But now archaeologists have found conclusive proof that nuns were involved in producing sacred texts.

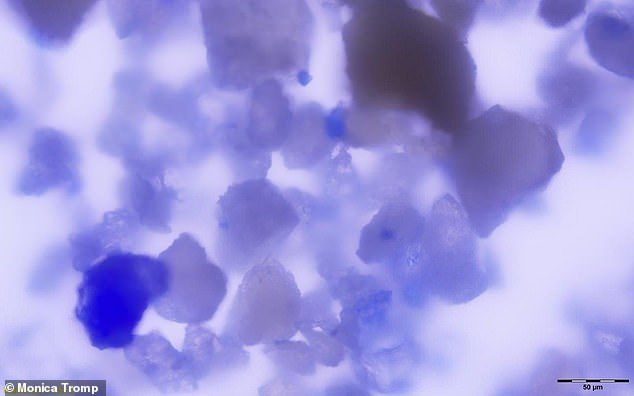

Tests on the teeth of a middle-aged female skeleton at a cemetery attached to a medieval nunnery in Germany showed flecks of a rare blue pigment on her teeth.

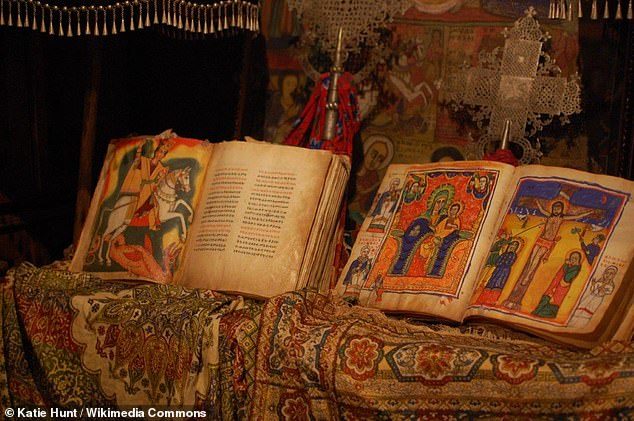

Scientific detective work reveals that the blue colour - ultramarine, made from the semi-precious stone lapis lazuli - indicates she must have been involved in painting the holy books, and licked the end of her paintbrush when using the rare pigment.

The discovery shows women were producing art in a time when it was considered largely the preserve of men.

Lapis lazuli was costly as it was produced from a single mine in Afghanistan.

In medieval times it was just as expensive as gold and there were few other blue pigments at artists' disposal.

The use of ultramarine was reserved, along with gold and silver, for the most luxurious manuscripts and the most skilled artists.

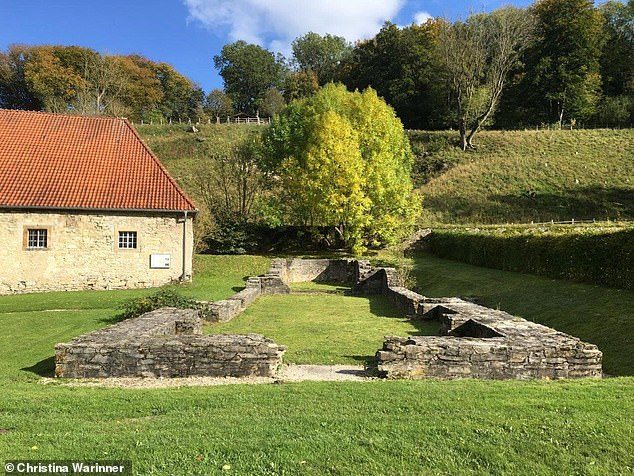

In a study published in Science Advances, a team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of York discovered a woman had been buried at the convent at around 1100AD.

The only unusual feature about her were the blue particles found in her teeth, the researchers said.

No books were preserved from the nunnery at Dalheim, in Germany.

She added: 'We examined many scenarios for how this mineral could have become embedded in the calculus on this woman's teeth.

Fellow author Monica Tromp of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History said: 'Based on the distribution of the pigment in her mouth, we concluded that the most likely scenario was that she was herself painting with the pigment and licking the end of the brush while painting.'

The institute's Christina Warinner, a senior author on the paper, added: 'This woman's story could have remained hidden forever without the use of these techniques.

'It makes me wonder how many other artists we might find in medieval cemeteries - if we only look.'

in general, everybody had to pull their part, outward or inward pointing genitals alike, (as well as the others)