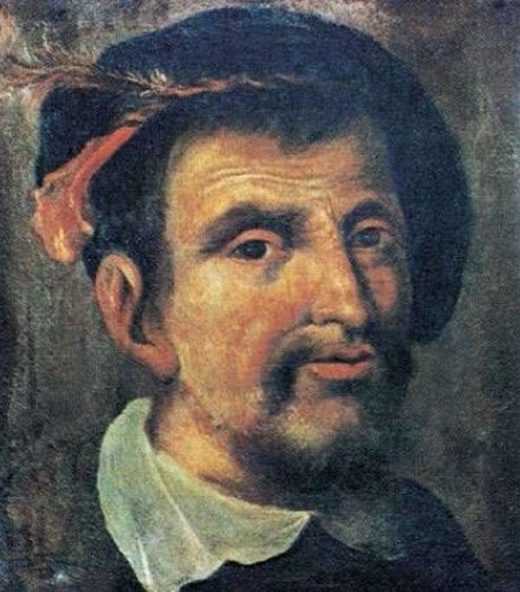

While Columbus was exploring the oceans and pursuing a quest to find the New World, his son was avidly trying to read every book he could lay hands on. In fact, he aimed "to create a universal library 'containing all books, in all languages and on all subjects, that can be found both within Christendom and without'," according to the Guardian.

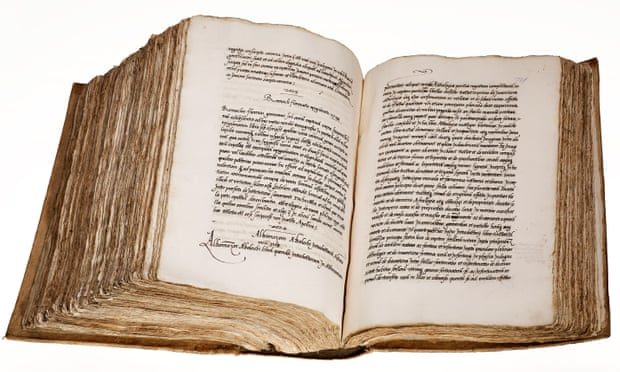

For his zealous effort, Colón even hired a fleet of scholars to go through the books he owned, asking them to produce quick summaries for what would be a ground-breaking 16-volume manuscript with cross-references to other items in the library collection. He would personally proofread and edit each of those summaries before submitting them to the manuscript.

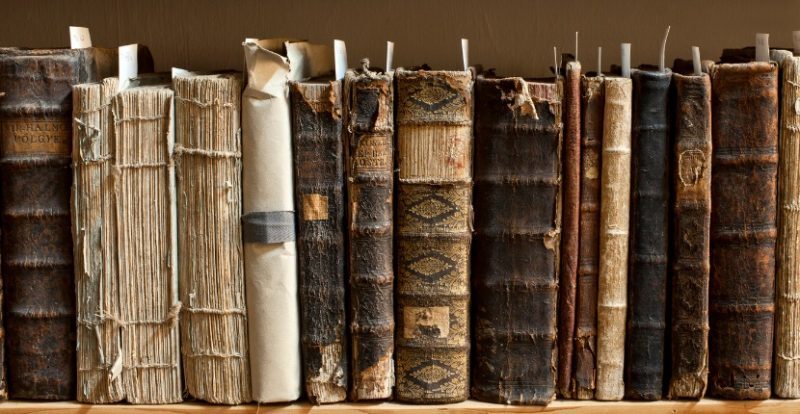

For centuries, The Book of Epitomes was considered lost, until it was recently identified as part of the Arnamagnæan Collection at the University of Copenhagen, the Guardian reports. The summaries fill over 2,000 pages and a great deal of them refer to books that have been entirely lost to history. For shorter volumes, the scribes added one-pagers; for books such as those of the great Greek philosophers more extensive abstracts taking up dozens of pages were added.

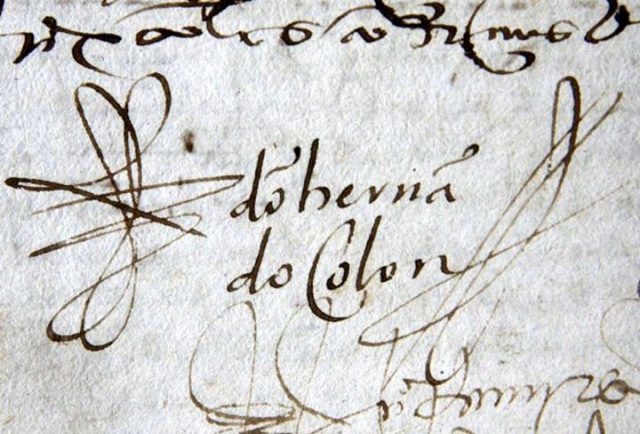

The manuscript was, in fact, one of four means of navigating through Colón's library. According to The Arnamagnæan Institute, Colón had "four types of inventories to keep track of his books," included "a list of authors, a list of sciences (that is, subjects), a list of materials (that is, themes of keywords) and finally a list of epitomes." Each of these "could be cross-referenced through numbers assigned to the books in each of the lists."

Colón tirelessly added to the book collection until his death in 1539. It's estimated that the library comprised around 15,000 volumes; sadly, only a quarter of these are known to have survived. After his death, Colón's collection was relocated to Seville Cathedral, where negligence led to the loss of much of the library.

Cambridge-based scholar Dr. Edward Wilson-Lee, author of a recently published biography of Hernando Colón titled The Catalogue of Shipwrecked Books, has said The Book of Epitomes is like a window into a "lost world of 16th century books," reports the Guardian.

"It's a discovery of immense importance, not only because it contains so much information about how people read 500 years ago, but also, because it contains summaries of books that no longer exist, lost in every other form than these summaries," he said.

The collection in which The Book of Epitomes has now resurfaced is ascribed to Icelandic-Danish scholar and collector Árni Magnússon, who lived from 1663 until 1730.

Upon his death, Magnússon gifted his personal book collection to the University of Copenhagen. The great majority of his 3,000 volumes donation is in Icelandic and other Nordic languages. Only about 20 items are in Spanish, including The Book of Epitomes, and the language barrier was likely a reason why hardly anyone paid attention to it over the last few centuries.

The information eventually reached Colón's biographer, Wilson-Lee, and co-author María Pérez Fernández. In collaboration with the Arnamagnæan Institute, Wilson-Lee and Fernández are due to work on digitizing the long lost manuscript.

It's surprising that The Book of Epitomes reappeared in a country so far north, and how, in the first place, a copy of it came to be a possession of Árni Magnússon. One possibility is that it journeyed with a bunch of other manuscripts, from Seville to Copenhagen, through diplomatic channels.

If Colón had someone to look up to for such an aspiration, it was definitely his explorer-father, who was confident enough to believe Spain would one day reign over the entire known world.

Colón himself traveled a lot, sometimes even accompanying his father. He also authored one of the earliest biographies on Columbus. "Between 1509 and his death in 1539, Colón traveled all over Europe - in 1530 alone he visited Rome, Bologna, Modena, Parma, Turin, Milan, Venice, Padua, Innsbruck, Augsburg, Constance, Basle, Fribourg, Cologne, Maastricht, Antwerp, Paris, Poitiers and Burgos," notes the Guardian.

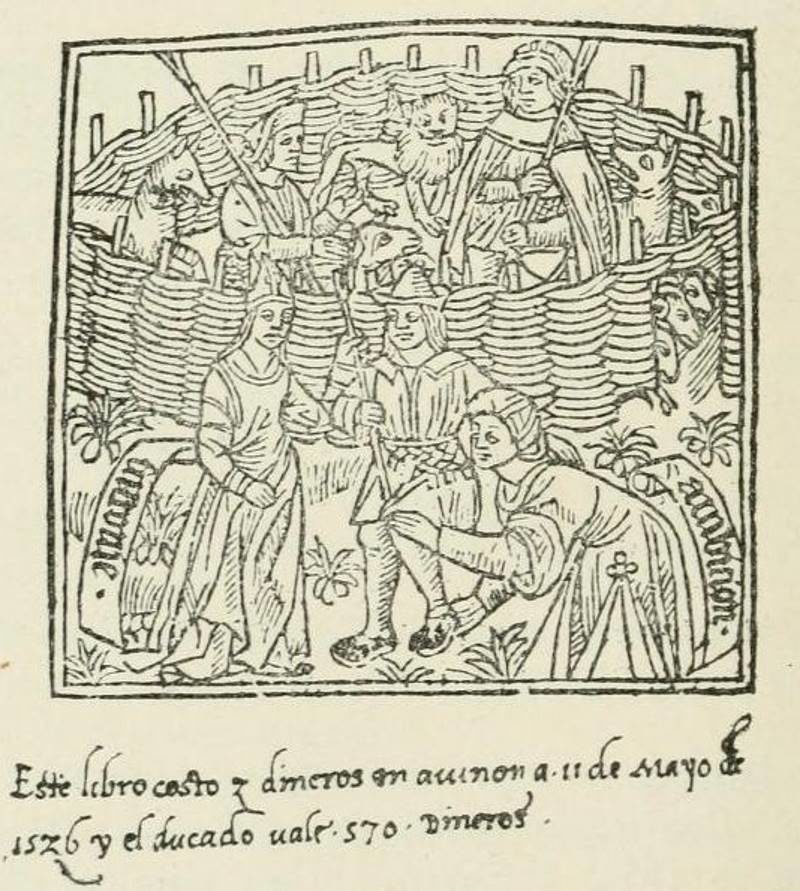

The purpose of his extensive traveling time was again to collect books and any other printed material, for example, tavern posters or news pamphlets. At the time, his mass of books was called Biblioteca Hernandina and it grew to be at least three times the size of other private library collections of the era.

Colón also had some intriguing reading habits. On each book, he noted where and at what cost the copy was purchased - in what currency the exchange rate that day. He was also keen to note where he was reading the book and his thoughts as he moved through the pages. Colón also kept to strict protocols of organizing his collection of books, so the production of The Book of Epitomes should come as no surprise.

At the time the biggest private library in Europe, today Biblioteca Hernandina is called Biblioteca Colombina. The collection has shrunk to as few as 4,000 titles. While it was stored at Seville Cathedral, some of the copies are said to have been stolen; others were damaged in incidents such as flooding.

Beyond the loss of books, the remnants of Colon's great project are here with us, and his character teaches a fantastic story about a man who was resolute to gather all the books out there. If not read them all, at least have a brief idea of what they were all about. Unknowingly, Colón was reinventing the very idea of knowledge.

Stefan Andrews is a freelance writer and a regular contributor to The Vintage News. He is a graduate in Literature. He also runs a blog - This City Knows.

Reader Comments