"[T]he Neolithic is a gradual and slow process, and in particular in the Danube Gorges region we know that the transition was long and determined a mixing of two cultures and peoples (farmers and foragers)," senior author Emanuela Cristiani and first author Claudio Ottoni, researchers at Sapienza University of Rome's diet and ancient technology laboratory, explained in an email.

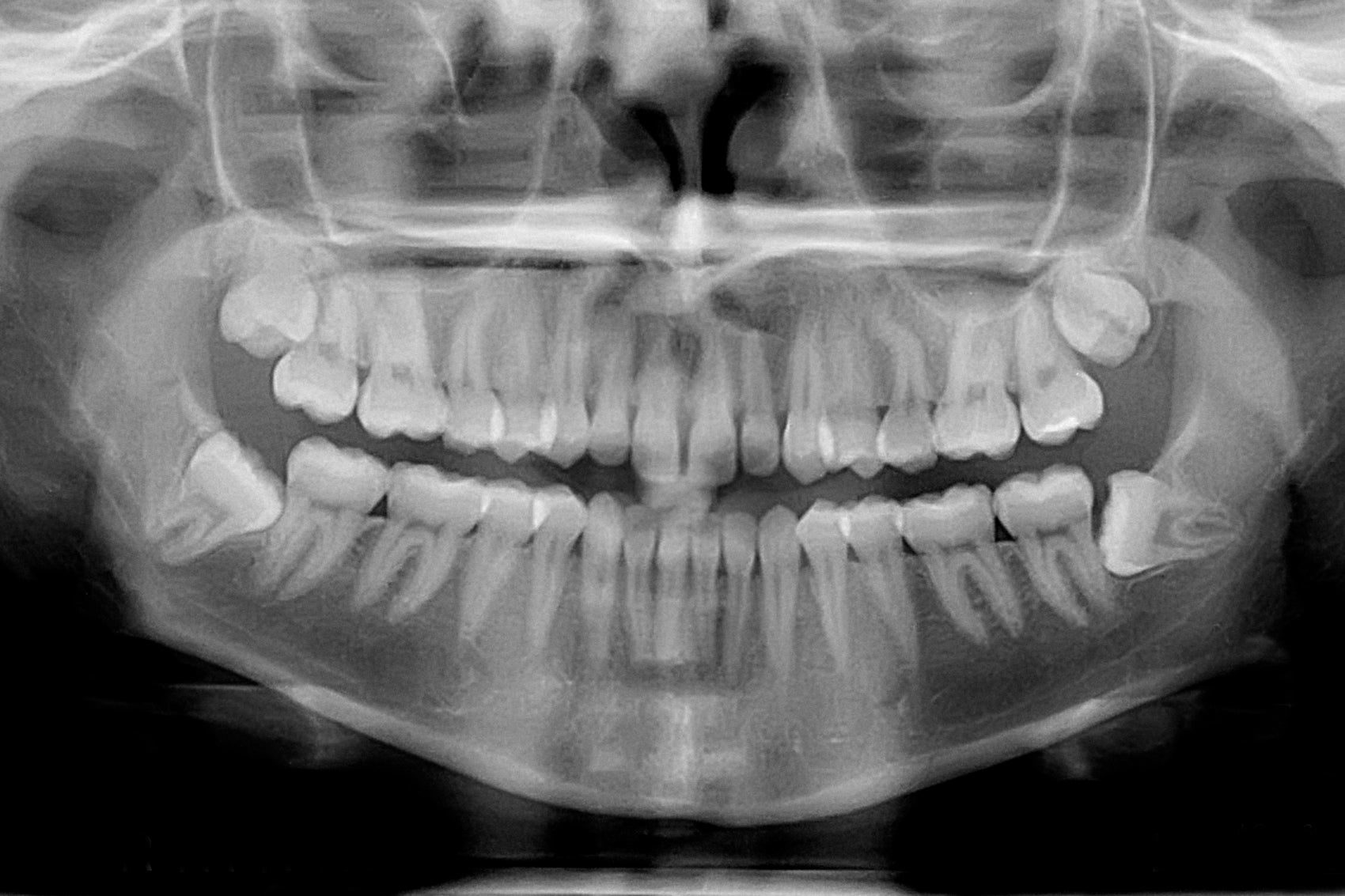

Their team from Italy, the US, and Austria conducted metagenomic sequencing on dental calculus samples from 44 representatives of ancient farming or foraging populations found in the Balkans or the Italian Peninsula between the Paleolithic period and the Middle Ages. The analysis, scheduled to appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, revealed microbial representatives that became more common with the introduction of agriculture despite relatively stable overall oral microbial communities.

The investigators also detected versions of a microbe known as oral taxon 439 from the Anaerolineaceae family that was common across oral microbial communities but varied from one location to the next. During the transition from foraging to farming, their results suggested, an oral taxon 439 lineage that was linked to ancient human populations in the Near East appeared to outperform a variant of the bug that had been found in foraging populations prior to the arrival of Neolithic farmers.

"We demonstrate that the genome of an oral bacteri[um] diversified geographically and recorded one of the most dramatic changes in our biological and cultural history, the spread of farming," the authors wrote, noting that "transition to agriculture did not alter significantly the oral microbiome of ancient humans, whereas more significant changes occurred later in history, including the development of peculiar antibiotic resistance pathways."

Following up on prior studies demonstrating oral microbiome differences between present-day populations and their apparent ties to health and disease, along with ancient analyses focused on more recent times in history, the team dug into samples going back to the Upper Paleolithic to characterize the oral microbial communities found in foragers as they interacted with early farming populations in Southern Europe.

"Archeological dental calculus, or mineralized plaque, is a key tool to track the evolution of oral microbiota across time in response to processes that impacted our culture and biology, such as the rise of farming during the Neolithic," the authors explained, adding that "the extent to which the human oral flora changed from prehistory until present has remained elusive due to the scarcity of data on the microbiomes of prehistoric humans."

With shotgun metagenomic sequencing on the mineralized plaque samples from 28 ancient individuals from the Danube Gorges region of Romania and Croatia, 10 central Italian representatives, and half a dozen ancient individuals from northwestern Italy, the researchers retraced oral microbiome features in foragers and farmers across the Late Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Early Neolithic, Bronze Age, and medieval periods.

"By documenting the taxonomic composition and functional activity of the human oral microbiota in a large number of samples prior to and after the adoption of agriculture," the authors wrote, "we tested whether the transition to farming that started with the Neolithic changed the human oral microbiome in the Balkans and Italy."

The team's analyses, which included data on ancient and modern oral microbiomes described in humans and chimpanzees in the past, pointed to the presence of ancient oral microbiome clusters that were largely distinct from those found in present-day human populations.

While the oral microbial communities were similar in individuals from foraging populations in the Late Mesolithic and farming groups dated to the Neolithic, the researchers reported, there was an uptick in microbes from oral taxon 807 from the Olsenella genus in the oral microbiomes from Neolithic farmers. On the other hand, the Streptococcus sanguinis species tended to be more common in the mouths of Mesolithic foragers.

There were also subtle differences in the species detected in oral microbiomes from foragers in Italy compared to those in the Balkans. In contrast, the team saw relatively uniform microbial communities in the ancient calculus samples from farming individuals from different sites.

Along with differences in representation of Anaerolineaceae bacterium oral taxon 439, Olsenella oral taxon 807, and other microbes, the study revealed functional shifts between the ancient samples and those found in more modern human mouths, reflecting significant oral microbiome changes in relatively recent history that exceeded those found during the forager-to-farming transition in the Balkans and Italy.

"Our findings ... illustrate that major taxonomic shifts in human oral microbiome composition occurred after the Neolithic," the authors wrote, "and that the functional profile of modern humans evolved in recent times to develop peculiar mechanisms of antibiotic resistance that were previously absent."

"The fact that we see more significant changes with present-day humans is not totally unexpected given the massive adoption of antibiotics since the last century, which may have driven significant changes in the oral microbial composition," Cristiani and Ottoni added.

Comment: See also: