Millions of dollars were flowing into its U.S. headquarters for a business owned by the oligarch, but something wasn't right. Detecting signs of suspicious money — large round numbers from high-risk jurisdictions — the bank could have refused the transfers or even dropped the client.

But it didn't do either.

Despite warnings from its own workers, Deutsche allowed the money to keep pouring into its coffers six years ago while the oligarch and his partners secretly amassed a steel fortune in the United States.

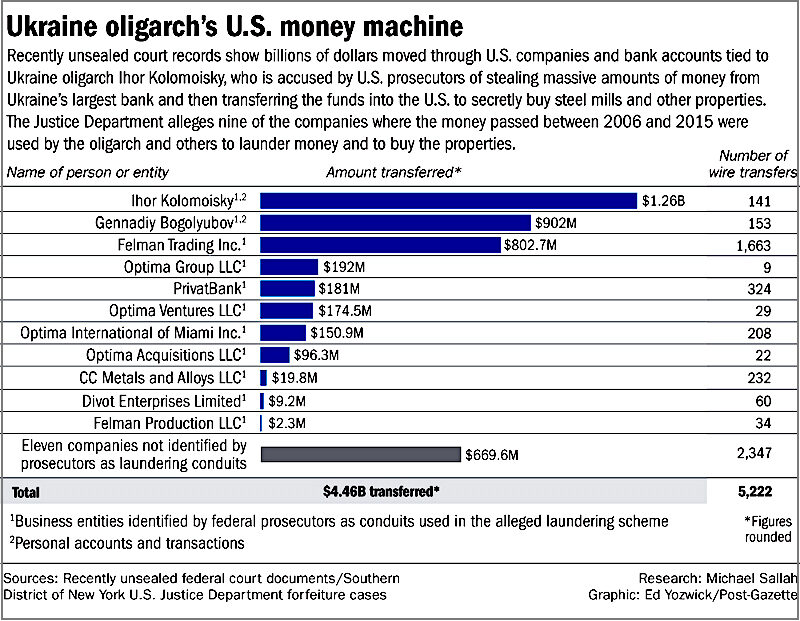

The Justice Department has been investigating Mr. Kolomoisky and others in what prosecutors allege was a vast scheme to steal millions of dollars from Ukraine's largest bank and move the money into the U.S. to buy steel mills and skyscrapers.

But recently unsealed federal court records show U.S. banks moved far more money than what was reported by the U.S. government — billions of dollars — for companies under the control of the power broker in patterns that went unchecked for nearly a decade.

Between 2006 and 2015, more than $4.45 billion was transferred without any apparent effort by the banks or the government to stem the movement of dollars as the oligarch and his partners acquired an enormous real estate portfolio.

Tom Cardamone, president and CEO of Global Financial Integrity, a Washington, D.C., research group that tracks money laundering, said:

"These are cascading failures. It's an astonishing amount of money. You would think that anyone just doing a spot check, someone would have picked up on the tempo of the transactions, the big round numbers."The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has spent more than a year examining thousands of records — including internal bank documents and previously sealed court records — and conducted dozens of interviews that culminated in several stories about federal prosecutors' first-ever laundering investigation of the U.S. steel industry.

But the new records released last month from federal court in New York provide an unprecedented look into the amount of money tied to the oligarch that was moving through the country — including thousands of transactions carried out by Deutsche, Germany's largest bank with a sizable U.S. arm.

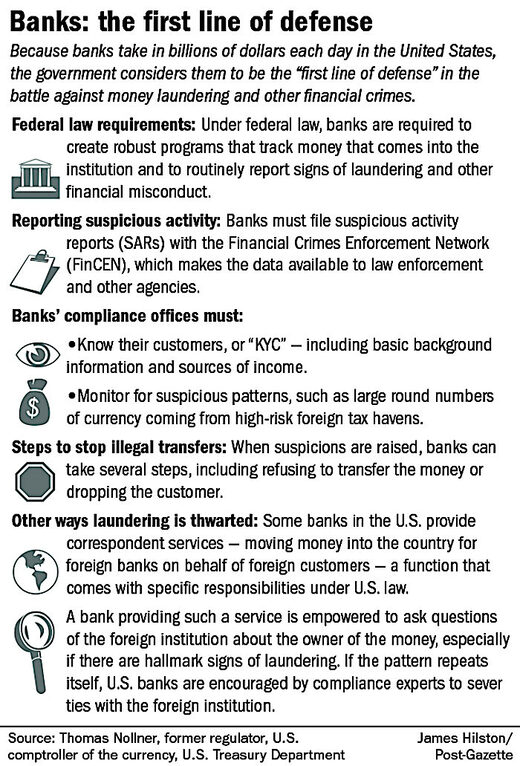

In the government's battle against money laundering, banks are supposed to be the front line of defense by alerting the government when it spots suspicious patterns and, in some cases, refusing the transactions, says the U.S. Justice Department.

But records show that year-after-year, the transfers continued while prosecutors say Mr. Kolomoisky orchestrated a scheme that nearly bankrupted Ukraine's largest financial institution and sent the nation's economy into a recession.

Left trail of disaster

One of the richest men in Ukraine, the 59-year-old oligarch is accused of setting up shell companies, cleaning the money through U.S. properties and ultimately leaving a trail of boarded-up buildings, failed steel facilities, and millions in unpaid property taxes, court records show.

While money was transferred into the country for one of the oligarch's companies, his operators shut down Warren Steel in Ohio in 2016, owing millions in property taxes, utility bills and supplies.

For weeks, workers were left without medical coverage because the insurance premium wasn't paid, records and interviews show. "A lot of people left here very angry," said Nancy Waselich, a former IT manager for the factory. "People bled for this place."

Though no one so far has been criminally charged, prosecutors have filed legal actions to seize properties that they allege were bought with money stolen from the Ukraine bank, where Mr. Kolomoisky was a major shareholder. The oligarch lost control of the institution in late 2016, when it was nationalized by the government, which suspected massive fraud.

Lawyers for two of Mr. Kolomoisky's partners in the U.S. who are accused in the government forfeiture cases of taking part in the scheme say there is no evidence to show they did anything wrong.

Mordechai "Motti" Korf and Uriel Laber, who live in South Florida, are "legitimate investors," said New York attorney Mark Ressler. Neither has been

"engaged in money laundering of any kind, and they have no knowledge of anyone else doing so. Any allegations against Mr. Korf and Mr. Laber arise from Ukrainian political disputes they have nothing to do with."Lawyers for the two men dispute the U.S. government's claims the money was stolen from the Ukraine bank, saying it came from loans that were legitimate and have been upheld by the Ukraine courts in multiple decisions.

Several Ukraine legal experts interviewed by the Post-Gazette say, however, that those court decisions were reached during a campaign by the oligarch to file hundreds of cases in search of favorable courts and to withdraw from other courts to avoid losing.

Last year, the Ukrainian government took action when the parliament — at the prodding of the International Monetary Fund — enacted what's known as the "anti-Kolomoisky law" that bans him from ever gaining control over his former bank again.

It's unclear from the new records the total amount of money that moved through the United States, because Mr. Kolomoisky and others shifted funds back and forth between their companies in a dizzying series of transactions.

But the sheer number of transfers — 5,222 in eight years — between companies tied to the oligarch should have prompted Deutsche and other banks to end the transactions, said Paul Pelletier, a former senior federal prosecutor who led the Justice Department's fraud unit. Mr. Pelletier, who once prosecuted money laundering cases in Miami, said:

"You pull the plug. The purpose of due diligence is to do red light, green light — but there was no red light. There were apparently no cops on the beat."The court records, which were released after the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press pushed for them, show the money coursing through the banks as the oligarch and his associates were secretly taking ownership of steel mills and office towers, 22 properties in all.

It's also unclear from the records the purpose of the transactions and whether some of the money was generated from the steel mills when they were operating or from the oligarch's global metals operations.

But prosecutors have identified at least nine of the companies that they claim were used to launder hundreds of millions of dollars, court records show.

Deutsche Bank, which has long maintained a U.S. headquarters in New York, declined to answer questions from the Post-Gazette, saying in an email the bank is not legally allowed to talk about its customers and internal security decisions.

In 2020, the bank acknowledged "past weaknesses" and that it "learnt from its mistakes" and has invested millions to strengthen its internal systems to detect laundering and other crimes. "We are a different bank now," it said.

It was during an explosive court battle six years ago between the oligarch and a former business partner that the layers of Mr. Kolomoisky's operation were stripped back and showed the massive amounts of money pouring into the U.S.

Open critical records

Through an investigation, the ex-partner's lawyers discovered money transfers for hundreds of millions of dollars cascading into the country for companies related to Mr. Kolomoisky — 3,103 transactions by Deutsche alone, court records show.

Deutsche and other banks, along with lawyers for Mr. Kolomoisky, pushed to seal the information, saying it exposed confidential information about the banks' customers.

Not until an effort by the Reporter's Committee for Freedom of the Press and BuzzFeed News to press for data in federal court in the Southern District of New York in 2020 did the judge agree last month to unseal records of the transfer summaries.

Year after year, the money was coming into the country through Deutsche and other banks, with the oligarch the largest recipient of the transactions, totaling $1.25 billion, followed by his fellow Ukrainian billionaire, Gennadiy Bogolyubov — about $900 million — a partner in the U.S. real estate deals.

The records also show $174.5 million moved through Optima Ventures, a company that prosecutors say was used to launder money and buy properties, including an office park in Dallas that was once the headquarters of Mary Kay Cosmetics."The purpose of due diligence is to do red light, green light — but there was no red light. There were apparently no cops on the beat."— Paul Pelletier, former senior federal prosecutor

Another $96.3 million moved through Optima Acquisitions, a company that prosecutors say was used to clean money and buy steel mills.

Former employees who worked at the Ohio steel factory say they're surprised at the amount of money flowing into the U.S. because of the difficulties they faced in getting basic parts and bills paid on time.

Just after the shutdown of the factory in 2016, money was owed to the gas and electric companies and the federal government for a fine that had been imposed for workplace safety violations. Factory general manager John Scheel wrote in an email to company executives:

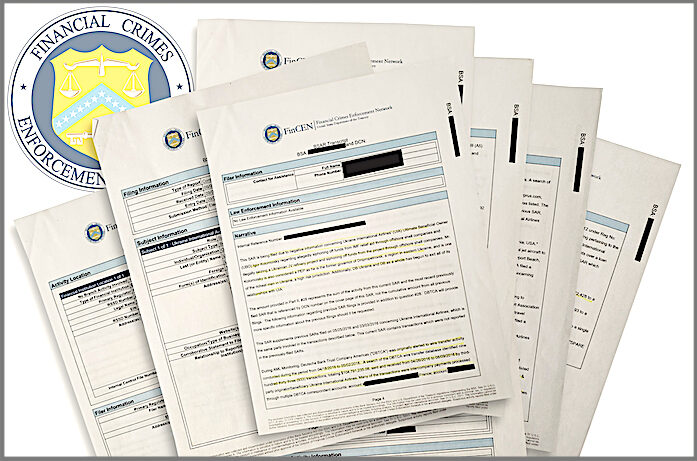

"We have not paid for our copy machines which are about to be repossessed. We have not paid for our phones, which are our only mode of communication with the plant. We have not paid for the liability insurance for Warren Steel Holdings. We have not paid the quarterly installment for our OSHA fine that we negotiated."After years of transferring money into the country for the oligarch, Deutsche Bank filed at least three suspicious activity reports in 2016, finding patterns that raised alerts about incoming funds for one of his aviation companies.

The bank noted in one of the reports that Mr. Kolomoisky was a former Ukraine provincial governor who was suspected of widespread fraud in his country — charges he has denied. The bank's fraud experts also questioned the legitimacy of millions in payments between companies with no known purpose for the transactions.

The reports, shared with the Post-Gazette by BuzzFeed News, show the bank started to cut its ties with the company, but not before it moved about $215 million that year. Mr. Cardamone of Global

Financial Integrity said the move came too late. "That's bolting the door behind the horse," he said.

While the U.S. government's case against the oligarch and his partners has gained wide publicity, the role of Deutsche in moving the money remains one of the least known elements of the entire operation, said experts interviewed by the Post-Gazette.

As a correspondent bank taking in money from overseas, Deutsche was a gateway.

Thomas Nollner, a former regulator for the Comptroller of the Currency stated:

"They could not have used the U.S. banking system [without Deutsche]. The bank should have done its due diligence. He's high risk. He's a politically exposed person. This should not have gotten by someone's scrutiny."Mr. Kolomoisky was a lightning rod of controversy in Ukraine at the time, especially after he dispatched his own armed militia into a government oil company in 2015 during a dispute.

Tim Ryan, a Democratic U.S. House member whose district includes the shuttered Ohio steel factory, said in an interview last year that any analysis of the case and the damage that it caused needs to include the pivotal role of the bank.

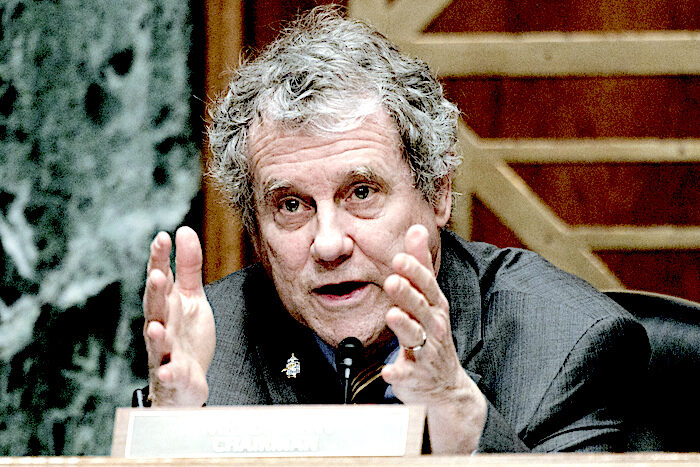

"Especially in this case, we need to see if they met their responsibilities. ... We need to know if they did — or they didn't."A spokesperson for U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, who chairs the Senate Banking Committee, said that Deutsche Bank has had a long history of regulatory violations but declined to discuss any potential inquiries by Congress.

"It's low-hanging fruit. It's a lot of money. Shouldn't we have a system that reacts quicker to that kind of money? The burden is to show that the money is [suspicious]. What did it show? It doesn't look like anyone was doing heightened due diligence."Mr. Kolomoisky is considered a politically exposed person and the money was arriving from offshore, it required the bank to perform an even higher level of due diligence.

He said what also distinguishes the case from other laundering investigations is that the money didn't go to the familiar havens of Miami and New York. It went to steel factories in small towns.

"It harmed real hard-working Americans in Middle America," he said.

Reader Comments