© Zupancich, A. et al. / Scientific Reports

, road workers detonated a controlled explosive to remove a large limestone boulder blocking a planned roadway outside of Tel Aviv in Israel. Soon after the dust settled, it became clear that the road would need to be rerouted.

The workers had stumbled upon a vast cave, one that had been sealed off for more than 200,000 years! For the researchers who soon began exploring the cave's expansive interior, it was the find of a lifetime.

Now called Qesem Cave, the site has delivered a number of discoveries that live up to its explosive origin. Archaeologists

found a 300,000-year-old fireplace, along with tortoise shells that

showed signs of burning. Apparently, whoever live there had a taste for roast tortoise.

Exactly who lived there remains a mystery, however. While archaeologists have uncovered a

handful of hominin teeth, they still aren't sure which species they belong to. It could be

Homo erectus,

Homo neanderthalensis, or it might even be an entirely new species.

"We don't know which type of human lived here," Ron Barkai, an archaeologist at Tel Aviv University,

told Ynet News. "We know that they acted differently than everyone else who lived in this area before them."

Whoever inhabited Qesem many eons ago, a

study recently published in

Scientific Reports reveals that they were advanced tool-users.

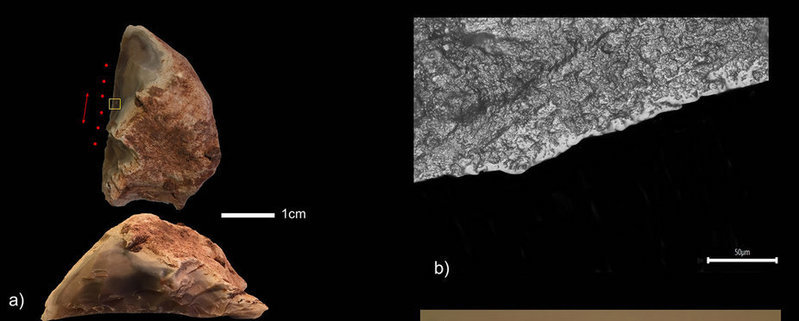

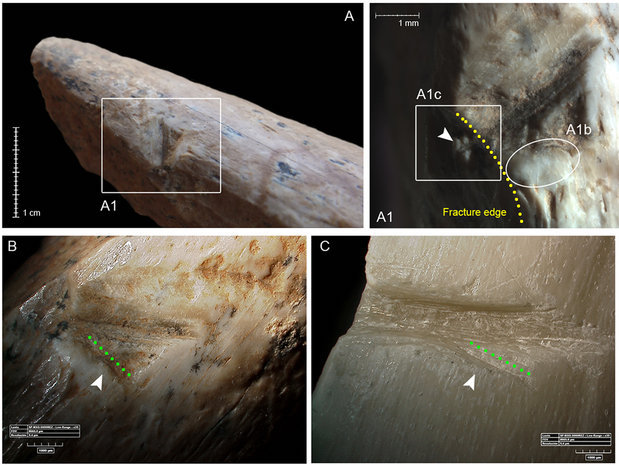

A team of Archaeologists led by Barkai and his colleagues Avi Gopher and Andrea Zupancich uncovered two sharpened flint tools (pictured above), as well as a deer bone with distinct saw marks (pictured below). The artifacts are between 300,000 and 420,0000 years old.

© Zupancich, A. et al. / Scientific Reports

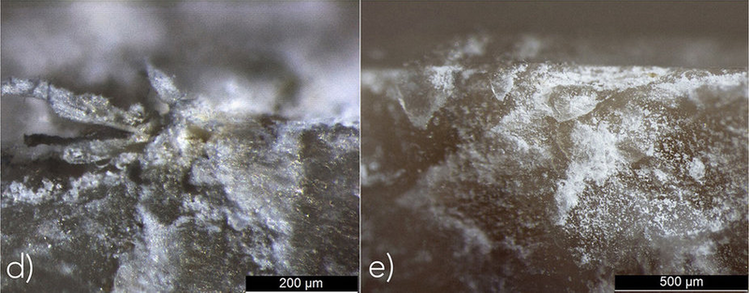

While most observers would simply be satisfied with putting two and two together, the researchers wanted to be sure that the tools were actually used on the bones, and that the marks didn't simply result from gnawing or butchering. Rigorous examination revealed clear bone residues on the flint tools. (See image below.) The researchers also observed signs that the marks were created after the bone was broken and defleshed.

© Zupancich, A. et al. / Scientific Reports

"The results of this study allow us to argue that at Qesem Cave, hominins were bringing selected body parts of hunted game to the cave and, after the meat, fat, and marrow were consumed, they occasionally used the discarded animal bones for non-dietary purposes," the researchers write.

Tool use

dates back at least 2.5 million years, but this may be one of the earliest examples of hominins modifying and utilizing tools for a purpose other than eating or hunting for food.

"The data presented here represents an innovative behaviour, practised between 420 and 300 kya, possibly the oldest evidence related to intentional non-dietary modification of bone through the use of specific stone tools," the researchers say.

Coupled with past findings, the present study clearly shows that Qesem Cave was a hub of activity for intelligent hominins. The last - and greatest - mystery left to be solved is to find out exactly who those hominins were.

Source: Zupancich, A. et al. Early evidence of stone tool use in bone working activities at Qesem Cave, Israel.

Sci. Rep. 6, 37686; doi:

10.1038/srep37686 (2016).

Ross Pomeroy is a little uncertain when he states "Exactly who lived there remains a mystery, however."

Well Ross, I know who lived there; Palestinians lived there Ross.