The ancient warrior was buried in fur and lay on a wooden 'bed' in his burial chamber at a remote Altai Mountains site near the modern day village of Kokorya, some 314 kilometres south of regional capital Gorno-Altaisk. Next to the warrior was placed his weaponry.

His bow in its heyday was some two metres in length; alongside its remnants were half a dozen well-preserved arrow shafts made of birch.

They were painted in black and white - so he knew which one to pull from the fur-lined quiver for each prey.

The arrows originally had iron tips.

Hun hunters deployed these weapons to confuse their prey forcing them into the open, when they could be shot with other arrows.

Deer would stop when they heard the whistling, making them easy targets.

Squirrels jumped lower in their branches becoming more exposed, or leapt between trees - so going into the open.

Archeologist Dr Alexander Ebel, from Gorno-Altaisk State University, conducted an experiment to make a copy of the arrow whistle.

It didn't work.

Yet a study by Novosibirsk archeologist Yury Khudyakov suggests these arrows did whistle, a phenomenon described in ancient Chinese literature.

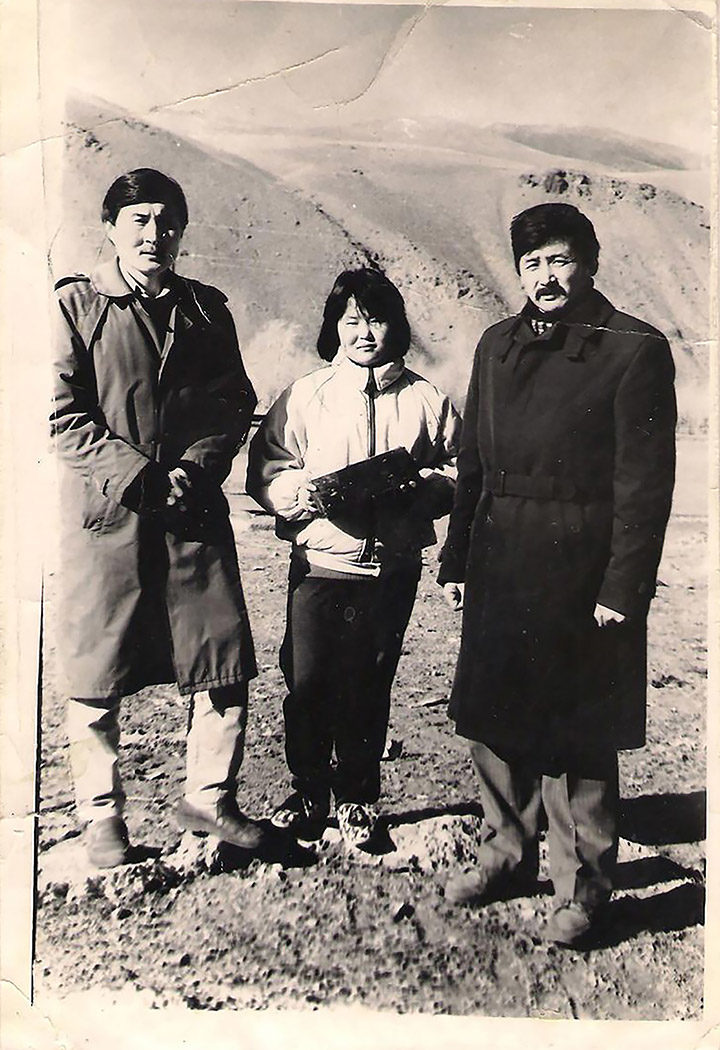

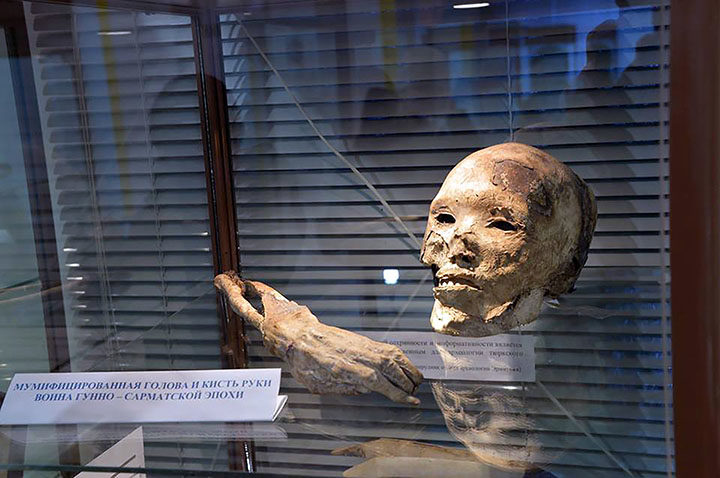

The mummified warrior was unearthed in 1993 at the remote at Kam-Tytugem settlement.

Alena Kypchakova, then 12, stumbled across the remains when she was set to work haymaking.

She has since taken over from her father running the local museum in Kokorya.

'I saw a pile of stones,' she recalled. 'It turned out that the grotto had collapsed. I found a hole between the stones, a way to get inside - and there was a grave.

'I don't remember it too well, but I know I was not scared.'

A local historian came and inspected the find.

Before long eminent scientist Boris Kadikov from the Hermitage arrived too; he and a researcher spent three days with the find.

Attempts to persuade her father to surrender the find to faraway museums - notably the Hermitage - all failed.

'I remember Boris Kadikov told my father: 'Keep this head, do not give it to anybody, and one day your museum will be famous.'

This moment has come.

Comment: See also: