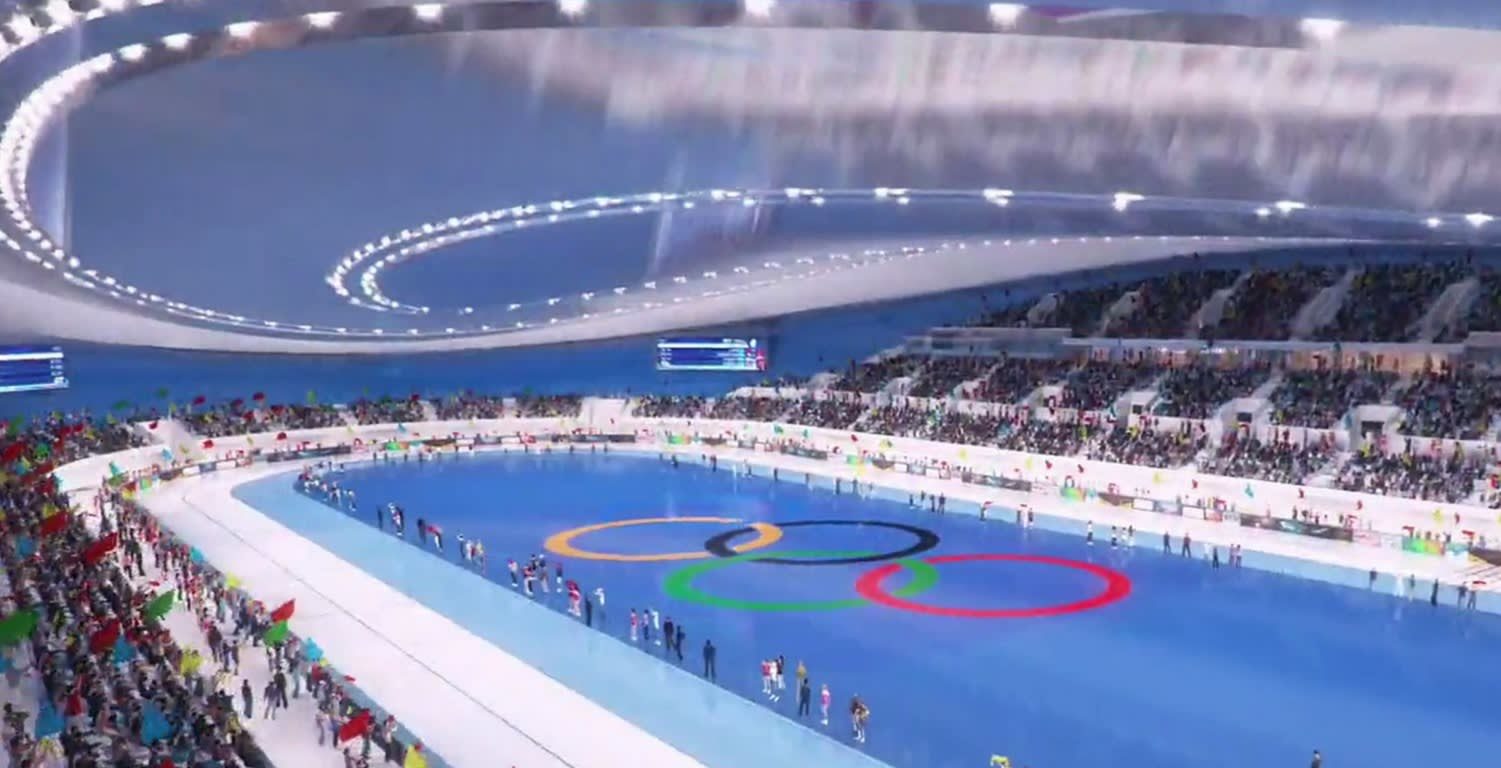

© International Olympic CommitteeAn ice rink for the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.

China seeks to have its planned sovereign digital currency ready in time for the 2022 Winter Olympics here, the central bank revealed Tuesday, as the coronavirus pandemic accelerates a shift away from cash.

The government plans to run pilot tests at Olympic venues, though there remains no official timetable for a release, People's Bank of China Gov. Yi Gang told Chinese media in an interview released by the central bank. Limited trials are underway in Shenzhen, Suzhou, Chengdu and the Xiongan New Area in the northern province of Hebei, he said.

If the government is satisfied with the results of this year's tests, the currency "will be issued next year," said a member of the State Council, China's cabinet, with knowledge of the project. "If it's not satisfied, more tests will be conducted next year."

The coronavirus has made consumers wary of physical cash that could carry pathogens, and digital-currency platforms are poised to benefit. It has become easier to use and popularize new payment technologies, said Eddie Yue, chief executive of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the territory's de facto central bank, in April.

The digital yuan is linked to the holder's smartphone number, with transactions taking place through an app. Apparent screenshots of the program that circulated online in April show a resemblance to

Alibaba Group Holding's popular Alipay platform, including the use of bar codes and QR codes to make payments.

The digital-yuan app would have a function Alipay lacks: Users can transfer money between accounts by tapping phones, much like having physical cash change hands. The currency will be legal tender, so it can be exchanged without needing a bank as an intermediary.

This may help make China's economic system more resilient.

Cash is used much less often in China than elsewhere thanks to the widespread adoption of services like Alipay and

Tencent Holdings' WeChat Pay,

meaning that the economy could be all but paralyzed if a disaster disrupts mobile phone service. By enabling transfers with no need for an internet connection, the digital-yuan app would ensure that commerce can continue as long as power is available.Using digital instead of physical currency would entail privacy trade-offs. Mu Changchun, a PBOC official overseeing the central bank's digital-currency research, said in November that

the size of transactions would be limited based on identity verification.A phone number alone would permit only small transactions, while providing proof of identity or a photo of a debit card would raise the limit. Speaking with a bank representative in person could allow for the cap to be removed entirely.

Suspected criminal activity will be uncovered via transaction histories.

Artificial intelligence could flag payments as possible illegal gambling, for example, if they take place late at night, start at the 10 yuan ($1.40) minimum, and gradually increase in size before abruptly halting, Mu said.

The digital yuan could have unintended consequences for the overall financial system. Digital currency, being a liability on the central bank's balance sheet, is safer than normal bank deposits. The HKMA's Yue warned that in a crisis, depositors could withdraw cash from banks and exchange it for digital yuan. In a country that saw runs on regional banks

just last year, this is a risk that cannot be ignored.

There could be competitive implications as well. The app will compete directly with Alipay and WeChat Pay -- but with the difference that

stores will be legally required to accept it given the digital yuan's status as legal tender, granting it an advantage over private-sector rivals.

Comment: Looks like the fake pandemic is paving the way for long desired controls over how people spend their money or if they can spend their money at all.