Comment: The following article from 2012 provides a glimpse into the paranoid mind of a senior CIA operative. James Jesus Angleton was not a one-off. They may not all have been as paranoid as this one, but they were (and still are) probably all just as pathological...

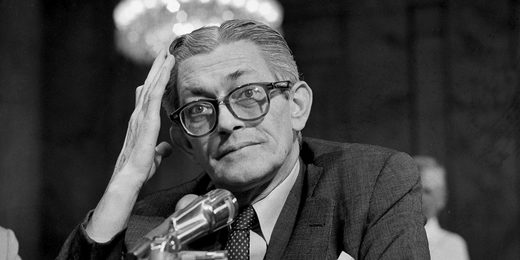

As chief of CIA counterintelligence, James Angleton famously described his world as a "wilderness of mirrors."

This week, that wilderness will be revisited at a joint conference on Angleton's legacy held jointly by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Georgetown University's Center for Security Studies.

As the author of three books on the CIA, I was honored to be asked to participate as a speaker. But my first thought on hearing about the conference was: Why waste time on Angleton?

Today, no one in the CIA or FBI considers Angleton, who died in 1987, to have been anything other than a paranoid conspiracy theorist who paralyzed CIA intelligence operations against the Soviet Union and never caught a spy.

Upon further reflection, however, I recognized how important the conference is. That's because defenders of Angleton continue to confuse the public about Angleton's legacy and his approach.

When it comes to catching spies, no one rivals John L. Martin, a lawyer and former FBI agent who headed Justice Department espionage prosecutions for nearly 25 years. Martin supervised the prosecution of 76 spies. They included John A. Walker Jr., a Navy warrant officer; Jonathan J. Pollard, a spy for Israel; Ronald Pelton, a former NSA employee; and Aldrich Ames, a CIA officer. Only one of the prosecutions resulted in an acquittal.

"Angleton fostered the misconception that counterintelligence officers need to be a different breed - suspicious to the point of paranoia," Martin told me for my book The Bureau: The Secret History of the FBI.

"Often, this outlook is referred to as a counterintelligence mentality," Martin says. "This is pure malarkey. People who catch spies need to be no more and no less suspicious than people who catch murderers, bank robbers, or white collar criminals. To be effective, any professional investigator must bring a balanced approach."

Angleton called counterintelligence a "wilderness of mirrors" and saw catching spies as a game. Martin saw it as deadly serious business that relies on hard evidence, not conspiracy theories. Under Martin's watch, no case was overturned on appeal, and no one ever accused him of acting unethically.

"I'm a firm believer in giving them their full constitutional rights and then sending them to jail for a lifetime," Martin would say.

Angleton once met with Martin at the Justice Department and wanted him to point out material he thought would be in trial transcripts to confirm his theory that Christopher J. Boyce, a 23-year-old TRW employee who was caught for selling material to the Soviets in Mexico City, and his childhood friend Andrew Daulton Lee, were really being directed by a Soviet mastermind.

Their exploits were portrayed in the book and movie The Falcon and the Snowman.

"Boyce and Lee wanted money to get the drugs necessary to feed their habits," Martin says. "But Angleton thought the public trial transcripts would show they were part of a Soviet-directed plot. Angleton was a nut case who should not have been employed by any agency, let alone the CIA."

A thin man with a sallow complexion, James Jesus Angleton graduated from Yale. He bred orchids, wore a black homburg, and drank heavily.

Angleton frequented La Niçoise in Georgetown, where he drank I.W. Harper bourbon with a few cubes of ice, chain-smoked Virginia Slims, and often ordered the mussels. He insisted that the chef remove any white-colored mussels. He wanted only those with orange-colored flesh, Michael Bigotti, who waited on him and became the restaurant's manager, told my wife Pamela Kessler for her book Undercover Washington: Where Famous Spies Lived, Worked and Loved.

Angleton propagated the theory that all Soviet defectors were double agents sent to uncover American secrets. His paranoid outlook and his tendency to label as spies those who disagreed with him so intimidated the agency that recruitment of CIA Soviet bloc assets stopped.

Referring to two early Soviet defectors, William F. Donnelly, a CIA case officer who became chief of internal Soviet and East European Operations, told me that because of Angleton, "We were blind after [Oleg] Penkovsky and [Pyotr] Popov were gone."

Angleton accused everyone from the Paris station chief to CIA directors of being moles. When he became director of Central Intelligence, James Schlesinger asked Sam Hoskinson, an assistant, to meet with Angleton and find out what he was doing.

Hoskinson found Angleton "seated behind his desk, blinds drawn, a single desk light on," according to From the Shadows, a book by Robert M. Gates, who later became DCI.

As Angleton chain smoked, he wove Soviet conspiracy theories, finally concluding that Schlesinger was one of "them." When Hoskinson told Angleton that he would have to tell Schlesinger what he had said, Angleton glared at him.

"Well, then, you must be one of them, too," Angleton said.

In his book Spy Handler, former KGB officer Victor Cherkashin said Angleton "swallowed" a claim made by KGB defector Anatoly Golytsin that every defector after him would be a double agent.

"Golytsin made that claim because he'd soon run out of secrets to tell the Americans and wanted to enhance his importance," Cherkashin wrote.

"Angleton ruined many careers and all but paralyzed the agency because the paranoia he stoked made recruiting agents - highly risky under any circumstances - nearly impossible," Cherkashin said.

"Angleton had been mesmerized by Golytsin," said Rolfe Kingsley, who headed the CIA's Soviet Division. "Angleton saw a mole under every chair. If you had something successful, he said it was a Soviet throwaway. It couldn't possibly be true. Angleton was a brilliant guy. But he was a menace."

By talking in riddles, Angleton managed to convey the impression that he knew far more than anyone else.

"I spoke to Angleton six times," said Angus Thuermer, a longtime CIA spokesman. "I never quite understood what he had said."

Angleton's fixation with orchids - which he proudly showed me through clouds of cigarette smoke at his northern Virginia home - enhanced his reputation as a quirky genius.

I met with him in April 1987, a month before he died of lung cancer. I brought up the case of Karl Koecher. All along, in Koecher there really had been a mole in the CIA, but it was the FBI - not Angleton - who caught him. While a high-level translator at the CIA, Koecher was working for the Czech Intelligence Service, an arm of the KGB.

As noted in my book The Secrets of the FBI, Koecher and his gorgeous wife Hana attended sex parties and orgies in part to obtain classified information from others who attended from the CIA, White House, and Pentagon.

Koecher compromised Aleksandr D. Ogorodnik, a high-ranking Soviet diplomat then working for the CIA. Ogordnik's information about the deliberations of Soviet leaders was so important that it was circulated directly to U.S. presidents. Yet Angleton never had a clue about this devastating spy case within his own agency.

I told Angleton that with my wife Pam, I had just spent five days interviewing Koecher and Hana in Prague after they were traded. The spy catcher showed no interest. For Angleton, it had all been a game: Koecher was not the mole he had been seeking. Therefore, he could care less.

Angleton was chief of counterintelligence for more than 20 years. Fear was the secret to his longevity. Angleton kept huge files with names of CIA officers who had come under suspicion based on his amateurish theories. Anyone who called his bluff could become a target.

Angleton would continue to poison the air until William E. Colby, as director of Central Intelligence, finally fired him in 1974.

"Those who think Angleton's paranoid mentality, intimidating tactics, and dishonest charges against innocent CIA officers were admirable risk a return to the disastrous days when the FBI and CIA trampled on Americans' rights and overlooked real spies," Martin says. "The revisionists are dangerously inviting history to be repeated."

About the author

Ronald Kessler is chief Washington correspondent of Newsmax.com. He is the New York Times bestselling author of books on the Secret Service, FBI, and CIA.

Angleton's fixation with orchids - Strangely, in the 1800's orchids were discovered, it was a rare species of flowering plant. And what is called the orchid wars began, vast amounts of monies were exchanged to obtain the plant (some questioned if the plant had hallucinogenic properties). If fact there was a movie made about the hallucinogenic properties of the Ghost Orchid, it's called Adaptation, true or not I don't know, the author of the non fiction book claims it was all made up for the movie from my understanding.

About the Orchid wars, comes across more like a drug war to me.

[Link]

But there is evidence of saffron being used for hallucinogenic properties in the UK. There was a paper written a few years back by an academic, (unfortunately the link is dead, and the last time I looked it up to obtain a copy it was around fifty pounds sterling) It concerns a group of nuns in Saffron Walden (hence the name) that purchased vast amounts of saffron, far in excess of use for domestic purposes, it was conjectured that they used the saffron to bring them closer to god. Nuff of that just some trivia.

Regarding Angleton himself, he was considered a "genius" of what! Psycho-pathological deception, well by comparison, today's offering from the CIA, they are brain dead, it's the same old mantra, the same old MO.

Seems to me they are using the same old manual, guaranteed to bring success, really!

But from where I sit, the same old shit no longer works anymore, people are waking up and recognizing the patterns, the lies and deceptions as co-intelpro operations, the emperor is slowing losing any vestiges of clothing he had, and personally for me I hope it continues until he is naked before a very discerning public, and all I can say, is god help them.