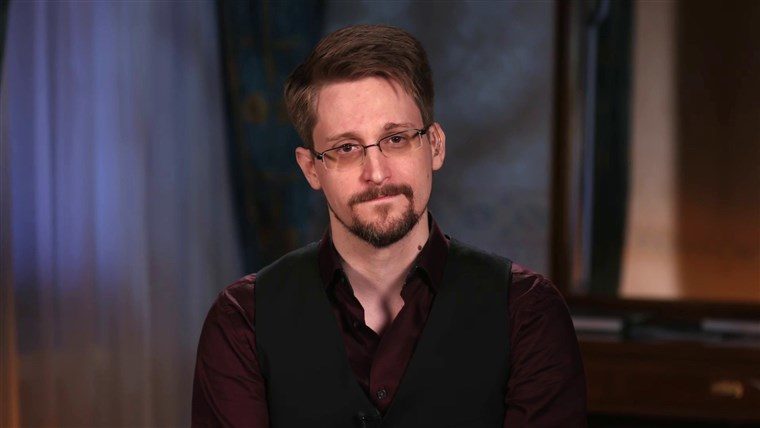

© MSNBCEdward Snowden in Moscow speaking with Brian Williams on Sept. 16, 2019.

Edward Snowden, the former intelligence contractor whose disclosures about highly secret U.S. surveillance programs rocked the nation's espionage agencies, must pay the federal government

proceeds from his new book because he failed to first get approval for that book's contents as required by employment contracts, a judge has ruled.

The decision by Judge Liam O'Grady in U.S. District Court in Eastern Virginia did not detail how much Snowden should have to pay the U.S. government in connection

with his book "Permanent Record."That amount likely will be decided later by O'Grady.

The judge's ruling Tuesday

came in response to a request by the government to grant summary judgment in a lawsuit against Snowden for violating the terms of secrecy agreements he signed while working at the Central Intelligence Agency as an employee and contractor, and at the National Security Agency as a contractor.

The Justice Department is seeking to recover "all proceeds earned by Snowden," it has previously said.In a tweet on Thursday, Snowden wrote, "The government may steal a dollar, but it cannot erase the idea that earned it.""I wrote this book,

Permanent Record, for you, and I hope the government's ruthless desperation to prevent its publication only inspires you read it — and then gift it to another."

Snowden, now in Russia, remains a fugitive from prosecution on federal criminal charges for alleged violations of the Espionage Act

relating to his exposure in 2013 of details of the NSA's massive collection of phone and internet data about Americans.Snowden's disclosures

led Congress to ban the bulk collection of Americans' phone records.

O'Grady's ruling noted that all three agreements Snowden signed required him to protect information and material of which he had knowledge from unauthorized disclosure.

They also required him to submit for review any writings or other presentations he prepared which related to intelligence data or protected information.

Snowden's book, which was published in September in the United States by Macmillan Publishing Group, details CIA and NSA intelligence-gathering activities, including classified programs.

Snowden did not get clearance from either agency for the book. Nor did he get clearance for intelligence-related materials he displayed during talks he gave for various public events, which included at least one slide "marked classified at the Top Secret level," the ruling said.

In his defense of the lawsuit, Snowden argued that the government had breached the secrecy agreements "by indicating it would refuse to review Snowden's materials in good faith and within a reasonable time," O'Grady noted in his ruling.

Snowden also argued that the suit "is based on animus toward his viewpoint," and that

the government only selectively enforced secrecy agreements, the judge said. And finally, Snowden maintained that the agreements did not support the government's claim against him.

But in his ruling, O'Grady said "the contracts at issue here" — the secrecy agreements — "are unambiguous and clear."And the judge said there is "no genuine dispute" that Snowden breached the agreements.A spokeswoman for the U.S. Justice Department did not immediately respond to requests for comment by CNBC about O'Grady's ruling.

Brett Max Kaufman, a lawyer on Snowden's legal team, said, "It's farfetched to believe that the government would have reviewed Mr. Snowden's book or anything else he submitted in good faith.""For that reason, Mr. Snowden preferred to risk his future royalties than to subject his experiences to improper government censorship," said Kaufman, who is an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union's Center for Democracy.

"We disagree with the court's decision and will review our options, but it's more clear than ever that the unfair and opaque prepublication review system affecting millions of former government employees needs major reforms."

In April, the ACLU and the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University

filed a lawsuit on behalf of five former public servants challenging the prepublication review system that affects former intelligence-agency employees such as Snowden and military personnel.

The suit argues that the system violates the Constitution's First and Fifth Amendments.

The case was filed for former employees of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, a former CIA employee, a former Marine, and an ex-employee of the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter