Moses would never make the trip to the Promised Land, the Bible tells us, but he was buried on that very mountain ridge. Thousands of years later, apparently sometime between 350 and 380 C.E., early Christians built a church and monastery on the mount where the patriarch was supposed to have gazed westward. And pilgrims began to arrive.

The question is who exactly those pilgrims visiting between the third and eighth centuries were. Where did they come from? What were they like?

It's hard to know because early Christian monasticism prized the collective over the individual. Even secondary burials (when the body was left to decay for a year or two, at which time the bones would be collected and put in a stone or clay vessel) were "communal" at Mount Nebo, negating these people's individuality to the last. "The skeletal remains were commingled," write Margaret Judd of the University of Pittsburgh, and Lesley Gregoricka and Debra Foran of Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario in the journal of Antiquity.

Yet despite this deliberate effort to downplay the pilgrims' identities, origins and ethnicities, the team overcame. Mosaics dedicated to the monks around 1,500 years ago and isotopic analysis of teeth revealed that nearly half the pilgrims buried at Mount Nebo had come from somewhere else.

The conclusion from that and other evidence, including skeletal demographics, is that early Christian pilgrims came to Mount Nebo from far and wide. "Mount Nebo was cosmopolitan, attracting non-local pilgrims and monastics alike, due in part to the site's association with the Prophet Moses," the team writes.

A church with a view

No archaeological evidence has ever been found to back the biblical tale of Moses, the Exodus from Egypt, or the mass migration of early Hebrews to the fertile land of Canaan. (And no, there's no evidence that Mount Sinai is in Saudi Arabia, another ages-old theory recently bruited about. Again.) It's true that the late Prof. Adam Zertal proposed that mysterious stone walls found at Khirbet el-Mastarah, in the wasteland of the Jordan Valley, are the remains of camps erected by the ancient Israelites crossing, very, very slowly, into Canaan. The main grounds for his theory are that the stone ruins date to about 3,200 years ago, putatively the time of the historic migration. Prof. David Ben-Shlomo of Ariel University later postulated that the nomadic ancients built stone shelters for their livestock, while the people themselves lived in tents.

That's the beginning and end of possible archaeological backing for the Moses story, so far.

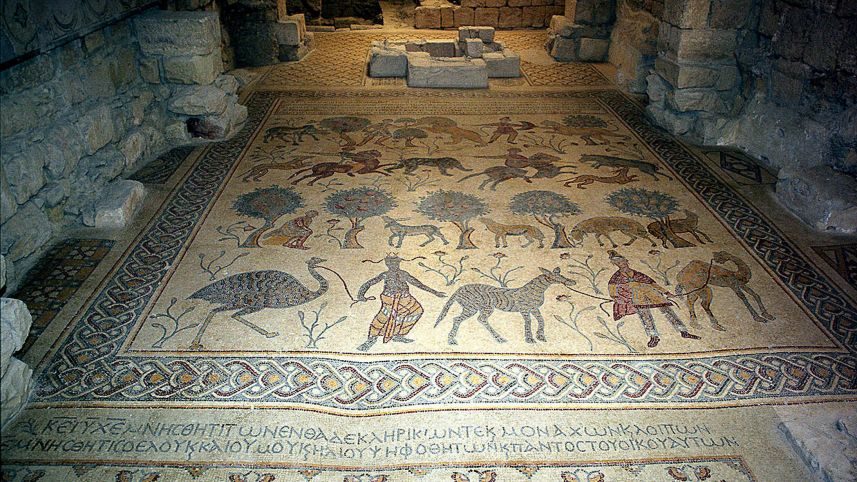

Thus the early Byzantine church constructed on Mount Nebo in the second half of the fourth century was positioned on the basis of local tradition regarding the place where Moses stood and died, nothing more. Yet it proved magnetic for early pilgrims, becoming a center of a network of monasteries in central Transjordan during the Byzantine period, the researchers say.

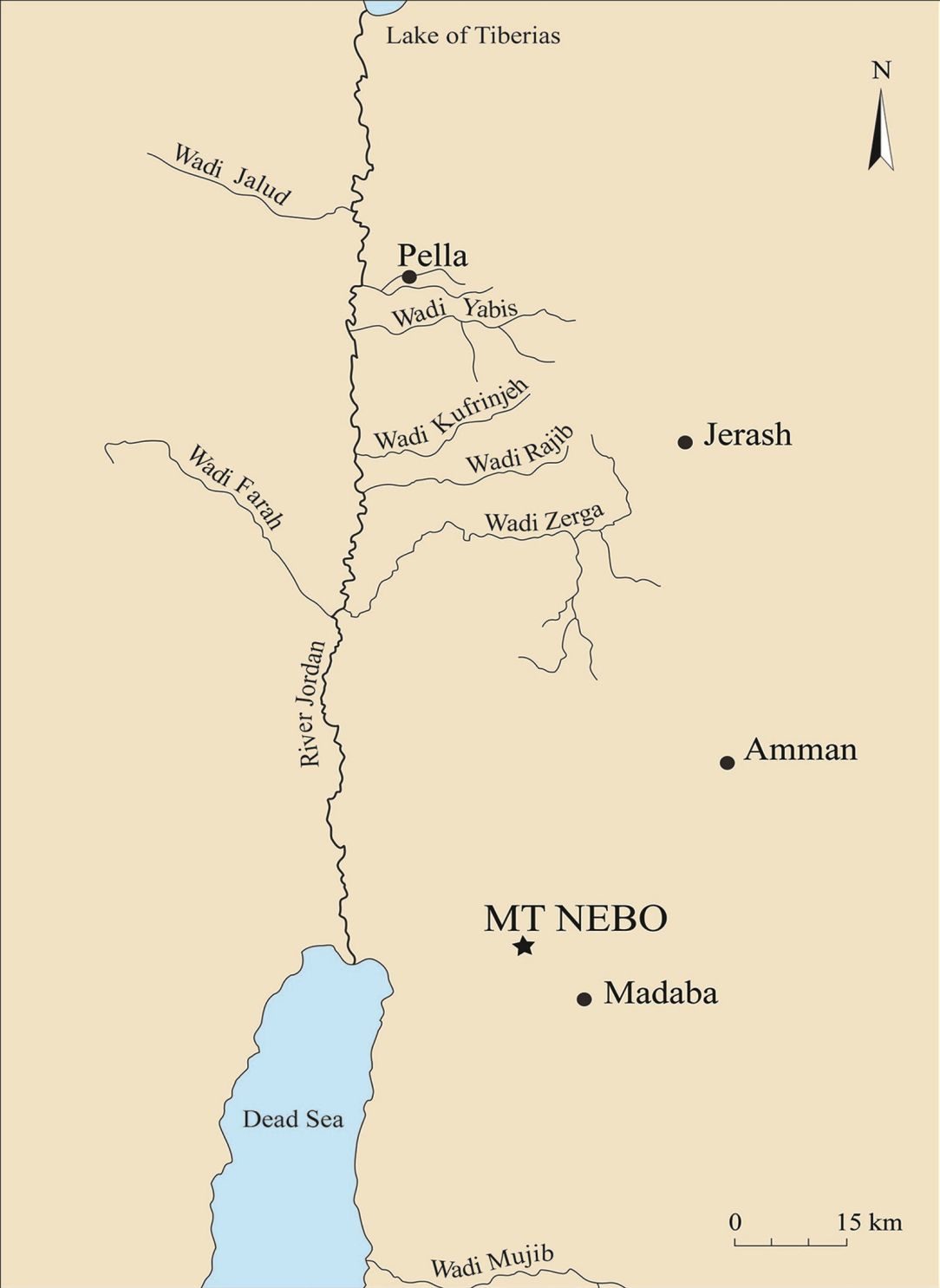

Mount Nebo lies just outside Madaba, the Jordanian town that houses St. George's Church, dated to the sixth century, which in turn houses the famed earliest-known map of the Holy Land and its pilgrimage sites. That map, on the church floor, is dated to about the year 560. Madaba is at the crossroads of ancient routes for trading - and for pilgrimages.

Later visitors, including theologian Peter the Iberian and the so-called Piacenza Pilgrim, also wrote of Mount Nebo, describing a towering church surrounded by monasteries. In the late sixth century, a chapel was dedicated to the community leader Robebus, we know from the mosaic announcing the dedication.

From the sixth century, the historical record went silent. In 1217 the German pilgrim Thietmar visited and mentioned the place. That was it, the team says.

Comment: The evidence shows there's a good reason it went quiet: 536 AD: Plague, famine, drought, cold, and a mysterious fog that lasted 18 months

Rodents help out

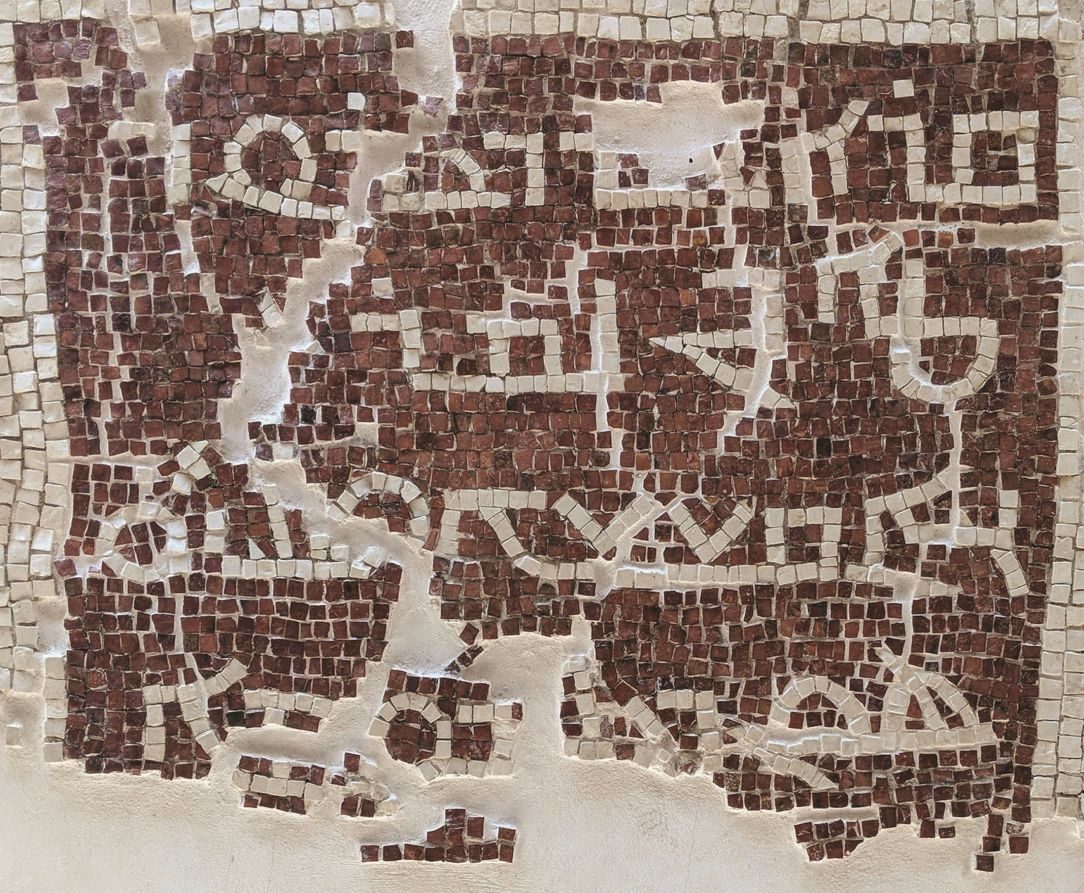

While the Christian structures at Mount Nebo have been explored by archaeologists since the 1930s, the commingled skeletal remains were only uncovered this millennium, from two chambers in the eastern crypt. The bones were dated to between around 400 and 530, between the time of Egeria's visit and Robebus' rule. Support for the time line is provided by Roman coins found in the crypt.

Regarding the origin of the long-dead people, different geographical regions have different proportions of certain isotopes. Interestingly enough, the controls "to estimate local isotope bioavailability" included eight local rodents.

The results were enlightening. Analysis of strontium and oxygen isotopes in tooth enamel revealed that about half the people had grown up far away - their isotopic signatures weren't typical of the locals. They would have come to Mount Nebo later in life.

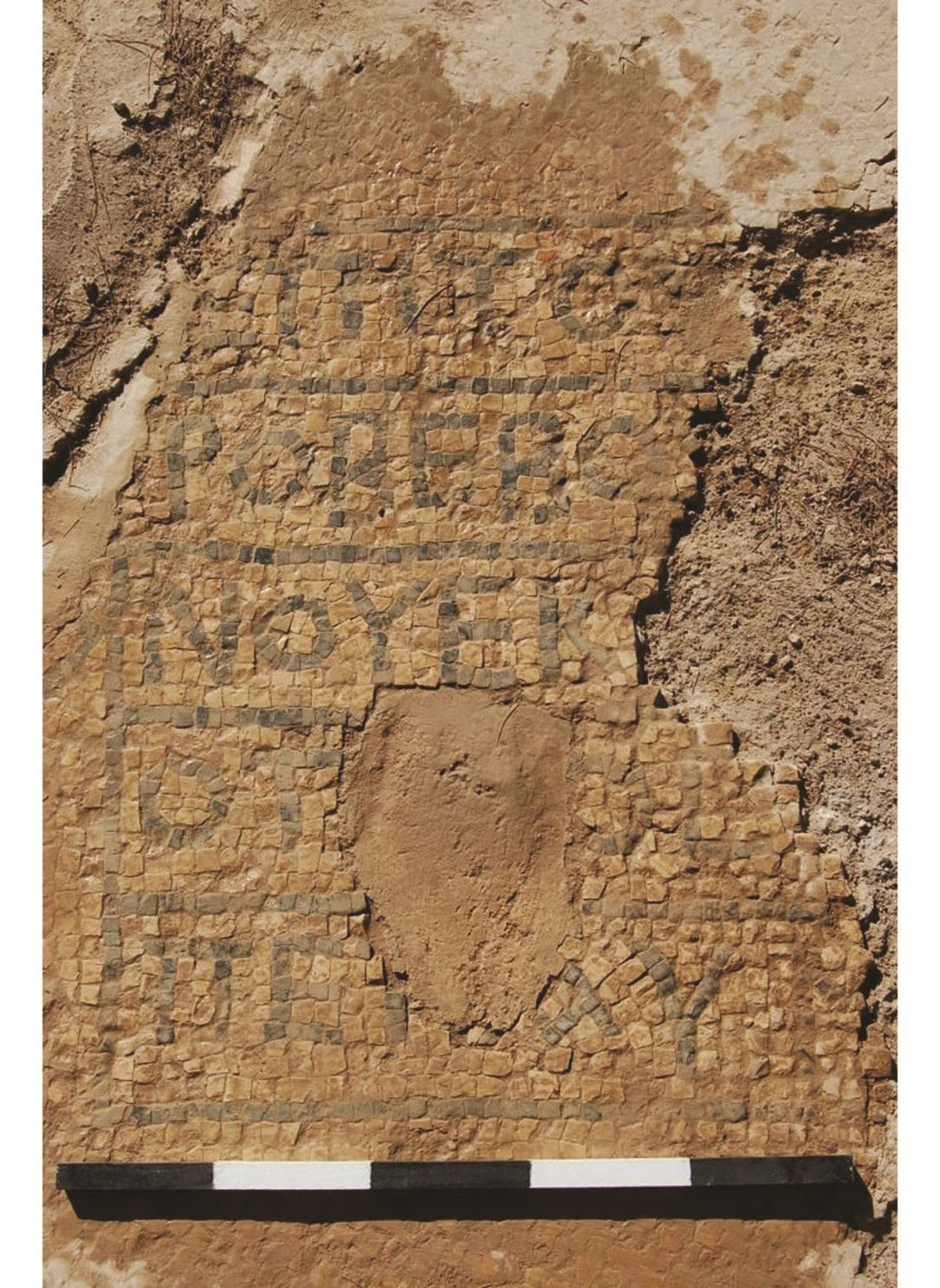

In Uyun Musa, an oasis in Jordan not far from Madaba, where Moses is thought to have halted and bashed a rock with his walking stick to summon water, is a church called Kaianus. In the church is a mosaic dating to the late fifth century or early sixth. On the mosaic is a name: Gayyan.

The ancients weren't obsessed with historical accuracy or precise names, and the name Gayyan is very similar to Gaianus.

Gaianus is name of the bishop of Madaba, according to Cyril of Scythopolis, a sixth-century monk. It's also the name of a man who, Cyril wrote, lived in Malatya in central Turkey.

Other names also provide clues to the diverse origin of the faithful at Mount Nebo. True, the Christians were supposed to forgo their personal vanities, but there were 44 dedicatory mosaics. Of the names, the team says, 39 percent were Semitic, such as Kasiseus; 48 percent were Greek, such as John; and 7 percent were Latin, such as Longinus.

The finds also suggest that Lady Egeria may have been a little lonely in her pilgrimage. Among the dozens of people buried at Mount Nebo who are now being studied, none are thought to be female - though there's a debate about one skeleton. A comparison with 11 other monastic sites in the region shows that almost all human remains were male, though the remains of one woman was found at Deir Ein Abata in Jordan.

Pilgrims spoke only of males at Mount Nebo, the team points out; female monastics lived elsewhere. But it's also true that in the Late Antique period, sometimes women would pass as men in order to join religious communities, and some would only be found out at death. That one ambiguous skeleton at Mount Nebo could have been a woman disguised as a man to better serve the Lord, as she saw it.

To this day, people throng Mount Nebo, possibly following in the footsteps of Moses, or not. We'll never know. And they still come from far and wide. And when they stand on the summit, they can see the fertile land of Israel - and Jerusalem, on a good day.

Comment: There's evidence that there were connections even further afield and earlier than that stated above: Beads found in Nordic grave reveal trade connections with Egypt 3,400 years ago

See also:

- Celestial Intentions: Comets and the Horns of Moses

- Judaism and Christianity - Two Thousand Years of Lies - 60 Years of State Terrorism

- Ancient DNA sets the record straight on the Canaanites

- History textbooks contain 700 years of false, fictional and fabricated narratives

- Senior Israeli archaeologist casts doubt on Jewish heritage of Jerusalem

- UK - Israel hides colonization policy with fake archaeological digs

And check out SOTT radio's: