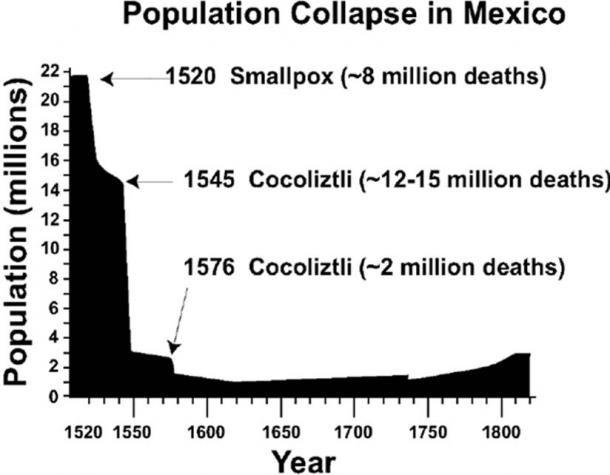

The journal Nature reports that the native population of Mexico was around 25 million when Hernando Cortés arrived in 1519, but just a century later there were only 1 million people remaining. The primary cause for this dramatic decrease in population was apparently two major outbreaks of cocoliztli, one in 1545 and the other in 1576. As Dr. Acuna-Soto, a professor of epidemiology on the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University (UNAM) of Mexico wrote "In absolute and relative terms the 1545 epidemic was one of the worst demographic catastrophes in human history, approaching even the Black Death of bubonic plague."

There has been a great deal of debate over what cocoliztli was, though small pox, measles, a viral hemorrhagic fever, and typhus have all been suggested to have been behind the epidemics.

In Acuna-Soto's article, published in The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2000, he wrote that his team's research showed that the illness:

"was characterized by an acute onset of fever, vertigo, and severe headache, followed by bleeding from the nose, ears and mouth; it was accompanied by jaundice and severe abdominal and thoracic pain as well as acute neurological manifestations. The disease lasted three to four days, was highly lethal, and attacked mainly the native population, leaving the Spanish population almost untouched."But now, a team led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany have discovered a strain of Salmonella enterica known as Paratyphi C in the DNA from the teeth of 29 people buried in an early contact era epidemic cemetery at Teposcolula-Yucundaa, Oaxaca in southern Mexico. Ewen Calloway's article in Nature describes the main symptom and possible effects of this bacterium, it "causes enteric fever, a typhus-like illness [...] If left untreated, it kills 10-15% of infected people."

The study, published in bioRxiv, suggests that the Salmonella Paratyphi C may have arrived in Mexico from Europe along with the "variety of plants, animals, cultures, technologies [...that] accompanied the movement of people from the Old World to the New World immediately following initial contact, in a process commonly known as the "Columbian exchange.""

Read the remainder of the article here.

Alicia McDermott has degrees in Anthropology, International Development Studies, and Psychology. She is a Canadian who resides in Ecuador. Traveling throughout Bolivia and Peru, as well as all-over Ecuador, Alicia has increased her knowledge of Pre-Colombian sites as well as learning more about modern Andean cultures and fine-tuning her Spanish skills. She has worked in various fields such as education, tourism, and anthropology. Ever since she was a child Alicia has had a passion for writing and she has written various essays about Latin American social issues and archaeological sites. Her hobbies include hatha yoga, crocheting, baking, reading and writing.

Comment: Interesting that both the Cocoliztli epidemics of 1545 and 1576 coincide with cometary observations. Such cometary bombardments have been associated with numerous plagues and civilization collapses: See also: