vaccine policy; and thinks anyone who believes any other approach to the pandemic was either realistic or desirable is an idiot.

How then could I have worked with him on his book about the pandemic? Some of my lockdown confidantes suggested it was a betrayal and that he should be punished, perhaps viciously so.

Well, hold on a minute. Journalists don't only interrogate people they agree with. Quite the reverse. I wanted to get to the truth. What better way to find out what really happened - who said what to whom; the driving force and thinking behind key policies and decisions; who (if anyone) dissented; and how they were crushed - than to align myself with the key player? I might not get the whole truth and nothing but the truth, but I'd certainly get a good dollop of it, and a keen sense of anything murky requiring further investigation.

In the event, Hancock shared far more than I could ever have imagined. I have viewed thousands and thousands of sensitive government communications relating to the pandemic, a fascinating and very illuminating exercise. I was not paid a penny for this work, but the time I spent on the project - almost a year - was richly rewarding in other ways. Published this week, co-authored by me, Hancock's Pandemic Diaries are the first insider account from the heart of government of the most seismic political, economic and public health crisis of our times.

I am not so naive as to imagine that he told me everything. However, since he still does not believe he did anything wrong, he was surprisingly inclined to disclosure. In an indication of how far he was prepared to go, the Cabinet Office requested almost 300 deletions and amendments to our original manuscript. Under pressure from me and out of his own desire that the book should be both entertaining and revelatory, to his credit, Hancock fought hard to retain as much controversial material as he could. The resulting work is twice as long as I originally intended, and half the length he wanted it to be. His desire to make it a book of record and mine to do journalistic justice to the sensational raw material he shared with me led to periodic creative differences. At times I pushed him further than he wanted, while I was forced to accept the watering-down of some material.

Amid the furore over his I'm a Celebrity antics, the ongoing media fascination with his lockdown rule-breaking sexual shenanigans, and the natural scepticism of his critics about anything he says, there is a danger that some of what we have learnt about the government's response to the pandemic is lost. Here then — based not only on what is in the Pandemic Diaries but on everything I saw in the process of putting the book together — are what I consider the key lessons.

Vaccine policy

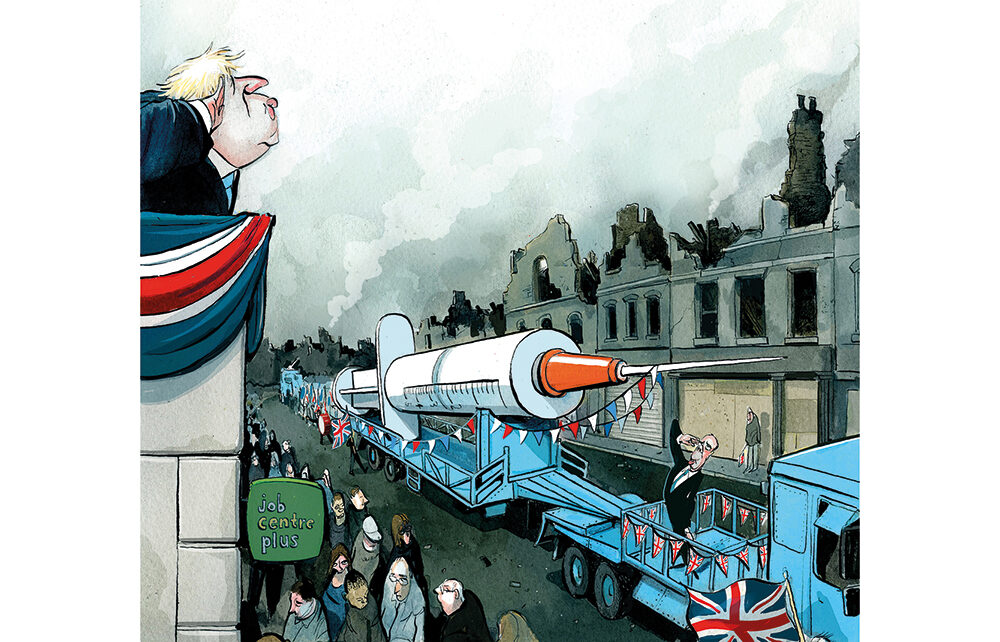

The crusade to vaccinate the entire population against a disease with a low mortality rate among all but the very elderly is one of the most extraordinary cases of mission creep in political history. On 3 January 2021, Hancock told The Spectator that once priority groups had been jabbed (13 million doses) then 'Cry freedom'. Instead, the government proceeded to attempt to vaccinate everyone, including children, and there was no freedom for another seven months. Sadly, we now know some young people died as a result of adverse reactions to a jab they never needed. Meanwhile experts have linked this month's deadly outbreak of Strep A in young children to the weakening of their immune systems because they were prevented from socialising. Who knows what other long-term health consequences of the policy may emerge?

Why did the goalposts move so far off the pitch? I believe multiple driving forces combined almost accidentally to create a policy which was never subjected to rigorous cost-benefit analysis. Operating in classic Whitehall-style silos, key individuals and agencies - the JCVI, Sage, the MHRA - did their particular jobs, advising on narrow and very specific safety and regulatory issues. At no point did they all come together, along with ministers and, crucially, medical and scientific experts with differing views on the merits of whole-population vaccination, for a serious debate about whether such an approach was desirable or wise.

The apparent absence of any such discussion at the top of government is quite remarkable. The Treasury raised the occasional eyebrow at costs, but if a single cabinet minister challenged the policy on any other grounds, I've seen no evidence of it.

In Hancock's defence, he would have been crucified for failing to order enough vaccines for everybody, just in case. He deserves credit for harnessing the full power of the state to accelerate the development of the Oxford/AstraZeneca jab. He simply would not take no or 'too difficult' for an answer, forcing bureaucratic regulators and plodding public health bodies to bend to his will. He is adamant that he never cut corners on safety, though the tone of his internal communications suggest that in his hurtling rush to win the global race for a vaccine, he personally would have been willing to take bigger risks. I believe he would have justified any casualties as sacrifices necessary for the greater good. Fortunately (in my view) his enthusiasm was constrained by medical and scientific advisers, and by the Covid vaccine tsar Kate Bingham, who was so alarmed by his haste that at one point she warned him that he might 'kill people'. She never thought it was necessary to jab everyone and repeatedly sought to prevent Hancock from over-ordering. Once he had far more than was needed for the initial target group of elderly and clinically vulnerable patients, he seems to have felt compelled to use it. Setting ever more ambitious vaccination rollout targets was a useful political device, creating an easily understood schedule for easing lockdown and allowing the government to play for time amid the threat of new variants. The strategy gave the Conservatives a big bounce in the polls, which only encouraged the party leadership to go further.

Side-effect monitoring

Given the unprecedented speed at which the vaccine was developed, the government might have been expected to be extra careful about recording and analysing any reported side-effects. While there was much anxiety about potential adverse reactions during clinical trials, once it passed regulatory hurdles, ministers seemed to stop worrying. In early January 2021, Hancock casually asked Chris Whitty 'where we are up to on the system for monitoring events after rollout'.

Not exactly reassuringly, Whitty replied that the system was 'reasonable' but needed to get better. This exchange, which Hancock didn't consider to be of any significance, is likely to be seized on by those with concerns about vaccine safety.

Scotland

One of the most striking themes to emerge from internal communications is the scale of concern about Scotland. 'WE MUST NOT LET THE SCOTS HAVE THEIR OWN VACCINE PASSPORTS. STOP THIS MADNESS NOW,' Boris Johnson implored, in one of his most agitated messages with Hancock.

Right from the start, Downing Street was terrified that the virus might somehow accelerate the break-up of the Union. As early as 12 March 2020, Hancock made the effort to fly up north to talk to Scottish health ministers in person, observing that Nicola Sturgeon 'would not be able to resist' exploiting the crisis to push for Scottish independence ('so we need as much amicable cooperation as possible').

In the months that followed, an inordinate amount of time was spent second-guessing the First Minister and trying to stop her blindsiding the UK government. Cobra meetings became a real problem. Describing her modus operandi in these top secret discussions, Hancock says she would 'sit like a statue, lips pursed like a drawstring bag, only jolting into life when there's an opportunity to say something to further the separatist cause'. The minute meetings ended, he claims, you could 'almost hear her running for a lectern so she can rush out an announcement before we make ours'. After a while, ministers avoided debating the most sensitive issues in this forum for fear of leaks.

Throughout the pandemic, far-reaching policy decisions, especially international travel restrictions and the timing of lockdowns, were distorted by what Sturgeon was doing or what No. 10 feared she might do. Hancock describes her move to mandate mask-wearing in secondary schools in late August 2020 as 'one of her most egregious attempts at one-upmanship to date', admitting the UK government was left 'scrabbling around to formulate a response'. The UK government's own guidance on face coverings had specifically excluded schools. Faced with an unpleasant choice between wheeling out the chief medical or scientific officer to say that the Scots were wrong or performing a U-turn, Downing Street chose the latter. That, rather than any medical reason, is why millions of schoolchildren were forced to spend months with grubby bits of material stuck to their faces.

More positively, ministers worked hard to use the vaccine rollout to reinforce Union ties. Very early on, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace suggested there should be a Union Jack on all packaging. Hancock repeatedly tried to persuade regulators to let the government brand the Oxford/AstraZeneca jab in this way.

The dissenters

As far as Hancock was concerned, anyone who fundamentally disagreed with his approach was mad and dangerous and needed to be shut down. His account shows how quickly the suppression of genuine medical misinformation — a worthy endeavour during a public health crisis — morphed into an aggressive government-driven campaign to smear and silence those who criticised the response. Aided by the Cabinet Office, the Department of Health harnessed the full power of the state to crush individuals and groups whose views were seen as a threat to public acceptance of official messages and policy. As early as January 2020, Hancock reveals that his special adviser was speaking to Twitter about 'tweaking their algorithms'. Later he personally texted his old coalition colleague Nick Clegg, now a big cheese at Facebook, to enlist his help. The former Lib Dem deputy prime minister was happy to oblige.

Such was the fear of 'anti-vaxxers' that the Cabinet Office used a team hitherto dedicated to tackling Isis propaganda to curb their influence. The zero-tolerance approach extended to dissenting doctors and academics. The eminent scientists behind the so-called Barrington Declaration, which argued that public health efforts should focus on protecting the most vulnerable while allowing the general population to build up natural immunity to the virus, were widely vilified: Hancock genuinely considered their views a threat to public health.

For his part, Johnson occasionally fretted that they might have a point. In late September 2020, Hancock was horrified to discover that one of the architects of the Declaration, the Oxford epidemiologist Professor Sunetra Gupta, and Professor Carl Heneghan, director of the University of Oxford's Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, had been into Downing Street to see the prime minister. Anders Tegnell, who ran Sweden's light-touch approach to the pandemic, attended the same meeting. Hancock did not want them anywhere near Johnson, labelling their views 'absurd'.

Care homes

Hancock is more sensitive about this subject than any other. The accusation that he blithely discharged Covid-positive patients from hospitals into care homes, without thinking about how this might seed the virus among the frail elderly, or attempting to stop this happening, upsets and exasperates him. The evidence I have seen is broadly in his favour.

At the beginning of the pandemic, it was simply not possible to test everyone: neither the technology nor the capacity existed. Internal communications show that care homes were clearly instructed to isolate new arrivals. It later emerged that the primary source of new infection in these settings was in any case not hospital discharges, but the movement of staff between care homes. Politically, this was very inconvenient: Hancock knew he would be accused of 'blaming' hardworking staff if he emphasised the link (which is exactly what has now happened).

He is on less solid ground in relation to the treatment of isolated care-home residents and their increasingly desperate relatives. His absolute priority was to preserve life — however wretched the existence became. Behind the scenes, the then care home minister Helen Whately fought valiantly to persuade him to ease visiting restrictions to allow isolated residents some contact with their loved ones. She did not get very far. Internal communications reveal that the authorities expected to find cases of actual neglect of residents as a result of the suspension of routine care-home inspections.

Masks

Hancock, Whitty and Johnson knew full well that non-medical face masks do very little to prevent transmission of the virus. People were made to wear them anyway because Dominic Cummings was fixated with them; because Nicola Sturgeon liked them; and above all because they were symbolic of the public health emergency.

As early as 3 February 2020 - long before anyone outside the Department of Health was taking the prospect of a pandemic seriously - ministers were told the masks make no significant difference. In April 2020, the New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (Nervtag) reiterated this advice. At the end of that month, the Sage committee said much the same thing, telling ministers that it would be unreasonable to claim a large benefit. An 'obsessed' Cummings was the driving force behind mandating mask-wearing in all healthcare settings - and then in retail and hospitality. On 28 June he messaged Hancock to complain that the government was being insufficiently 'aggressive' on the issue and demanding that they be compulsory in shops and for restaurant staff.

In a private exchange with Hancock, Whitty said he could see 'no scientific or medical reason not to' make them compulsory. He described the evidence in favour of mask-wearing as 'moderate' in general but 'positive in enclosed spaces where distancing is difficult'. Hancock's response? 'I said I could see no reason not to use the power of the state to enforce it and that the importance of masks should be in all our messaging.' That summer, the Treasury was instructed to change a planned advertising campaign (designed to get punters back into pubs) to ensure all models featured were masked up.

Cancer

During the pandemic there were tens of thousands of missed cancer diagnoses. As the NHS morphed into a 'Covid service', there seems to have been remarkably little discussion at the top of government about the risk of compromising standards of care for people with other serious illnesses. A year into the pandemic, Johnson messaged Hancock saying he'd been reading an uplifting book about cancer (The Emperor of All Maladies by Siddhartha Mukherjee) and suggesting Hancock lead a 'moonshot' effort to turn cancer into a survivable disease when the crisis was over, something the pair had discussed when Johnson became PM. Sadly, lockdowns made that a far more distant goal. In a diary entry in May 2020, Hancock reveals concerns that hospitals had neither the technology nor expertise to treat cancer patients in a way that didn't increase their chances of dying of Covid. It was feared chemotherapy would make them more vulnerable to the disease, so hospitals were supposed to switch to radiotherapy. It now transpires they didn't have the necessary kit.

Hancock admits the NHS misled patients about this sorry state of affairs by declaring everything was fine. 'In reality, as I learned today, our equipment is not suited to the type of radiotherapy that's being recommended, not least because it was generally installed ten years ago. There are also concerns about whether staff have the required expertise. I can't quite believe we're having this problem,' he says gloomily. Those affected, and their families, may never forgive the fact that the treatment of people with conditions that were certainly life-threatening was so hampered by the effort to ensure healthy people didn't contract a virus that was far less likely to kill them. Meanwhile, clinical trials for almost everything except the Covid vaccine collapsed. To his credit, Lord Bethell, then a health minister, repeatedly pushed for a return to 'business as usual'.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that Hancock worked phenomenally hard to do what he felt was best, based on all the information available at the time. Day after day, he was forced to make tremendously difficult judgments, balancing sharply competing interests. The number of critical decisions he was required to make, edits and instructions he had to issue, meetings he had to attend and calls he had to field would have tested anyone to their limits - and did. While vast sums of public money were wasted and the collateral damage from lockdowns and other Covid policies was enormous, I do not believe there was any kind of conspiracy, still less any malign intent on the part of our political leaders during the crisis. They may have been misguided; and got some things catastrophically wrong, but mistakes were made in good faith. Whether or not those errors will be forgiven by a public only just beginning to realise the full consequences is another question.

Isabel Oakeshott is a former Political Editor of the Sunday Times and is now International Editor of Talk TV

Comment: Though Oakshott has more or less crafted an apologia for Hancock, it is still an interesting glimpse behind the government scene in the U.K. Hysteria and individual political ambitions seems to have driven most of the decisions.