© Miss Open

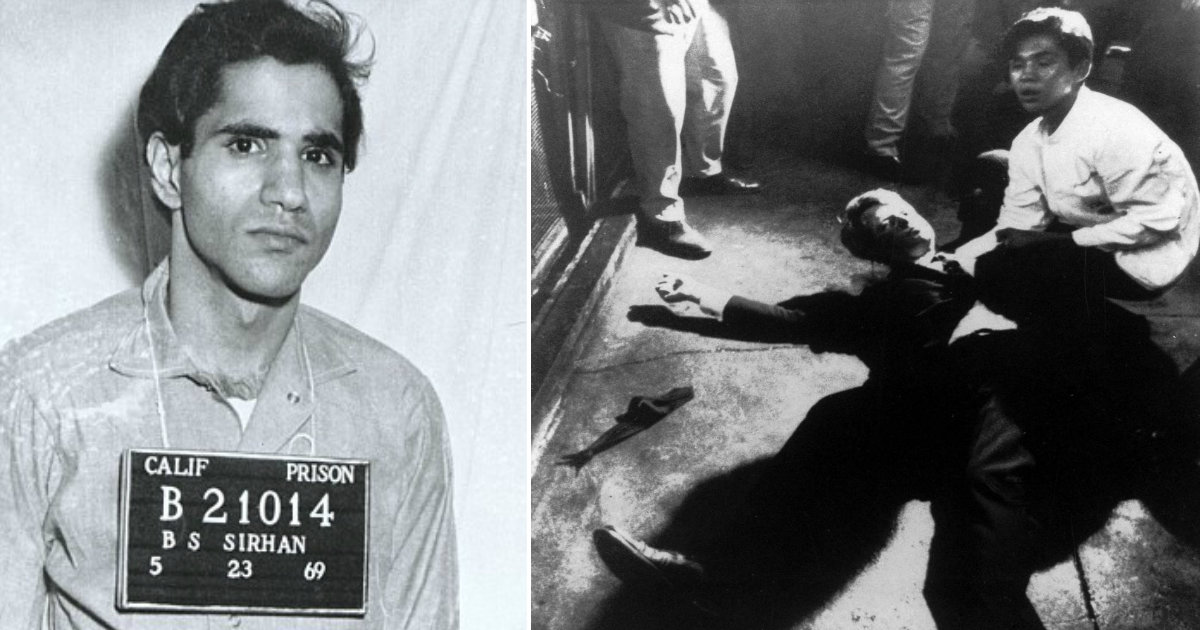

The assassination of Democratic Party candidate Robert F. Kennedy in Los Angeles the night he won the California presidential primary in June 1968 dealt a shocking blow to the national consciousness.

After all, the murder came less than five years after the shooting death of his brother, President John F. Kennedy, and the official investigations into both deaths would prove to be highly controversial, creating generations of conspiracy theorists eager to explore whether there were mysterious forces behind the two deaths.

Lifelong information activist and researcher Lisa Pease has immersed herself in the case of RFK since 1992, when she stumbled across extensive Los Angeles Police Department case files on the assassination when she opened the wrong drawer at the Los Angeles Public Library's main downtown branch. Delving into the files and conducting countless interviews ever since, she has crafted the massive 512-page new book

A Lie Too Big to Fail: The Real History of the Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, which pokes many holes in the official story that former Pasadena resident Sirhan Sirhan was his killer.

"I was looking for microfilm on the JFK shooting, when I opened the drawer holding the LAPD files on RFK," Pease recalls. "I was like, 'Wow, how many people have been through this?' There were only four or five books on the case, saying a lot of the same things as the official story about Sirhan doing it.

"

But these files showed that another guy had been apprehended at the hotel and handcuffed, and I had never heard of that," she adds. "In my book I show that there were

six different suspects discussed on police radios right after, who were quite different in age, size and weight.

Witnesses reported men running from the scene with guns, or who were behaving so suspiciously they drew their attention. But on the police radio transcripts, the cops were quickly told to stop talking about it and soon we only had Sirhan accused."

Pease has had a long and varied career, mixing work as a computer programmer and an instructor with stints on the paid staff of two different presidential campaigns and occasionally acting. She was also a key player in a 1990s-era magazine called

Probe, which investigated the JFK assassination and other murky incidents in modern American history via documents that were declassified by the Assassination Records Review Board.

When

Probe ultimately closed up shop, the specialty publishing company Feral House published an anthology of its top essays called

The Assassinations. As a result, Pease teamed up with Feral House to release her new book. She had also been impressed by the fact that

Feral had come out on top when the CIA tried to sue them. "This whole case on RFK is fascinating and highly disturbing to me," she says. "I felt a responsibility to Sirhan when I realized how innocent he truly was.

Everyone assumed he shot actual bullets and shot some people there, if not Kennedy. But the details I have was that

he was shooting blanks and didn't know what he was a part of, because he had been programmed to do things. You can't be hypnotized to do something against your will, but you can be hypnotized to act against your knowledge."

In addition to extensively examining the LAPD files, Pease spoke with dozens of key figures from the night of the assassination and its subsequent investigation. She notes that the book contains "important info that's nowhere else" that she uncovered while interviewing witnesses that included Juan Romero, the busboy whose life was forever scarred by the fact he was seen worldwide holding Robert Kennedy as he lay dying in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

Pease also spoke with actor/filmmaker Emilio Estevez, who created the 2006 film

Bobby about the impact RFK's assassination had on a broad array of fictional Ambassador staff and guests. During a visit to the film's set,

Estevez introduced her to a person who claimed to have witnessed a different person actually shooting Robert Kennedy.

"At first I was skeptical because so many say they were there, but this guy was really there," says Pease. "He must have seen a lookalike of Sirhan, because he swears it was Sirhan but also completely got the color of his clothing wrong and saw Sirhan in a place he could not have been.

The guy he saw going right up to Kennedy's head was wearing a white busboy uniform, but Sirhan wasn't wearing one and never got that close."

Pease notes that RFK was shot four times from behind,

from about an inch away, while Sirhan was three feet in front of him. She finds it noteworthy that the one of the private security guards that night

worked for Robert Maheu, the man the CIA contacted to run its assassination plots against Castro at the time Maheu ran Howard Hughes' company out of the Mob mecca of Las Vegas.

She subscribes to the widely held theory that Sirhan was under hypnosis, an idea that was investigated in-depth by this reporter in the

Weekly in 2008 (

pasadenaweekly.com/2008/09/25/a-tale-of-two-sirhans/). In that article, Sirhan's family and legal team noted that the then-Pasadena City College student had strangely developed an affinity for attending hypnotists' performances in the weeks leading up to the Kennedy assassination.

"I started going to hypnosis shows to see what effect it had on the hypnotized, and was able to sit next to a volunteer, whom I saw before and after the show too," says Pease. "After the crowd had cleared and the hypnotist had left the area, she was still standing and looking at a piece of play money that, during the show, she had been hypnotized to believe was $25,000. She was distressed holding obvious play money, and she was distraught saying she had to give it back. She literally could not see that it was not a check but simply play money."

Pease shoots down numerous other aspects of the official take on RFK's murder, including the number of gunshots reported and the numerous improprieties in how the criminalist for the LAPD handled the evidence. She also notes that numerous people who participated in the official take on the assassination went on to gain major promotions to better government positions.

"It's easier for the police to prosecute the guy they have than the conspiracy they don't have the details on," says Pease. "The initial announcement among police to avoid comments that could lead to conspiracy theories might have been innocent, but that's why I titled my book

A Lie Too Big to Fail.

"

Once you tell the first lie, you have to keep telling lies to keep the first lie intact," Pease continues. "At some point, the lie became too big to fail. Here's the thing: If they framed an innocent man and didn't get the rest of the conspirators, that makes the LAPD look so bad. They didn't invent this cover-up for the Sirhan case. They already had procedures in place for convicting people when evidence was nonexistent."

A Lie Too Big To Fail may be purchased at

amazon.com.

Comment: Neal Colgrass at newser.com writes: